677.) One of the most imitated contemporary cinematographers is featured in an interview on this week’s vintage episode. Christopher Doyle — the crafter of exquisite imagery for Funhouse favorite Wong-Kar Wai and a man whose work on low-budget Asian features has spawned countless arthouse knockoffs, mainstream attempts at arthouse chic (yeah, you, Sofia Coppola), commercials, and even music videos — is the gent in question and we’re presenting the more civilized portions of a rambunctious talk he had with our friend, Asian cinema specialist extraordinaire Art Black, a few months back. Art caught Doyle after a full day of promotion for the Thai film Last Life in the Universe — and after quite a few beers (as Doyle himself notes on the acknowledgments of his only, nearly plotless, directorial effort, “Beer is Life!”). The result was a fascinating talk with a very talented artist who wasn’t really into analyzing and dissecting his work…except when it sorta struck his fancy. Art’s talk covers his time with the great Wong Kar-Wai (the two have collaborated from Days of Being Wild to the current masterful pastiche of romance, science fiction, and heartsickness, 2046); his disdain for those who imitate his visual style; his desire to work exclusively with friends on projects he really has a passion for (his quartet of American big-budget projects, including Van Sant’s Psycho clone, are aberrations in his filmography); and his appearances as an actor in his friends’ films.

678.) This week’s episode is a vintage Deceased Artiste tribute episode: We never stop loving pop-culture icons in the Funhouse, so we’re fine with doing our Deceased Artiste tributes some time after the subject has departed this mortal coil—and everyone has moved on to the next trendy topic. Thus my tribute to the “King of Late Night,” Johnny Carson, offers a range of clips and a discussion of his randier side, an aspect most of the softsoap tributes veered away from. The reason this side of his humor was left out of the tributes is obvious: the first ten years of his run on The Tonight Show is lost to posterity (and that’s the time he was a racy little devil), and any discussion of his propensity for smokin’, drinkin’, racist, and leerin’ big-boob jokes on the show would’ve clashed with the folksier image he cultivated as his hair turned to silver. In any case, he was the pre-eminent masterful late-night host, and as such deserves to have a full Deceased Artiste episode. We start out with a racy “lightning round” from the more “adult” Goodson-Todman show, Password, then move on to the hard-smoking 1965 youthful Johnny trading quips with the ever-caustic and delightful Henry Morgan. A short sidebar into Johnny’s primetime work, and we’re back to Tonight with clips from the 10th anniversary show from 1972 (watch former Rat Packer “The Bish” do the “Sammy Maudlin” mutual-admiration thing for real, Jack Benny smoke a big-ass stogie, and Funhouse deity Jerry Lewis get insulted by nice-guy Johnny).

679.) The Consumer Guide department offers up two filmmakers who provide dream imagery as part of their practice. First up, a review of the Criterion Collection release of Jane Campion’s Sweetie, one of my favorite “discoveries” of the late 1980s. Campion’s tale of sibling rivalry in a dysfunctional family is distinguished by its wonderfully “off” compositions, which add a mildly surreal edge to the most normal-looking suburban settings. After exploring the supplements found on the Sweetie disc, we enter the world of Jacques Rivette. It’s very hard to summarize the work of the least known of the French New Wave filmmakers, primarily because his films are characteristically very long, most running a minimum of 150 mins (the longest ever clocking in at over 12 hours). In conjunction with the current comprehensive festival of his work running at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, I discuss the themes and techniques that have permeated his work for 45 years now, including his love of ensemble casts, a focus on communities of theatrical folk, and the introduction of conspiracies/plots/“master plans” into his narratives. A select group of clips illustrate the discussion (Rivette’s work is notoriously hard to excerpt), as we move from the very first feature (the wonderfully existential bohos-in-crisis paranoia thriller Paris Belongs to Us, 1960) to a 1990s work that is, like many of his films, currently out of distribution over here, the experimental “musical” Haut Bas Fragile (Up Down Fragile, 1995), in which the characters sing and dance in the manner of folks who’ve seen too many films in which people suddenly begin to, well, sing and dance.

680.) Sales of TV-on-DVD remain steady, and we in the Funhouse are always eager to tout the better products showing up on (some) chain-store shelves. This week, the “Consumer Guide” focuses on three boxes, each of which contains untold wonder and a round-trip ticket to the not-so-recent past. First, we tackle the most wholesome couple that ran a talk show in the 1970s, Donny and Marie. In the wake of the married couples and multi-racial singing combos that quibbled on their eponymous variety shows, D&M were a family-friendly duo (ripe for odder fantasies in the stranger, or ripely pubescent, minds in the audience) who spearheaded the slickest lil program of the latter half of the decade. We turn from Donny and Marie box to the latest SCTV offering, The Best of the Early Years. While I disgree with the box’s title, the contents are simply delightful and seem as fresh today as when the show was in its first syndicated run in ’77-81. This collection stresses the great contribution made by the “new” cast member in the third season, Rick Moranis, who helped jumpstart the show and prepare it for its eventual NBC glory phase. Last up is the Hollywood Greats collection of The Dick Cavett Show. About a third of the box appeared recently on Turner Classic Movies, but the other two-thirds is equally as brilliant, and will once again make ya wonder, “how the hell could TV have been so smart back then, and so dumb now?” Included in the clip-montage are scenes from the episodes featuring Brando, Welles, Astaire, Groucho, and recent Deceased Artiste emeritus Robert Altman.

681.) We love to dote on the variety and talk shows of old in the Funhouse, and so this week it’s Consumer Guide time again, and the focus is on comedy. At the top of the show I review a new collection of George Burns’ TV specials that demonstrates the full range of Burns’ remarkably mellow standup (he remained a straight man, even when alone on stage) and the admiration he received as a senior statesman of comedy from his peers and successors. The nine specials included in the box offer a wondrous cross-section of late ’70s/early ’80s guest stars, from which I’ve picked just a scant few (regular viewers know the impulse to show Ann-Margret — especially during her sexy, tousle-haired, she-might-have-a-nervous-breakdown-at-any-second mid-career incarnation — will never, ever be resisted). We move from Gracie’s perennial straight guy to the king of late night, reviewing the latest Johnny Carson compilation, an uneven but entertaining compilation of clips from Tonight that includes a few choice nuggets from the less wholesome and folksy Johnny (and his delightful bete noir, the Rickles). Last is the featured disc of the eve, Soupy Sales: In Living Black and White, a single-DVD collection of sketches and blackouts from the Soup’s mid-’60s Metromedia program. You get the expected joys — White Fang, Black Tooth, and the most expressive hands in show biz, belonging to “the Nut in the Door” (Frank Nastasi) — but the coup de grace for me are the segments in which Pookie lip-synchs to some dynamite pop and Soup just “listens to the radio” for a few minutes (the sort of “filler” that is bliss incarnate).

682.) Vintage episode time: From the heart of NYC to the wilds of Alaska, our “consumer guide” adventure this week centers around two colorful and unique German gentlemen. The first is Klaus Nomi, whose praises are sung in the new DVD release, The Nomi Song. I focus on the DVD supplements in this review, featuring a portion of a “East Village Slide Show” that didn’t make it into the film but should produce some fond memories for those who remember the prehistoric days when chainstores had no place on the bohemian landscape. The film itself is an entertaining look back at the most singular personality to emerge from the “new wave” music scene; the final sequences prove that even the most open-minded hipsters close their minds for real when confronted by a thought-to-be-contagious virus (Nomi died of AIDS in 1983). The feature presentation on this show is a short chat I had with Werner Herzog, in conjunction with the opening of his new film Grizzly Man. Herzog’s reputation as a visionary filmmaker was secured some thirty years ago, but he has continued to venture to the farthest corners of the globe to create a series of highly personal documentaries in which he chronicles the lives of remote groups (be they deaf, mute, and blind, or just tribesmen who dress very bizarrely) and fearless individuals, many of whom are possessed of a very fine madness indeed (the central figure in Grizzly being the latest in a long line of his compelling madmen). Herzog was in quite a jovial mood when I encountered him, although a single mention of a given sequence in one of his films can turn him into the intensely sincere, uncommonly dedicated individual I expected him to be.

683.) The first part of our three-episode Deceased Artiste tribute to the late, great Robert Altman starts off with commentary and context from yours truly, exploring the legacy of this brilliantly innovative filmmaker. We survey his earliest works as a screenwriter and director with clips from, and discussion of, three rarely seen early works: the aptly titled Corn’s-a-Poppin’ (1951), a no-budget regional effort that resembles the “Scalli” films featuring Ed Wood actor Timothy Farrell (two people in a room, one behind desk, talking, hopefully boom mics catch the sound); the B-budget noir Bodyguard with real-life tough yegg Lawrence Tierney; and Altman’s first directorial effort, the j.d. yarn The Delinquents (watch “Billy Jack” impersonate James Dean — and reputedly really piss Big Bob the hell off). We move from the earliest films to the boom period, the “revisionist” works of the 1970s. Representative clips from these justly more famous films illustrate his filmmaking style and subject matter. Altman is a subject of serious fascination in

the Funhouse, so I look forward to studying the various phases that made up his long and intensely fruitful career.

684.) Vintage episode: Every time someone talks about TV being so bold in the 21st century, I think back to the much-maligned (and thoroughly confused) 1970s, and remember when network television actually broke boundaries by throwing previously held notions of taste straight out the window. A good example of this idea was The Dean Martin Show, a variety series that exulted in being slick but haphazard, with the charming presence of Dino carrying the day no matter how dismal the sketch, how weary the song, and how perfunctory the guest-star patter. Dean’s show became outdated by the early ’70s and so the producers hit on the notion of doing TV-friendly “roasts” of celebrities, a la the Friars. The results were pre-packaged hours of insult comedy, that ran the gamut from the totally innocuous (I mean how much can you really insult Jimmy Stewart, anyway?) to the ludicrous (“Man of the Hour” honorees included Evel Knievel, Mr. T, Gabe Kaplan, Ralph Nader, Dan Haggerty, and…George Washington?). Tonight, we’ll take a look back at the Dean Martin roasts, for what is surely the first of several visits into the video archive. The focus, since it’s the most striking element in the shows, is on the insanely racist jokes that were slung at African-American “Men of the Hour,” as well as the standard bits (yes, we’ve got Red Buttons, no, there’ll be no Foster Brooks). We present an overview of the roasts through some of the oldest, saddest, and snottiest, jokes you’ve ever heard. We work our way toward an amazing timepiece, the roast of our favorite all-around entertainer, Sammy Davis Jr., but in the process, you’ll see a number of deceased artistes, who kicked off since we originally shot the host segments, including Frank Gorshin (only present when there’s no Rich Little), Eddie Albert, and roast perennial Nipsey Russell. It was very a different time, and a very, very different form of entertainment – but it’s a hell of a lot more endearing than the present-day procession of stand-ups that makes up the current Comedy Central TV roasts.

685.) This week’s episode is a very retooled vintage show. I reedited the thing, taking out some of my (now very dated) opening comments and put in the remainder of the Peter Sellers segment that is obviously the most dazzlingly strange thing in the show. As always, enjoy and spread the word that classic TV is lurking somewhere on your dial. Happy Holidays to you all! Each Yuletide the tube is filled with reworkings of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. In 1964 a very timely and unusual spin on the tale aired on ABC without commercial interruption as a promotion for the fine work being done by the United Nations (yes, that was when Democrats were in office). The show was called A Carol for Another Christmas, and it was the brainchild of one of TV’s finest writing talents, Rod Serling. The director was Joseph Mankiewicz — coming off his stinging failure with Cleopatra, but still capable of some excellent noir nightmare imagery (perfect for Serling’s often bleak, and mightily depressed, world view). It’s agitprop of a kind, all right, but very entertaining agitprop, and the fact that it features a top-notch cast breathing life into Rod’s often deeply emotional dialogue makes it a lost gem. The Scrooge role is played by Sterling Hayden – with more than a hint of his preceding role as “General Jack D. Ripper” – and the liberal nephew who challenges his beliefs is Ben Gazzara. Hayden’s former real-life role as a friendly HUAC witness always informed his parts as imposing conservative ideologues, and his turn here as “Daniel Grudge” (okay, so Rod’s characters names weren’t so original) is terrific reclamation work for this latter-day liberal. The ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future are all allegorical figures who teach Grudge about the actual horrors of constant global warfare and what my profs used to call “the permanent war economy.” The program’s highlight is the bleak, Twilight Zone-like view of the future which features British actors vigorously breathing life into Serling’s sermons. Robert Shaw plays a truly menacing Ghost who delivers a topical rant about the mid-’60s wave of apathy (the show aired just a few months after the real-life nightmare that was the Kitty Genovese murder). And Peter Sellers came off a two-year stretch that saw him doing some of the best work ever (incl. Strangelove and Shot in the Dark) with an energetic incarnation of the “Great Imperial Me,” an Ayn Rand-style individualist dictator. Serling may not have been a subtle artist, but at his best, he drove home his messages in the most imaginative and entertaining manner possible.

686.) Another super-exclusive for the hardcore film buffs in the viewing

audience: clips from the first two installments of Godard’s Histoire du Cinema. This extremely ambitious and imaginative survey of the (hi)stories of the movies is the work ol’ Uncle Jean concentrated his primary energies on for a whole decade (from ’88 to ’98-as noted by our recent guest, JLG biographer Colin MacCabe), and the result is the ultimate montage of movie images. This ain’t at all like those 30-clips-a-minute Chuck Workman deals you see on the Oscars, though-Godard composed these essays out of photos, overlapping soundtracks, imaginative dissolves and overlays, and his own reflections, complimented by stray voices reading works from classical lit (and we don’t think Workman would ever counterpoint movie stills with masterpieces of art, or segue from Leonard Cohen to opera).

687.) One of the greatest delights of my teenage years as a filmgoer was discovering films that virtually cried out to be reseen; such were the joys of the 1970s work of John Waters, whose brilliantly acidic dialogue was delivered with insane gusto by his “Dreamland” players. I’m proud this week to be speaking to one of the foremost practitioners of his very special brand of sarcasm, the lovely and talented Mink Stole. We spoke to Mink at a recent Chiller Theater convention, and got the lowdown on her seminal work for Waters, from one of the initial super-8 productions to the 16mm cult classics to scene-stealing supporting parts in the more viewer-friendly, bigger-budgeted productions of the post-Divine era. Topics we explore with Ms. Stole include her “exit interview” from the Catholic church (an excuse should never be needed to show the exquisitely blasphemous “rosary job” from Waters’ first perfectly-formed act of provocation, Multiple Maniacs); her special talent for delivering Waters’ most witheringly sarcastic lines of dialogue; and her peculiar sex appeal, which may appear outré to most (including Ms. Stole herself), but was readily apparent to the teenage version of yours truly. Included are my choices for the best bits of her work for Waters (catch the odd glimpse at the camera in the dialogue scene with Divine in Maniacs) and information on her latter-day career as a singer and cameo-role specialist.

688.) A vintage episode this week: The Funhouse celebrates the lives of those who have passed from this mortal coil with deep reverence, but why not salute someone who’s stuck around with us a while? Thus, I return to the topic of the “Dean Martin Roast” to toast the 80th birthday of Jonathan Winters (which occurred November 11th). Before we reach Jon, however, we will once again sample the delights of the roast shows: standups who had solidly defined personas (and could make scripted insults seem fresh), performers playing their best-known TV roles, and icons who just had a little time on their hands. This leads to a full segment from Jonathan, creating as he goes along, saluting Old Blue Eyes as Elwood P. Suggins, bus driver for the Dorsey Orchestra. Unlike most segments on the roasts, Winters’ few appearances weren’t scripted, which is obvious: despite the overplayed laugh track, it’s obvious that Jon got waves of laughter, followed by polite silence, followed by more laughter. He’s the only person besides Don Rickles who truly riffed on the roasts; thus his few appearances were memorable and took away the bad taste left by the ubiquitous Foster Brooks and “Gladys Ormsby.”

689.) We love the high art, we dig the low trash, but what your humble host most enjoys stitching together are musical clips. So this week it’s a vintage-episode pop picnic, centering around three items that have not found their way onto the little silver disc medium everybody’s collecting, for the minute. Our first title is the Beatles doc Let It Be which isn’t the cheeriest Fab Four movie, but has some excellent music, and lively jams on some oldies. Next up is the lengthy and time-capsule-ish documentary Urgh! A Music War (1981), which presents 30 punk and “new wave” acts live in concert; we focus on our faves (X, The Cramps, Devo), the unnaturally young-looking (the Go-Gos) and the underrated (brilliant spoken word artist John Cooper Clarke). Our last segment is a return, after many years, to the world of the Scopitone, the publicity films made for failed film-jukebox experiment of the early ’60s. The films are mostly of French artists (the ones we’re showing at least) doing odd covers of American material or music to which one can twist the night away. Included are Johnny Hallyday, Francoise Hardy, eternal beat chick Juliette Greco, and some babe who does the only solo version of “Twist and Shout” I’ve ever heard. Two personal favorite early ’80s music vids by the Stranglers and Bow-Wow-Wow close out our visual jamboree (I’ve seen ’em a few million times each).

690.) Three items come under scrutiny in the Consumer Guide department this week. The trio have little in common except a relation to the 1960s, and that they all connect to past Funhouse interviews. The first review concerns the new DVD release Dark Shadows Bloopers and Treasures, a compendium of DS-related vid that includes the glorious blooper reel (all flubs appeared on the program), extremely groovy (and yes, sometimes extremely corny) music videos, vintage and post-DS TV commercials, and clips of Jonathan “Barnabas” Frid and cohorts on late ’60s game shows. We make a quantum leap from the classic daytime goth drama to an ongoing mini-retrospective of the work of New Wave icon Jean-Pierre Leaud at the Alliance Francaise, with suitably wondrous sequences from two of the films in the fest. We close with a review of the latest DVD release of D.A. Pennebaker’s milestone Don’t Look Back, with a focus on the newly created Pennebaker docu Dylan ’65 Revisited which, for my money, is a more kinetic and interesting creation than the freshly-scrubbed marathon that is No Direction Home. The Sixties will never die as long as movies and TV clips like these keep surfacing.

691.) I try to be nothing if not thorough on the show, so this week it’s part two of my Deceased Artiste tribute to the inimitable Robert Altman. This time out, three segments present the lesser-seen side of this incredible filmmaker, with a choice selection of clips (only one of which has ever been featured before on the show). The first topic are the “dream films” Altman made in the ’70s, the purest expressions of his sensibility, three films that have nothing whatsoever to do with the large-ensemble pieces for which he was best known. Next I discuss his “theatrical period,” the post-Popeye era in which he created a series of tightly constructed films that did strictly adhere to their scripts and contained the most impressive camerawork outside of European auteurist fare. Last, I counterpoint the only two non-“theatrical” films he made in the 1980s, O.C. & Stiggs and Vincent & Theo. One is a deceptively lackadaisical attack on suburbia and the John Hughes-era teen pic (which Altman detested); the other one of the best portraits of a visual artist in torment. Despite its spinning down into entropy, I highly prize O.C. (although he claimed to hate the script, his attitude melds perfectly with the National Lampoon source material, and what a cast of Funhouse favorites!), and think Vincent proved once and for all — as if proving was needed after the masterful Streamers, Secret Honor, and the other theatrical films — that Altman was not a one-trick pony, and could have, at any point, relocated permanently to Europe and made perfectly brilliant films over there.

692.) Vintage episode: Part one of my lively interview with celebrated French filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier explores his latest film — lacking a U.S. distributor at the moment – Holy Lola, a tale of a French couple looking to adopt in Cambodia. Tavernier is best known for his well-received period pieces (A Sunday in the Country) and his very straightforwardly scripted cross-cultural pieces (Round Midnight), but in recent years he’s made a series of socially conscious pictures that fit into the great “humanist” tradition of French cinema, as well as demonstrate his versatility as a filmmaker. In this initial part of our chat, we tie Lola in to his last two films: Safe Conduct, a personalized chronicle of filmmaking in France during the German occupation that’s half character study/half thriller, and the vastly underrated It All Starts Today, a low-key drama (reminiscent of Loach and Leigh) about a kindergarten teacher in a small French town trying to “make a difference” in the lives of his students (the film, as Tavernier declared in one of the moments I had to exclude from the show, is “not Dead Poet’s Society!”).

693.) As we move closer to another year’s Oscarcast (yawwwwwwwwnnn), it is contingent upon the Funhouse to present tributes to those Deceased Artistes who will be completely forgotten by the Academy or who will be represented by the most obvious, pedestrian film clips. Thus, I have prepared two episodes, themed “high art” and a “low trash,” which present collections of individuals I feel were overlooked when it came time to dishing out the accolades on the obit page. This week’s high-art spree reviews the folks I’ve been covering on the Funhouse blog (http://web.mac.com/mediafunhouse/) but focuses on five gents whose work played in the arthouse. First up, there’s Perry Henzell, director of the film that defined reggae in the 1970s, The Harder They Come. He is followed by another “one-hit wonder” on the U.S. arthouse circuit (who made plenty of films — we’d love to see more), Vilgot Sjoman, master of the I Am Curious duo from the late ’60s. Sjoman’s masterful countryman, cinematographer Sven Nykvist, follows, and then we do a special pair of tributes. The first is to screenwriter Gerard Brach, who wrote some of Roman Polanski’s worst films and a quartet of his finest and, closest to our heart, scripted Marco Ferreri’s immortal Bye Bye Monkey. Last, I salute Jack Palance, not with clips from Shane and (yikes) City Slickers, but with some images I’m fondest of, including his turns in a late-’60s TV horror pic (in which Big Jack played both Henry Jekyll and his monstrous alter-ego), his amazing work for Robert Aldrich, and naturally, his memorable turn as the studio head in Godard’s Contempt.

694.) As the one truly watchable portion of the Oscars, the round-up of the dead folk, approaches, the Funhouse considers it a sacred duty to salute those unsung heroes and heroines who left us in 2006, and would never, ever merit a tribute from the mainstream, multiplex-gratifying film community. This time out, the theme is “low trash,” and the honorees are nearly all female. After a roll-call of the Deceased Artistes who deserve recognition (but I have neither the time nor any entertainingly rare footage), it’s on to a celebration of dames like Audrey Campbell — the actress who played white-slave wrangler “Olga” in a series of ineffably sleazy b&w “roughies” in the ’60s– and the terrific June Ormond, who helped her husband Ron create a series of indisputably deranged Nashville-shot drive-in pics around the same time. We saluted Polanski’s scripter Gerard Brach last week, and it is now time to discuss a polar opposite, the wonderfully imaginative, Judy J. Kushner. Ms. Kushner was Doris Wishman’s niece, and is the one responsible for writing the scripts (such as they are) to Wishman’s most extreme pics, including the otherworldly Double Agent 73. She also wrote the dreamy theme songs to Wishman’s early nudist-camp outings (the sample heard here is warbled by Ralph Sandler of Sandler & Young fame). Providing the perfect counterpoint to last week’s small tribute to the inimitable Sven Nykvist, I salute Gary Graver, who straddled the worlds of art and trash rather miraculously in the 1970s. Graver’s career as a cinematographer encompassed several gigs for Orson Welles (including the last completed masterwork F for Fake) and John Cassavetes, which he alternated with his real bread and butter, shooting the films of Al Adamson and David Friedman. Add to this Graver’s later work as a porn director (directing Traci Lords and lensing such items as The Joy Fuck Club), very many jobs for Fred Olen Ray and his host of pseudonyms, and his work helping Oja Kodar to restore and do road-shows of Welles’ uncompleted works. We close out with a death that shook the Funhouse to its very foundations: the unheralded departure of the “Lady Streetfighter” herself, Renee Harmon. The joys of Ms. Harmon’s deliriously weird work has been sung many times on the Funhouse in the past 13 years (I would love to get her the cult appreciation she deserves), and I couldn’t resist making her the focus of this very reverent salute to folks who diligently worked in what could diplomatically be called the “underbelly” of the film industry.

695.) At the intersection of stand-up comedy, performance art, and sheer insanity exists the professional wrestling phenomenon known as “mic work.” These days it is nearly a lost art — with the exception of the occasional outburst from an old pro like Ric Flair or a modern master of hardcore lunacy like Mick Foley — but in the golden days of the 1960s-80s, giants ruled the arenas, and ranted like nobody’s business on microphones snatched out of announcers’ hands. Such a man was the great Captain Louis Albano, who is our interview subject this week in the Funhouse. The Captain was a man who did it all in the business of what is now called “sports entertainment”: he wrestled, did interviews, participated in stunts, wore eye-offending duds, broke the rules, and managed eighteen tag teams to the championship belt. We conducted our talk with the big man (now a good degree svelter) at the end of a long day at the Chiller Theatre convention, so yours truly was tired, but woken up immediately by the energy of this 73-year-old former “champeen.” (Rarely would I ever leave a moment in which a security guard comes in a room to see when an interview will be finished, but the Captain’s command of the situation deserves an airing.) We discuss his career inside “the squared circle” and his subsequent show biz career, from his 1960s tenure in a mock-Mafia tag team called “The Sicilians” (not appreciated by the boys with the bent noses) to his “breakthrough” feuding with fan and friend Cyndi Lauper to his acting in Brian De Palma’s Wise Guys and the starring role in the extremely ’80s kids’ program The Super Mario Bros. Super Show (no matter how hard I try I am not gonna ever get the closing song, “Do The Mario,” outta my head). It is a testament to the Cap that, although he is prone to tall tales and just a few exaggerations, one of the fully accurate things he mentions is his having raised millions of dollars with Cyndi for victims of multiple sclerosis. They don’t make ’em like Lou anymore, and I was quite pleased to wind him up and let him go….

696.) Vintage episode: We revisit the disturbing, objectionable, but compellingly watchable Goodbye Uncle Tom (1971). We contrast the newly released “director’s cut” of this deranged docu-drama, from the Italian filmmaking duo that gave us Mondo Cane with the English-language version we’ve come to know and wonder at. The film’s oddly graphic depiction of the ways Africans suffered under slavery here in the U.S. is set to the bouncy, irresistible (and woefully out-of-place) melodies of Riz (“More”) Ortolani. The final sequences — in which an early-’70s black radical snaps and kills as many pasty-faced, consumer-society whites as he can get his hands on — aren’t out of place in the longer version of the film, which includes more black militant material… as well as the same unsettling torture scenes and exploitative sexual sequences (the movie was shot in Haiti). The Italian version of the film is a truly radical piece of cinema-that’s just as unpleasant, offensive, and uniquely deranged as the English version. It’s amazing to think that invaluable, U.S.-shot documentary footage snipped from the film (including MLK’s funeral, Dick Gregory running for President, and a Panther meeting) was hiding in the vaults of Signore Jacopetti (the exploitative half of the duo) and Prosperi (the guy who believed — or so he claims — that they were making “documentaries”).

697.) An entire programming day could be comprised out of the many television appearances of the one and only Sammy Davis Jr. We like to do our part every now and again to just dip into the many, many, many kinetic appearances Sam made on TV over a four-decade span. Tonight, I focus on items that have recently shown up on DVD. The first is an outtake from the Bond film Diamonds Are Forever (1971) that found Sammy (nearly) meeting Agent 007 (his old friend Sean Connery). Next we have him being interviewed by ex-Rat Pack troublemaker (and purported procurer) Peter Lawford about James Dean on a late-night ABC special. From Lawford to Griffin, it’s Sam in the midst of a white-hot streak of mid-’60s activity, being interviewed by Merv. And finally, it’s the Candy Man in peak form on two different Playboy series, first as a bespectacled dynamo, singing and dancing up a storm in Hef’s “Penthouse” and then wearing a psychedelic-print shirt but singing Newley and Jolson (with somebody familiar) on a very informal Playboy After Dark (which, they would lead us to believe, wasn’t even rehearsed!).

698.) Few films have made as big an impact on as small a budget as the drive-in landmark Blood Feast (1963). This vintage episode features not one but three short interviews about this insanely silly and supremely entertaining cult classic. First we have a segment of our interview with gore-master Herschell Gordon Lewis; the very articulate Lewis recounts his work on the film, and his even more immaculately campy musical soundtrack. Few sleaze directors could namecheck Berlioz and Stokowski in a few short minutes, but then again, few sleaze directors would’ve rocked their own kettledrums…. We then speak to the mad killer of the piece, the actor who played “crazed Egyptian caterer” Fuad Ramses. Mal Arnold is a very down-to-earth gent who took his very strange role seriously, and is now a cult icon, due to the fact that his “crazy eyes” and prematurely powdered gray hair have shown up on everything from album covers to T-shirts. Lastly, we talk to the heroine of the piece, Playboy Playmate Connie Mason. Like Mr. Arnold, Mason worked with Lewis on two films — she also starred in the gory follow-up, 2000 Maniacs! (1964). She also has the unique distinction of having been a nubile babe who was allowed to live in both of her gore outings (in fact, she never even appears in a scene with the red liquid that doubled for blood). Your obedient servant is not a fan of the gore film genre, but Lewis’s movies are so imaginatively absurd and blissfully threadbare that it’s impossible not to enjoy them (plus, the colors are outta this world).

699.) A face you will recognize, a name you may not, that’s Gerrit Graham, our guest this week in the Funhouse. Part 1 of my interview with this character actor extraordinaire focuses exclusively on his work with Brian De Palma (in his still-exciting “young turk” phase). We start out with a discussion of Gerrit’s improv work at the Second City during the end of the ’60s, which served him well when De Palma’s earliest films called for the cast actors to “vamp” their dialogue based on a few chosen premises. The results can be seen in Greetings (1968), a flashily-edited bit of NYC ’60s brilliance that finds Robert De Niro, Graham, and Jonathan Warden attempting to avoid the draft, find chicks, and expose the Warren Commission all in the space of a few days. The group reconvened in the sequel Hi Mom! (1970), in which Gerrit plays a white radical who takes part in a interactive theater piece called “Be Black, Baby” — an experience that he describes in our interview as being unpredictable, to say the least. We close out part one talking about his memorably over-the-top comic turn as “Beef” in one of our fave Funhouse cult pics, The Phantom of the Paradise (1974), one of the finest comic book/horror/musical/comedies ever made.

700.) To celebrate the very first time that the Funhouse actually airs on the day of Easter, I present with pride some Xtian exploitation. These flicks didn’t play in grindhouses – in fact, some actually ran in church halls – but they are genre-based and some are as downright sleazy as anything that unspooled on the Deuce. After some pleasant words of greeting from yrs truly, we tackle our first auteur of the evening, Donald W. Thompson, who gave America its first series of “Tribulation” movies, back when bestselling hack Tim LaHaye was just a cleric of some kind. Thompson depicted the Rapture in detail in four movies made in Iowa between ’72 and ’83 – except his version owes a lot to Twilight Zone episodes and has the slowest-moving pursuit scenes in the history of cinema. We witness a few key moments from the first two pics in the series, and hear the stirring theme for the Rapture, “I Wish We’d All Been Ready.” Next up we move to the best-ever Christian exploitation filmmaker (I’m willing to step out on the ledge make that proclamation), Ron Ormond. Ormond’s wild career took him from vaudeville to Lash LaRue helmer to maker of classic ’50s (Mesa of Lost Women) and ’60s (The Monster and the Stripper) exploitation, but nothing in his body of work is as mind-bending as his Christian movies. Tonight we feature scenes from the most extreme of all, a Red Scare cautionary tale called If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? (don’t ask). I dare Messrs. Tarantino and Rodriguez to come up with anything as strange and outré as this little number, which shows what life will be like when the Commies take over, replete with countless moments of kids being punished and/or killed. The whole thing is punctuated by inspirational sermons (and laundry lists of things that will hasten the upcoming invasion – he even has a date!) from preacher Estus Pirkle (real name, I swear). Ormond’s films has received attention in fanzines and amongst the diehard fans of trash cinema, but Footmen stands alone as a most extreme “message drama.”

701.) The Consumer Guide department is open for business again, with reviews of four new releases relating to three Funhouse favorites. The first is that consummate master of the cinematic time-slip, Alain Resnais. The DVD release of his most intricate work, Muriel, provides us with a look at the master back when he was at the height of his powers, enthralling and bedeviling arthouse viewers around the world. We then jump from Resnais at his most demanding — and certainly rewarding — to Resnais today, with a review of his latest, incredibly charming study of lonely urbanites, Private Fears in Public Places. The film shows age has indeed mellowed the New Wave master, and he now allows us to thoroughly sympathize and identify with his characters, a sextet of isolated souls hoping to find a connection during a snowy winter in Paris. We then move to another Funhouse hero, Groucho Marx, for a review of the newly released vintage TV disc, Groucho Marx and Redd Foxx, which contains two obscure 1969 stand-up performances by the titular duo (not together). Our last filmic deity is underground legend Kenneth Anger, whose work has finally become available on DVD in gorgeous prints restored by the team at UCLA. There is possibly no finer sensory assault for a late Saturday evening than Anger’s eternally trippy Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, of which we sample a small (but potent) dose.

702.) A recent vintage favorite: One of the leading lights of the new German Cinema and a personal favorite of yours truly, Wim Wenders has been one of European cinema’s most devoted lovers of American culture, and a filmmaker whose work has ranged from modern classics (The American Friend, Wings of Desire) to startlingly intelligent misfires (Until the End of the World) and some of the finest “road movies” ever made (Kings of the Road, Paris Texas). I interviewed Wenders on the occasion of the opening of his latest feature Don’t Come Knocking, scripted by and starring Sam Shepard. We covered a lot of ground, literally jumping decades in the course of our conversation. Topics touched upon include the “homecoming” theme in the Western genre, Wenders’ cinematic view of America, the notion of the “indie” feature, his underrated moviemaking pic The State of Things (featuring a sterling performance by Allen Garfield as a Coppola-like producer), his view of visualizing music on film and, natch, his pride in having collaborated once again with Shepard.

703.) Part two of my interview with character actor extraordinaire Gerrit Graham picks up on our discussion of The Phantom of the Paradise, this time covering the Phan-dom that has been devoted to this terrific 1974 cult movie. We next discuss another rambunctious comedy, Home Movies, an underseen farce about student moviemaking that was probably the last great “unstructured” (and endlessly entertaining) film by Brian De Palma. We leave De Palma behind to talk about cult comedy Used Cars, a pre-gimmick Robert Zemeckis bad-taste comedy that features Gerrit in a showy role as Kurt Russell’s superstitious friend. We lastly touch on the immense amount of TV work he’s done by focusing in on his two appearances on latter day Star Trek series, and his take on the cult-audience phenomenon, for Phantom, Trek, and the very busy Chiller Theatre con he was guesting at.

704.) Vintage episode: The golden age of American International Pictures may be long gone, but the company’s spirit and method (hit on a concept/assign cast/develop ad campaign/write script) does live on in the work done by a few independent video companies cranking out “DVD premiere” features. The bulk of today’s low-budget genre pics are close to unwatchable, but one small studio over in the hinterlands of New Jersey has been producing entertaining and enticing (albeit cable-safe) product for the past few years. Thus this week we present part one of an interview I did with the head of EI Independent studios, Michael Raso. This talk differs from our past discussions with exploitation filmmakers in that Raso is still “in the game” and so offers up-to-date reflections on, essentially, how far a film can go and still qualify for heavy rotation on Cinemax and Showtime. Topics covered include the three no-nos of softcore filmmaking, how the actresses are directed on-set (and how, on certain special occasions, they may perform beyond the call of duty), and the methods of marketing pictures that star cult faves whom the average multiplex moviegoer has never heard of. We focus on EI’s biggest cult heroine, the natural-looking gal-next-door called “Misty Mundae” (currently making films under her real name, Erin Brown), and the way in which she went from being a featured torture victim in no-budget, ultra-violent fetish thrillers to becoming a cult sensation.

705.) “Vintage episode”: Only a select few Deceased Aristes have warranted an entire episode-length tribute on the Funhouse. This week’s subject, Richard Pryor, could fill up several shows, and we still wouldn’t wind up overlapping with the mainstream obits. The show opens with a full-bodied introduction by yours truly, recounting Richard’s high and low points and setting up a mega-montage of clips that come from various sources. We start off with the very “straight” Richard, with scary slicked-back hair, and immediately leap into the best records of Pryor as he appeared in the early ’70s: a raw, honest, confrontational comic who was the only natural successor to Lenny Bruce. I had to skimp on clips from the indispensably strange Dynamite Chicken (which we’ve shown on other occasions) but do highlight Wattstax (directed by the same old white guy who brought you Willy Wonka) and Live and Smokin’. The latter is a 1971 film of Richard performing at the Improv and not getting many laughs from the predominantly white audience. As a result, he riffs off into strange areas – including a bit on his own oral sex habits that is eye-opening to say the least. We also revisit Richard the actor, Richard the vehicle comedian (don’t flinch), and Richard the TV provocateur (with the strangest bit from his short-lived NBC prime-time series). Forget the guy from Superman III and The Toy – this is all about the mustached troublemaker who had a “cool run” and, along with his pal Mudbone, brought new meaning to the N-word, the F-word, and a whole lot of other words.

706.) Returning to our Francophilic fascination, this week we speak to a young actress who has established quite a solid reputation for herself in France in a short period of time, Isild Le Besco. We spoke to Mlle. Le Besco a few weeks back upon the “Rendezvous with French Cinema” premiere of The Untouchable, a film by Benoit Jacquot. Jacquot has cast Le Besco in five of his films to date, and has given her three of her best starring roles: as an innocent encountering the grandmaster of debauchery in Sade; as a young woman on the run with her criminal lover in the brilliant A Tout de Suite; and now, in The Untouchable, as a French woman who discovers her missing father is East Indian. In the interview, I focus on her work with Jacquot, but also discuss her feelings about moving from numerous teenage roles to adult parts (she’s currently 24) and the film she directed about children — thus far unseen in the U.S. — Demi-Tarif. She also offers a reflection on Funhouse favorite Chris Marker, the enigmatic genius filmmaker who was involved with her mother, actress Catherine Belkhodja, who starred in Marker’s Level 5.

707.) The past few films by Guy Maddin have all been considered “events” by his fans, but his latest, Brand Upon the Brain!, truly became an event upon its release: it was shown with live accompaniment by a mini-orchestra, five Foley artists, and a “castrato” singer. The coup de grace was a celebrity narrator (the roster in NYC included poet John Ashbery, Lou Reed, Crispen Glover, Eli Wallach, and Isabella Rossellini), who took a crack at reading the highly melodramatic v.o. that Maddin’s “muse” Louis Negin concocted for the film. In this episode, I speak to Guy about the week-long run of the “live” version of the film, discussing his jittery feelings about the production and his surprise at the different spins his material was given by the celeb narrators. We also talk about the themes that have linked his work thus far, including a wildly Freudian view of the nuclear family, a polymorphous perversity that won’t quit, and humor that ranges from deadpan faux melodrama to raucous Three Stooges-style bonks-in-the-head.

708.) I value the notion of continuity in the Funhouse, and so I’m always glad to be able to continue an ongoing discussion about a filmmaker’s work. We do exactly that this week with Hal Hartley, whom I first interviewed on the program about his film Henry Fool back in 1997; now, ten years later, we discuss the release of his sequel to that film, Fay Grim. We were able to cover a lot of ground with Hal, so much so that our interview will run to two episodes. Here we start out talking about the “day and date” release of Fay, meaning that the film was released to theatres right before — in this case less than a week before — its DVD street date. We then discuss the Hartley features “missing” on DVD (including arguably his finest, Trust) and the way that Fay utilizes one of the finest elements of his work, his quick, deadpan dialogue. We close this installment of the interview with a discussion of the three movies that preceded Fay, which stood the sci-fi/fairy tale/religious allegory genres on their respective heads.

709.) This week it’s part two of my interview with visualist and filmmaker-in-transition Guy Maddin, upon the NYC live-event screenings of his film Brand Upon the Brain! In this section of the interview, we discuss Brand…! at length, starting off with another question about Maddin’s visual style, which is as complex — yet easy to “receive” — as his latter-day, “underground” style of editing. We talk about the Maddin family secrets, which aren’t secrets anymore, but “clues” in the melodramatic storylines that accompany his black-and-white and monochrome fantasies, and also address the presence of a masked, tuxedo and top hat-clad detective in his film, a teen lesbian variant on the glorious “Fantomas” master-thief character, a staple in French literature and cinema that we’ve discussed on the program before. We close out with a discussion of Isabella Rossellini, with whom Guy has now worked three times, and somehow work our way around to mentions of both Mickey Rooney and the revered Dick Shawn, which is always as good place as any to close off an interview with an unique and fascinating filmmaker.

710). We take a break after a solid month of new interview episodes to return once more to the land of the Consumer Guide. This time that land is, once again, located squarely in La Belle France, and four recent DVD releases of French films are the focus. I start out with reviews of two films made by Claude Chabrol and starring Funhouse favorite Isabelle Huppert, the very recent Comedy of Power and the very classic Violette. Huppert has proved to be one of the most daring actresses currently working — taking a risk American lead performers rarely do, namely playing unlikable characters — and the New Waver who’s been branded the “French Hitchcock” (by people who’ve only seen a few of his films) has used her quite well several times, never more so than in the terrific Violette. The next highlighted film is the sensual, strange, and very surreal La Belle Captive, a kinky and imaginative work by novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet that incorporates images by Magritte in a nouveau roman-style plotline that folds in on itself, explains itself, contradicts itself, and is both a daydream and a nightmare. We close out with a review of the Criterion release of Army of Shadows, the Jean-Pierre Melville masterpiece about the French Resistance. Rarely have war heroes seemed less heroic, and more like characters from a rather ambiguous and troubling film noir. Melville remains the most devoted film fan of all film fans, and the noirest, most American Frenchman of them all, and thus we must pay homage every so often to his sacred cinephilic memory.

711.) This week’s show is an unusual timepiece back from the year 1999, when yours truly was just signing off the dreadful service that was WebTV. The one positive aspect that device had was that you could plug it directly into a VCR and “tape” the images, so I couldn’t resist doing a one-off episode on the joys and wonders of the Internet, focusing on various different Funhouse fascinations. The show wound up being tilted towards its final, more outré subject, but that was fine with me. Thus what I intended as a survey of several different kinds of websites instead focuses on one site devoted to one of our key objects of idolatry, Jerry Lewis (see how much he was charging for memorabilia at the turn of the century!) and then a brief look at some cyber-shrines devoted to ladies with very photogenic faces, from silent stars to Drew Barrymore. I then turn to the topic of fetishism on the Net, centering around the twin fixations of the “furry” lifestyle and the adoration of “plushie” animals. At this point, a parade of lovely still-photos of these individuals ensues, supplemented by a reading of a fetish FAQ and one man’s quite singular love of a bunny.

712.) I can scarcely think of anything more to say about this week’s vintage episode from 2000 than what I wrote when it initially aired: “Scenes from the astounding Deafula (1975), the immaculately awful horror feature, made entirely in sign language (with an Ed Wood-like voice track for those hearing viewers). See it–you won’t believe it.” Perhaps I should add that the film’s “mute” character wears what appear to be catfood cans on his hands (see a “mute” character in the world of sign language would be somehow whose hands… oh, forget it!). I will update this only to say that the film has still not received an official release in the U.S. on VHS or DVD since I initially showed it. Some things are just too odd to ever go mainstream….

713.) A vintage episode becomes a “Deceased Artiste” tribute as I re-air my interview with Liz Renay, the stripper/actress/model/unrepentant bad girl. Ms. Renay was one of the most pleasant guests I’ve ever interviewed, and the one who spoke the most about her private life. Thus, we discuss her affairs with Brando and Lancaster, a non-occurrence with Sinatra, and her time in a federal pen for protecting her boyfriend Mickey Cohen. We also talk about her career as an actress in a few of “incredibly strange” cult movies, covering work from Ray Dennis Steckler (she didn’t like it), Renee Harmon (didn’t remember it) to her big-screen comeback as a lethal lady in John Waters’ Desperate Living. Add to that her description of a sexual encounter with Jerry Lewis — without a mention of the carpet sample that figured in the story in her book — and you’ve got one lively conversation in the Funhouse.

714.) I relish the opportunity to mix pop culture and arthouse entertainment, and this week’s Consumer Guide is a classic example of a “leap” that few other shows would even contemplate. We start out with reviews of two “nostalgia”-oriented DVD releases — one about stand-up comics on The Tonight Show and another on lounge veteran Buddy Greco – and then move straight into the avant-garde. The Kino box set of Experimental Cinema includes hours of rare avant-garde films, including the first works of many notable filmmakers from the American and European “underground.” I concentrate on the work of Stan Brakhage, who is represented here by four of his first five short films, which include things one never associates with Brakhage’s later classic avant-garde milestones, including a make-out scene, a fight, a character’s fatal fall, and (gasp) some slapstick! I also discuss the set’s centerpiece, an amazingly potent act of provocation called Venom and Eternity (1951) by Isidore Isou that attempts to rile up viewers by lecturing them on art and cinema, starting up a narrative and then stopping it suddenly, presenting bizarre “noise poems,” and showing footage that has been drawn on and otherwise disfigured! We close out with a review of the new Criterion Collection release of La Jetee and Sans Soleil, two films by the sublime cinematic essayist Chris Marker; as usual, we focus more on Criterion’s rare extras than the films themselves (which I’ve featured before on the program).

715.) Vintage episode: Israeli director Amos Gitai is a fascinating filmmaker whose work contains distinct elements of both Middle Eastern and European cinema. We spoke to him on the occasion of the NYC premiere of his new film Free Zone (starring Natalie Portman) about the themes in his work, his unique visual style, and the ways in which he has tackled Jewish issues on film in an engaging, somewhat allegorical fashion. Most important of all to Gitai’s style is his use of long takes, established in his early documentary work for Israeli television. Gitai’s long takes establish his characters and their surroundings in a concrete, no-nonsense fashion, but they also have a hypnotic, dreamlike quality that makes his films thoroughly unique and removes them entirely from the literary and music-video models that predominate in mainstream filmmaking. Part one of our chat concentrates on his Israeli fiction films, with the focus on the orthodox Jewish drama Kadosh, his personal war chronicle Kippur, the vibrant (and very dreamlike) slice of Israeli history Kedma, and his recent ensemble comedy set in an apartment complex, Alila. For a man who values “ambiguities” above all, Gitai is also a plain speaker and a very unique artist whose attitude towards the movies we very much enjoy – better to “digest” a picture than be forcefed a bunch of ideas and situations.

716.) Part two of my vintage interview with Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai features his further reflections on the relationship between filmmakers and their audience, as well as a discussion of his boldly imaginative Golem trilogy, made in Paris when he was an “exile” from his home country. Lastly, we discuss his working relationship with the legendary Sam Fuller, and his admiration for one of our Funhouse icons, Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Of special interest is an account of a large-scale theater production Mr. Gitai staged in Italy that starred Fuller and Hanna Schygulla among many others. Included in the show are clips from his controversial 1982 documentary Field Diary (the film that cemented his “exile” status for a time), his Golem pictures, and a particularly amusing bit where Hanna and Sam discuss a mutual acquaintance who works as a phone-sex operator.

717.) Since the rerun networks (oh, excuse me, “classic TV”) show absolutely nothing in the way of variety shows — and very little in the way of anything pre 1980 — I feel it contingent upon the Funhouse to move back to the heyday of the format, the 1960s, when “old” met “new” and the guest-star rosters were just mind-blistering. This week’s episode salutes two very different sex symbols. The first is the very unlikely debauched genius Serge Gainsbourg, and the second is the Welsh wonderboy Tom “It’s Not Unusual” Jones. We have two featured segments, the first being scenes from an extremely rare 1966 French Jones special that happened to feature Serge as one of the musical guests. Tom spoke no French and communicates with only one guest (in English), but the guest-star roster of this music-only special is truly splendiferous: Serge, Francoise Hardy, an insanely gorgeous and melodically sound Marianne Faithfull, and two acts that once seen will not be easily forgotten (Eric Charden and ye-ye gal “Pussy Cat”). We move from TJ in the City of Lights to TJ in the UK, as I present of a review of, and a round-up of clips from, the new This is Tom Jones box set. The theme of the box is (taking a leaf from earlier Sullivan and Cavett collections) “Rock ’n’ Roll Legends,” but the truly important thing about the box is the way that it mingles some dated and not-so-dated comedy (Pat Paulsen, the Committee, the Ace Trucking Company, Richard Pryor) with a simply terrific assortment of musical guests (spotlighting Tom’s duets with Aretha, Joe Cocker, and Janis).

718.) On this week’s vintage episode we return to my interview with the late Brion James, character actor extraordinaire. Conducted back in 1999 at the Chiller Theatre convention in New Jersey, my talk with James was one of the most free-wheeling in Funhouse history, with our guest keeping the conversation moving with some truly candid anecdotes about his career as a Hollywood journeyman — interspersed with some wild facial antics and wiseacre remarks to yrs truly. In this part of the interview, we talk about his background as a stand-up comic with fellow character actor emeritus Tim Thomerson, and his early days sponging off acting-teacher legend Stella Adler. We work our way up to his standout part in the cult classic Blade Runner (1982), and wind up with his assessment of his many villainous redneck and neo-Nazi roles in some notable major studio pics and more than a few straight-to-video outings.

719.) Certain American filmmakers are better known in Europe than they are here in the States, and one of them is Jerry Schatzberg, who made a trio of utterly superb movies during the heyday of the “maverick” movement in Hollywood and has continued to work as both a successful photographer and filmmaker in the decades since. Some of his still images are iconic portraits of the Sixties (check them out at his website, www.jerryschatzberg.com), but my interview with the gentleman focuses primarily on his filmmaking. The first part of our talk spotlights his first two features, Puzzle of a Downfall Child, a study of a “past her prime” fashion model reflecting on her past (played to perfection by a young Faye Dunaway) and the seminal New York picture The Panic in Needle Park (1971), which gave Al Pacino his first starring movie role. Mr. Schatzberg offers an insight into what it was like making stark, uncompromising dramas during that seminal time in American film, and supplies background information on both movies, with reflections on Anne Saint Marie (the real-life inspiration for Puzzle), Dunaway, Pacino, Panic costar Kitty Winn (who won the Best Actress at Cannes that year), and his screenwriters, Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, and the “maverick” scripter Carol Eastman (who wrote Five Easy Pieces right after Puzzle).

720.) As Labor Day approaches, it’s time again once more for the annual Funhouse tribute to Jerry Lewis. Since I’ve explored his work for so many years on the program, this time I’ve decided to “dig deep” (as Jer encourages us to do every year on the telethon), and have come up with two of the more, let us say “demanding” projects Jerry was involved with. The first is the insanely awful movie that went to straight-to-video and remains the worst-ever adaptation of the wonderful work of Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Slapstick of Another Kind (different clips from the ones on the old Funhouse blog and YouTube). Each decade has its own brand of overwhelmingly misguided movie projects, and Slapstick truly belongs to the Reagan era. The cast is sublime (Jerry, Madeline Kahn, Marty Feldman, Jim Backus, Sam Fuller, Pat Morita) but the source material is uncertain and the approach is simply, well… you’ll see. We then provide viewers with a respite while some interesting footage of Jerry as testimonial speaker is shown, and then we move on to the feature of the evening, scenes from the landmark Jerry Lewis Show from 1963, the live primetime Saturday night project that still can stun 44 years down the line. It’s a variety show with few guests, and Jer is the center attraction — little more needs to be said.

721.) In our vintage episode department this week, we have the second and final part of my very friendly and sometimes strange chat with the late character actor Brion James. I spoke to Mr. James just a few months before his very premature death, and got him to talk at length about his rich and varied career in both classic mainstream action pics and the sleaziest straight-to-video titles. Few performers could switch from talking about acting opposite Wings Hauser and G. Gordon Liddy in a purebred schlocker one minute, and then recount his experiences improvising with the elite in Robert Altman’s mainstream comeback picture The Player the next, but James did just that. He also recounts his experiences with directors he liked a lot (Sam Raimi and Walter Hill, for whom he worked five times) and ones he hated (Paul Verhoeven, who put he and his castmates through hell on the plague picture Flesh + Blood). We end on a wistful note (wistful in retrospect) as Mr. James talked about his future plans as a producer-actor, plans he unfortunately couldn’t act upon (he did appear in one more film, the desert-bound Dogma feature The King is Alive).

722.) The death of one of the cinema’s great innovators deserved something a little different on the program, and so instead of launching into a biographical, chronological tribute to the late, great Ingmar Bergman in my first tribute episode, I decided to focus on the period of his work that has fascinated me the most, the 1960s. (The equally brilliant work from the breakthrough ’50s and the tortured-relationship ’70s will show up in the second episode.) This gave me the task of reliving this amazing group of “pictures” (Bergman’s own preferred English noun), and trying to put in perspective how this great artist responded to the social and cultural “rupture” that the Sixties represented. I start out with a discussion of the two trends in Bergman obituaries (wistful and downright wrong), and then head into the six-pack of films that remain as mind-warping today as when they first came out, starting with the 1963 fever dream The Silence and ending with the direct-address, things-fall-apart scenario The Passion of Anna (1969). Those who think of Bergman as a dryly literary or overly theatrical filmmaker might be thrown off, and hopefully mindfucked, by the bold modernity (and just plain strangeness) of these films. Included among them is the classic Persona, the blissfully out-there Hour of the Wolf (the single greatest statement on insomnia ever), and The Passion of Anna, spotlighted here by a Liv Ullmann monologue which Bergman cited in an interview as one of his favorite pieces of acting (for her part, Ullmann reveals on the DVD that a strategic edit he made in the film to another monologue bothers her to this day). Perhaps the oddest title is The Ritual (1969), a wonderfully warped TV film by Bergman about three performers under investigation by a judge/censor, who then voluntarily takes part in their bizarre stage ritual. God (or nothing), how I love this stuff.

723) Vintage ep: My first impulse upon being the recipient of rare films is to share them with the Funhouse audience, and so it is Consumer Guide time once again, this episode focusing on items that are available through a mail-order service, www.mondovideobasement.com , run by the oft-mentioned-on-the-Funhouse M. Faust of Buffaloland. The first offering is something that, while not in the category of Bye Bye Monkey, is still a whizbang of a romance, Max, Mon Amour, the story of a staid Englishwoman (Charlotte Rampling) who falls in love with a chimp. The film is intended as a social satire, but it initially succeeds because it is just so matter-of-fact about the woman-monkey coupling (which we never see, by the way). Its pedigree is very fine: it was directed by Nagisa Oshima (In the Realm of the Senses), written by Jean-Claude Carrière (who scripted films for Buñuel and Polanski, and also wrote the screenplay for The Tin Drum) and costars Anthony Higgins and former Almódovar favorite Victoria Abril. After that, we leave the monkeys behind (for a few minutes) to present a wildly imaginative crime thriller from France that was never distributed in the U.S., Vidocq. Centering around a real-life figure who started as a criminal, founded the modern French police force, and then wound up a private investigator, the film uses CGI for the right reason: to create atmosphere, rev up the visuals, and evoke a different period in a quite unique way. Vidocq (2001) might seem derivative these days, but that’s only because the innovations favored by its director, a guy who likes to be called “Pitof,” have been used so often since this feature appeared in France, and one of Pitof’s former bosses, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, used CGI in similar ways in his recent films. Whatever the case, Depardieu is Vidocq, Vidocq is dead, and he died battling a supervillain named “The Alchemist” who wears a mirror for a mask — a pretty solid premise for a comic book adventure. Last up is the piece de resistance (you may wanna resist it, but I ain’t lettin’ ya), Thundercrack! A cult movie extraordinaire, this 1975 b&w epic is a “old dark house” comedy of the strangest sort, a camp vision created by director Curt McDowell and a Funhouse favorite, scripter-star George Kuchar. A group of people all wind up at the house of a cracked Southern belle one rainy evening; the group proceeds to engage in various couplings, until George comes along, with his love of a female gorilla…. The film is something I’ve wanted to get a good copy of for years to show on the program, but I still couldn’t air at least three of the film’s funnier sequences because they all involve naked folks having sex (or just people in the act of touching ’emselves down below), something that still is a no-go on American TV because, well, you know … kids could be watching or something (or adults with brains the size of figs). The Funhouse is fearless, but American TV — and America in general — ain’t gonna grow up anytime soon, so we’ll still have to trim the original, the courageously awful, and the truly deranged items, like Thundercrack!

724) In thinking over the filmmakers whose virtues I extolled in the first years of the Funhouse, I realize that some of the newer names (from that time) have become arthouse staples (Von Trier), gotten erratic distribution but still receive U.S. plays (Kaurismaki), or have kept up a modest but steady pace and revisited us in the Funhouse (recent return guests Maddin and Hartley). The one who seems to have left the radar entirely is Leos Carax, the young French filmmaker who acquired a small but devoted cult outside France, but was generally rejected by French critics and audiences alike. Maker of only four films to date, he crafted one of the most romantic movies of the latter part of the 20th century (Les Amants du Pont-Neuf, aka, crappy U.S. title, Lovers on the Bridge) and showed a New Wave-like enthusiastic, cinephilic style in his first two films (Boy Meets Girl and Bad Blood) while introducing audiences to Juliette Binoche and Julie Delpy. This week we revisit my 2000 interview with Carax, when he was here in New York promoting his fourth feature, the very challenging and intentionally discordant Pola X. As we had discussed Pola already in the first part of the interview, on this program we talked about the negative reception that Carax’s earlier films had received in France, and the great acclaim he received in other countries, as well as his work as a film critic (for the esteemed Cahiers du Cinema, home of young aspiring filmmakers for quite a while), and touched upon my favorite aspect of his work, his superb use of popular music, particularly the songs of David Bowie.

725) Part two of my interview with filmmaker Jerry Schatzberg picks up right where we left off: in the fascinating “maverick” period of early ’70s cinema, when the major studios were funding personal, adult movies that withstand repeating viewings and definitely qualify as the best American cinema has to offer. Such is the case with Scarecrow (1973), Mr. Schatzberg’s road movie with Gene Hackman and Al Pacino that has garnered a strong cult among filmmakers (most of them French) and novelists (one or two American). He offers reflections on the picture, discussing the acting methods of its star duo and the relative ease with which it was made, despite its being shot on location across the U.S. We move on to talk about a few of Mr. Schatzberg’s later films (he has worked frequently with stars on the rise, like Morgan Freeman in Street Smart, 1987), what Harold Pinter is like when he’s drunk, and Schatzberg’s preference for “downer” scenarios. We finish off by touching on his iconic ’60s photographs, from studies of Bob Dylan (including the Blonde on Blonde cover) to the Mothers and the Stones, and many of the ’60s most beautiful actresses.

726.) This week’s vintage episode: This time out we present clips from newly rediscovered atrocities from the 1970s, the decade that never ceases to yield bizarre culture-clash material. The topic is a certain Linda Lovelace, who received only a cursory Deceased Artiste tribute in the Funhouse some time back, but now is the subject of a DVD release that contains two of her three feature films – and, yes, these are the two that nobody’s heard of. The first is the recently exhumed Deep Throat 2, thought to be lost to the ages, but which is now available for our wincing, moaning (no, not that kind) pleasure. The movie was written and directed by Funhouse fave Joe Sarno, but it is unlike any of his other work, and is quite unlike its predecessor, in that it’s a sex farce without any sex. The cast may include the very nice but thespically-challenged Linda, Harry Reems, Jamie Gillis, and other recognizable hardcore figures, but there is only a modicum of nudity, and the lame spy plot leads to the slowest-paced chase and pie fight in history. This highly misleading head-scratcher is handily topped by Ms. Lovelace’s first and only “legit” movie, Linda Lovelace for President, a miraculously bad item that finds an outsized cast of familiar faces moving through a would-be Mad-mag spoof of politics and the “social scene” in the most liberated decade any of us have ever seen. The cast includes a host of our favorite character people, including Art Metrano, the Monkees’ Micky Dolenz, one-time Kennedy impersonator Vaughn Meader, and Chuck McCann (using the screen names “Fetuchine Alfredo” and “Alfredo Fetuchine” for his dual role; no reason to screw up the kiddie-show career with something like this on his list of credits). The picture has to be seen to be believed – suffice it to say that Ms. Lovelace’s “talent” is mentioned several times (but not shown), and her nominating committee includes an Arab sheik, a black militant, a limp-wristed gay, a butch lesbian, a Chinese communist, and (natch) a Nazi. They just don’t make ’em like this anymore…..

727.) The Funhouse covers a broad range of material, but it seems like the only times I can weave different passions of mine into a single episode are when I do Deceased Artiste tributes or when we enter the Consumer Guide department. This week we adjourn once again into the latter arena, and so I proudly present reviews of three completely unrelated items that happen to completely relate to what I’ve been doing on the show for the past 14 years. The first item up for review is the new collection of Robert Klein’s HBO specials. I’ve been a fan of Klein’s since the early ’70s, when I committed his first two LPs to memory, and so I was quite glad to get lost in three decades of his wry observations about pop culture, memories of the ’50s, and scary mouth-theremin sounds. Next up is a restoration of the 1935 adventure classic She which has been colorized, but this time it’s with a difference — golden fanboy Ray Harryhausen supervised the colorization process. The film’s dialogue may be corny but its imagery is unforgettable, and it’s got to be the only classically styled soldier-of-fortune adventure epic to have Busby Berkeley-style tribal musical numbers. I close out with a review of the new DVD collection of Francois Ozon’s short films. We’ve been lucky enough to be able to follow Ozon’s career since his first features appeared on U.S. screens, and his short films are perfect examples of his characteristic mixture of dark, mocking humor and kinkiness.

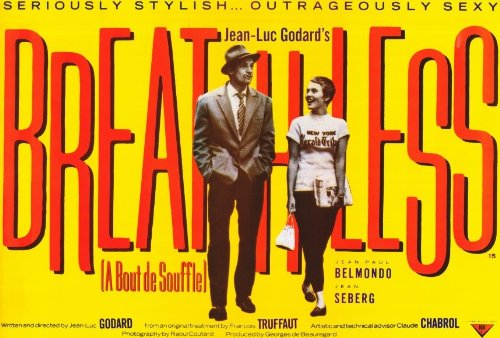

728.) The Consumer Guide department this week is all masterpieces, all the time. The three items under review are not just my idea of perfection, they are films that actually changed the way films are made. First up is Battleship Potemkin. Eisenstein’s classic has been analyzed, dissected, examined, and otherwise studied over the past 82 years — but were we actually seeing what he had really shot and edited? A new release from Kino says actually, no, as we finally see the missing shots from the Odessa Steps sequences and witness the way images were re-ordered and, in fact, re-edited by German censors (who, in a rare bit of intra-war pacifism, trimmed what they felt were excessively violent shots out of the film). Since the German cut of the film is what we have been watching all these years, the Kino release presents the first look at Eisenstein’s original edit of the most studied sequence of shots in film history. I next turn to the Criterion release of Godard’s Breathless, which contains countless nifty supplements that chart the making of the film in fascinating detail, and offer new and vintage clips that feature the reflections of everyone who participated, including our hero Uncle Jean (seen only in the vintage ones, of course). I close out with a review of The Films of Kenneth Anger Volume 2, which includes the most influential and kinetic American underground film of all time, Scorpio Rising, plus Anger’s Satanic pics and his comments on the films (which don’t include personal revelations of any kind, but does have worrywart Ken warning Marianne Faithfull in the present tense that, if she doesn’t stop smoking soon, she’ll die of it!).