(First published on time.com and used with the written permission of the author and publication of first instance.)

By Ed Grant

Now that the superslick, pastel-colored, amply-budgeted, big-screen rendition of “Charlie’s Angels” has been released, the time has come to re-evaluate the television series that inspired the movie, and set off the gals-with-big-guns-and-even-bigger-hair trend for a short time in the late ’70s. Let’s abandon for a second the sentimental memories that have now transformed the show into a top-notch action series, and remember “Charlie’s Angels” as it truly was: a pathetically awful bit of TV. Its emphasis on fine bodies, scenic locales, and (lest it be forgotten) perfect hair didn’t elevate it to “so bad it’s good” status (a la “Cop Rock”); the show was, to be blunt, a big bore.

Admittedly, there were some blessedly kitschy episodes: the disco-intrigue show that guest-starred future schlock-erotic moviemaker Zalman King (The Red Shoe Diaries); the women’s prison episode costarring low-budget icons Shirley Stoler and Sally Kirkland; an earlier babes-behind-bars outing in which a pre-“Love Boat” Lauren Tewes implores the Angels to rescue her sister from a harsh prison run by Warhol/Corman veteran Mary Woronov—a prison also inhabited by future Oscar winner Kim Basinger. And the series featured not only the requisite ’70s guest appearance by Sammy Davis Jr. (playing twins!), but also a dramatic turn (if you can call it that) by Dean Martin as a gambler who falls in love with Sabrina Duncan (Kate Jackson).

Aside from this handful of gems (sprinkled throughout the show’s five seasons), “Charlie’s Angels” fell flat as trash TV. The reason? Successful exploitative entertainment is created by people who are either entirely honest about what they’re doing (in the unrepentently sleazy manner of professional wrestling) or blissfully unaware of how bizarre their creation actually is (the patron saint of this sort of misguided brilliance being the legendary Edward D. Wood Jr.). “Charlie’s Angels” had a sterile approach that contrasted sharply with its reputation as the foremost example of “jiggle TV.” Having been a teenager during that period, I can assure you that sexier situations cropped up in any random installment of the “Battle of the Network Stars” (to wit: Heathers Locklear and Thomas locked in a carnival-style dunk tank wearing flimsy swimsuits).

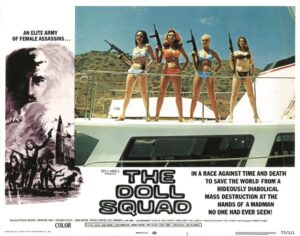

But while Aaron Spelling was busy dispensing tedium on TV in the 1970s, certain low-budget filmmakers were ensuring that drive-ins and grindhouses contained some genuine “jiggle,” producing sincerely strange entertainment on a regular basis. Such a man was Ted Mikels, who continues to ply his trade today, turning out ultra-low-budgeted features with eye-catching titles and very unusual behavior. In 1973, Mikels made The Doll Squad, considered by many to be the inspiration for “Charlie’s Angels,” as it contains a crack team of glamorous female operatives, a well-connected male boss, and a “smart” team leader named Sabrina.

Mikels has never harped on the connection between the two (first spotted by cult-movie fanatics); in fact, he goes so far as to downplay it in interviews. When I spoke to him at the Chiller Theatre convention in the late 1990s, he amiably stated that “I never once thought of pursuing litigation… I can sit down and dream up new stories like that…As fast as my fingers can snap, I can give you a premise for a new story just like it. There are a lot of people who have ideas…maybe it just so happened that the powers-that-be [behind “Charlie’s Angels”] had seen [The Doll Squad] or its script.”

Mikels’ movie may not have been the source for “Charlie’s Angels,” but it does have its own special charms, including a catchy, typically ’70s horn-driven musical soundtrack and a supporting turn by the ever-vivacious Tura Satana (star of Russ Meyer’s Faster! Pussycat! Kill! Kill!). The plot finds a group of six, not three, female agents invading the island stronghold of ex-government agent Eamon O’Reilly (swarthy Michael Ansara, best known for working on ex-wife Barbara Eden’s “I Dream of Jeannie”). O’Reilly intends to use bubonic plague to conquer the world—unless he can be stopped by our bodysuit-clad, machine-gun-totin’ heroines (who are, by the way, quite nicely coiffed as well).

The most surprising thing about The Doll Squad is that this flashy little number is by far the least of Ted Mikels’ efforts of the period. The plotline is doted on at length (always a mistake in low-budget espionage dramas with shapely female leads), and when the all-out action sequences finally do arrive, the visuals are incredibly dark. This is most likely due to the fact that much of the film’s closing action was shot in one night, on which Ted had the temporary loan of a real machine gun (thus, the actresses are actually blasting away with the same weapon).

Ted’s most unusual, and infinitely rewatchable, movies are a trio of no-budget wonders that belong in the video collection of any serious student of outre cinema. The Astro Zombies (1968), coscripted by “M*A*S*H”’s Wayne Rogers, stars John Carradine as—natch—a mad scientist, and Tura Satana as a Dragon Lady criminal mastermind. Tura is one of many individuals looking to snatch Carradine’s secret of bringing cadavers back to life with solar energy (don’t ask). The horrendous creatures he resurrects are incarnated by stunt men wearing dimestore skull masks, so a good time is had by all. The Corpse Grinders, Ted’s best-known horror outing (which outgrossed several Hollywood studio features in 1970), concerns a failing cat food company that discovers a new ingredient for its product—human flesh.

This fanboy’s favorite Mikels’ opus, however, is the redoubtable Ten Violent Women (1979). Ted’s most loosely-plotted picture (loose scripting being a supreme virtue in exploitation cinema), Women concerns a group of female miners (!) whose jewel heists and drug deals land them in prison. Once there, we witness the requisite staples of the women-in-prison genre (making this the most lurid film Mikels ever made) as the girls engage in shower catfights, evade the lustful warden,and endure a bizarre paint-can-on-the-head torture session. They eventually escape to safety—and the waiting arms of Arab oil sheiks (again, don’t ask).

Mikels’ movies always have a preponderance of female leads. This is not only because Ted is fascinated by the ladies—“I’ve always had a deep, deep feeling about females,” he notes—but because he had a number of them living with him for a period of about a dozen years in the 1970s and ’80s. Dubbed Castle Ladies, for Ted’s former castle-like Glendale, CA. residence, the women were aspiring filmmakers who lived with Ted and served as the crew–and cast–of his films. “I had this big place, and I thought, well, I could bring them in and help them improve their life…It was mostly those who had expressed an interest in making film that would come to the castle, and I would teach them.” Ted is reticent to talk about his personal involvement with the 60-70 women who lived in his home during this period, but will admit that “they did have a commitment to me. If they lived with me and I took care of them and cooked for them and paid the bills and all that, they were not to have involvements with other men…They didn’t owe me anything, they didn’t have to sleep in my room, my bed….”

The Castle Lady period of Ted’s life is now over—although it does loom large in his legend (when traveling in public, the women referred to themselves as Ted’s “wives”). But Ted has kept women in the forefront of his productions. The latest manifestation of this femme-mania is a wild outing titled Apartheid Slave Women’s Justice. Shot on videotape, the feature is a race-relations allegory about a kangaroo court of black South African women who capture and try their former “master,” played by Mikels. The women deliver wildly melodramatic speeches as they kick the hell out of Ted, frequently stepping on him in high heels; the kicks are accompanied by a rather amusing videogame-like “doink! doink!” sound that seems to grow on one as the video progresses. The proceedings are sporadically interrupted by exterior shots of African dancers, a rainswept street, and unexplained scenes of black people eating—and then it’s back to Ted’s beating and more speeches.

Mikels insists that he has always worked clean, not wanting to leave his family with “a legacy of distaste”; thus, even movies with wonderfully lurid titles like Blood Orgy of the She Demons are essentially G-rated. Apartheid doesn’t depart too much from this philosophy—except for the fact that a good deal of the time the proceedings resemble a trample-fetish video. However, in an era when Hollywood entertainment— Charlie’s Angels included—is remarkably predictable, Mikels’ work still comes as a cold slap in the face. Apartheid’s oddly discordant tone, jarring juxtapositions, and the fact it features long stretches of a cult moviemaker laying on what is presumably the floor of his own house being kicked (“doink! doink!”) by actresses who also worked in his crew, make it a highly recommended item that’s worthy of cult adoration and academic study (and possible Freudian analysis) in “Incredibly Strange” pop culture classes of the future. Take that, Aaron Spelling…

c. 2000, 2013 Ed Grant