1249.) Vintage: To honor the memory of the recently departed Shelley Berman, I re-air (in its new, spiffy, digitized form) my interview with Mr. Berman from 2002. The first of two episodes finds Shelley talking about his early experiences on stage as an actor and sketch comedian, in particular his work with The Compass (the Chicago group that also included Nichols and May and Barbara Harris). We discuss his standup comedy (which made him a strong precursor to every neurotic comic out there), and some of his acting work, in particular his starring role on a memorable Twilight Zone and his appearance as a peeved dentist on The Mary Tyler Moore Show. In the process he shares his opinions on voicemail (anti) and the work of Kafka (pro).

1250.) Vintage: Our guest gets cranky and very funny in the now-digitized, second (and last) part of my interview with the late Shelley Berman from 2002. We start out talking about him being bothered by other drivers and then segue into a discussion of his great (and very touching) “father and son” routine. Mr. Berman then takes some very funny swipes at public access and we end up discussing the merits and non-merits of NYC. All in all, it was a lovely talk with a lovely gentleman who just pretended to be a cranky old man – well, some of that was true, but like the gent whose father he played in his last terrific role, Larry David, he got out all his crankiness in his comedy. One of the nicest interviews I’ve done.

1251.) Movies “disappear” for different reasons. In the case of the movie I’m discussing and showing excerpts from this week it is most likely because the film’s true “auteur” was not pleased with the result. Well, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., might’ve disliked Happy Birthday, Wanda June (1971), but I love some aspects of it and the rest is perfectly in tune with our perennial discussion in the Funhouse about the Sixties being “the gift that keeps on giving and giving and giving….” It’s essentially a filmed play, with a very simple set-up: a previously missing Great White Hunter type (Rod Steiger) returns to his Manhattan family apartment and finds that his wife has moved on from him, as she’s dating not one but two “weak sister” characters. His son (Steven Paul, who later made the *stunningly bad* Vonnegut adaptation Slapstick of Another Kind) is curious about his dad’s adventures but doesn’t seem to cotton to his dog-eat-dog (or, more appropriately, hunter-shoots-prey) philosophy of life. Besides the joy of seeing Steiger thoroughly devour his role, two things distinguish the film: a number of fantasy sequences, in which we see what people do for fun in Heaven (clue: it’s a cruise-ship specialty), and a scene-stealing performance by William Hickey as Steiger’s thin, confused sidekick (who actually conveys the film’s message about American violence in one stirring, unexpected dialogue exchange).

1252.) Following the trail of my favorite filmmakers takes us down some interesting alleys on the show. This week I review and show excerpts from a comedy by Takeshi Kitano (aka Beat Takeshi) that hasn’t been shown in America at all, Ryuzo and His Seven Henchmen (2015). The film is a yakuza farce about old gangsters who are bored with being treated “old farts” (the single most-used phrase in the movie), so they band together as a new criminal gang. The situation is somewhat familiar to American viewers, but Kitano’s take on the scenario is that the old-fart yakuzas face off with the new criminal generation: crooks in suits who do their thieving and conniving in corporate boardrooms. Beat has played a yakuza numerous times over the past few years, so here he cast himself in a supporting role as a cop who has a soft spot for the old gangsters (as one suspects the real Kitano does). I’m happy to share scenes from this film, which has never been seen on these shores.

1253.) Part one of my interview with cinematographer Caroline Champetier, who has done brilliant work with a host of the greatest filmmakers working in France over the past 35 years. This part of our chat begins with her discussing the somewhat recent films she was doing Q&As for at the Alliance Francaise. The first is Anne Fontaine’s fact-based WWII drama Les Innocentes (2016) and the second is Leos Carax’s triumphantly imaginative and strange Holy Motors (2012). We talk about one of the most flawlessly shot scenes in the latter and she discusses her high-def camera of choice. From there we move backward to the beginning of her career, when she was an assistant to the great d.p. William Lubtchansky (a great collaborator of Rivette). We talk about her work on Chantal Akerman’s 1982 film Toute Une Nuit (like Holy Motors, it’s a journey through one evening; although in this case it’s taken by many different characters) and Daniele Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s ultra-deadpan adaptation of Kafka, Class Relations (1984).

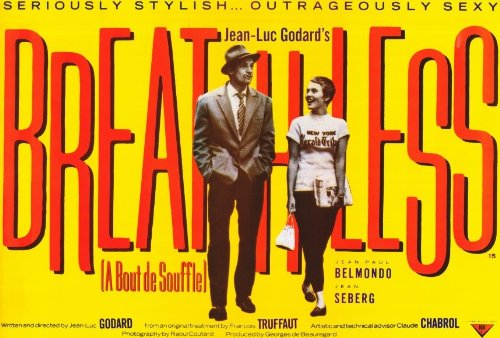

1254.) Part two of my interview with the great French cinematographer Caroline Champetier. In this section of our talk, I asked her about two of my all-time Funhouse favorites. First up is a discussion of her work on films and videos with the inimitable Uncle Jean (aka Jean-Luc Godard). I asked her to talk about the comedic “Uncle Jean” character he has played in several films (including two that she shot). She also addressed his reputation as “a master of lighting” (she had a very interesting answer to that). We talk about his indoor and outdoor shoots, as well as the time that she was utilized as an (unbilled) actresss in one of his fiction films. From there we move on to her work with Godard’s “new wave” comrade, Jacques Rivette; Champetier was one of the two cinematographers on Rivette’s great “comeback” film Le Pont du Nord (1980). She talks about that shoot, which was a truly minimalist, extremely “new wave” affair. We close out on a discussion of her work shooting Rivette’s The Gang of Four (1989) on her own – the film is a combination of genres (character study, thriller, political drama), in the classic Rivette fashion.

1255.) Vintage: Back in the British comedy department, I have an update on the career of that most deadpan and sarcastic of comics, Mr. Stewart Lee. This week’s episode includes commentary on, and clips from, the very recently aired second season of his “Stewart Lee’s Comedy Vehicle.” This year the show had less of a budget (thus, only one short sketch per show, at the close) but contained a “devil’s advocate” in the form of producer Armando Iannucci (“I’m Alan Partridge,” “The Thick of It”). Iannucci persecutes Lee in every episode (“will there be any jokes this week, Stew?”), and the show is all the better for it. I am happy to put the spotlight on one of the more bizarre episodes, in which Stew renders onto us a Tristram Shandy-like discussion of charity that winds up being about crisps, his grandfather’s racism, and the King of Monsters.

1256.) The first of three episodes devoted to the great work of the brilliantly subversive filmmaker Robert Aldrich. These shows came out of watching (and being annoyed by) the overwrought miniseries “Feud,” which dragged Aldrich’s reputation through the mud and ignored his many accomplishments making independent films with and without studio backing. In this episode I focus entirely on the Fifties and the string of genre pictures he made that overturn the genres in question. The films included in the show range from his first adventure/noir film World for Ransom to his mid-Fifties slew of splendid genre movies, including two great Westerns (both with Burt Lancaster), a “woman’s picture” (with Joan Crawford), a why-Hollywood-is-evil melodrama, and two of the greatest subversive films ever, his anti-war war movie Attack! (1956) and one of the best (and arguably the “last”) noirs ever, Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

1257.) Part two of my ongoing tribute to Robert Aldrich moves into the 1960s, the decade that saw his two biggest box office hits. I start out with a discussion of the joys and motifs of his work and with one leftover from the Fifties, the vastly underrated Ten Seconds to Hell (1959) with Jack Palance and Jeff Chandler as demolition experts who make a very grim wager. From that point on it’s all Sixties (“the gift that keeps on giving and giving and…”) with Aldrich’s extremely popular (and truly iconic) horror thriller/show-biz deconstruction What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and its better-than-you-think follow-up Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964). From that one-two punch of old haunted ladies I move on to his other giant hit, The Dirty Dozen (1967), a seminal “guy movie” as well as an anarchic action pic that paved the way for The Wild Bunch and M*A*S*H. And, because Aldrich was indeed a trailblazing independent filmmaker, I close out with the two films in which he invested his “Dirty” money. Both are about actresses ground down and destroyed by show-biz – the first is the truly dark and arch The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968) and the second is the groundbreaking lesbian drama The Killing of Sister George (also ’68), which was given an “X” rating when it came out. George is indeed dated but is still another fascinating Aldrich portrait of a character whose life is out of her control.

1258.) Vintage: Roy Andersson is an enigma: a Swedish filmmaker who crafts brilliant deadpan comedies out of a series of sequences (each one of which is a single, often dazzling, long shot); an artist who reinvented himself, coming up with a new style nearly 25 years after his start in the business (and then making only three subsequent features in the next 20 years); and an admitted fan of certain filmmakers (Bunuel in particular – and Laurel and Hardy!) who credits certain painters as being the biggest influences on his filmmaking. I was very proud to interview Mr. Andersson on the NYC debut of his new film A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence. In the first part of the interview we discuss how Pigeon differs from the preceding films, his fine-art obsessions (as well as the comics he read as a kid), plus his favorite movie comedians. Also: a discussion of his storyboarding process and his opinions on religious superstition.

1259.) No show aired, thanks to fuck-up at Access HQ.

1260.) Vintage: Part two of my interview with the brilliant Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson delves deeper into his career and his superbly stylized visuals. In this segment of our chat we talk about the introduction of scenes set in other eras in his new film A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, as well as his use of dream scenarios in his episodic features. We discuss his first film, A Swedish Love Story (1970), and how it winds up veering away from its central characters (a pair of lovestruck teens, played by actual teenage performers). He also talks about the ways in which his direction of literally hundreds of wonderfully deadpan TV commercials helped him forge his trademark visual style. We finish off this portion of the interview with a discussion of his transitional short “World of Glory” (1990), which presented the “new” Andersson style to moviegoers.

1261.) I return to the Consumer Guide department this week with reviews of three UK performance videos from the Welsh DVD company Go Faster Stripe (which now, like everyone, offers their wares as all-region downloads). The first is a round-up of comedy videos and sketches by radio DJ Adam Buxton, including a wonderful guide to bald American celebrities. Next up is Richard Herring, whose show Happy Now? is about the concept of happiness – what leads to it, how can we reach that state, and the most significant question, can we keep it? In the process of pondering this existential quandary, Rich also touches on deranged nursery rhymes, obscene t-shirts, and how he could possibly, accidentally kill his baby (no sappy family fare here). I close out with a review of Mark Thomas’ The Red Shed, a lively monologue about the importance of a small socialist club to the small town of Wakefield and, more importantly, how some of our fondest memories might just be delusions that sound better the more we tell them to others.

1262.) The third and final part of my interview with the great French cinematographer Caroline Champetier covers a lot of ground and still doesn’t put a dent in her amazing filmography. First off we talk about her frequent work with a performer, namely the legendary Jeanne Moreau. From that we move to one of the directors she’s worked with numerous times, Benoit Jacquot, and the film of his that is her favorite, A Single Girl (an experiment in telling a story in “real time”). From that we move on to her work with filmmakers Jacques Doillon and Margarethe von Trotta. The last filmmaker we discuss is Champetier herself, who has directed and shot a handful of features, including a telefilm biopic about the Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot. I’m glad to have discussed a broad range of Champetier’s work with her – she’s done cinematography for some of the greatest films of the last few decades.

1263.) Vintage [digitized and updated with titles]: A bit of a different Funhouse episode this week, as movies, classic TV, and indelible pop music aren’t even mentioned (gasp), but I am happy to be interviewing a comedian’s comedian, a stand-up who has been toiling at his trade for over 35 years now and is currently developing a one-man show that weaves together all the threads of his work to date, from obsessive television-viewing to quantum physics. My guest is Chris Rush, whose name may not be a household word, but who was hailed as a uniquely funny individual by George Carlin and Jay Leno, and has kept at it since the Nixon era, honing his comic radar and perfecting his wonderfully fast, absurdist, and very, very New York view of the universe. The topics I cover with Chris range indeed from the primacy of laughter, the National Lampoon, Lenny Bruce, and the history of the dreaded Catholic Church, to what he calls quantum “oh wow” physics and how reality is really, really non-local.

1264.) Two British political comedians are the focus of this Consumer Guide episode centered around the output of the Welsh DVD company (which now does region-free downloads) Go Faster Stripe. First up is Andy Zaltzman, a “Satirist for hire” (his DVD title) who offers amusing insights into international economics, his own lapsed Judaism, and the colonial urge of the Brits. (In the DVD he offers some snappy remarks about his ex-comedy partner, some guy named John Oliver.) Up next is the work of Mark Thomas, a comedian whose shows are beautifully refined one-man performance pieces. The first one I’m reviewing is “Bravo Figaro,” about his working class carpenter father’s love of opera. The second is the beautiful character study “Cuckooed,” which tells the story of Thomas’s friendship with another political activist that ended when Thomas’s friend was revealed to be a corporate spy who had infiltrated the anti-arms movement in the UK. The show is both funny and insightful, but also offers a bracing portrait of the way that corporations infiltrate leftist movements and a sad reflection on how money can ultimately change (and end) a friendship.

1265.) A wonderfully bizarro film like no other, Themroc is a study in personal revolution. The adventuresome Michel Piccoli plays the lead character, a grunting, yelling worker (the whole film is in a made-up language that has a little – but not much – to do with French) who goes mad one day. He is fired from his job, so he goes home, sleeps with his sister, bricks up the door to his room, bashes a hole in the wall leading out to a courtyard, tosses furniture out the newfound hole, repels the cops (even roasting and eating one), and then has a mindblowing orgy (including the great Patrick Dewaere in one of his first “adult” roles), because, you know, that’s what you do. A product of the Sixties (although made in ’73, which is still the Sixties), Themroc is an amazingly brazen act of provocation that defies laws of logic, language, and linearity. It’s nuts and proud to be so.

1266.) A Deceased Artiste tribute to Joseph Bologna, a great comic actor whose comedy-writing partnership with his wife, writer-actress Renee Taylor, was the most unique aspect of his career. This week I discuss their partnership and show clips from three films they wrote. The first, Lovers and Other Strangers (1970), is a perfect little portrait of different couples attending a wedding – one couple discovering each other, one wanting a divorce, one that stays together but never stops arguing, another where the husband repeatedly cheats, and one where the couple simply tolerate each other (the last two are, naturally enough, the parents). The second film, Made for Each Other (1971), was written by and stars Taylor and Bologna as an utterly neurotic couple who both act out their emotions in public (a lot). The final film is Love Is All There Is (1996), a film written, directed by, and starring Taylor and Bologna that offers a modern farcical update on “Romeo and Juliet” with a cast of familiar faces (and the young “Juliet” character happened to be played by a very young Angelina Jolie).

1267.) Returning to a Funhouse favorite, this week I begin a small group of episodes devoted to the work of tele-playwright extraordinaire Dennis Potter. In this episode, I show scenes from two of his earlier works, starting with the 1968 play “A Beast With Two Backs.” Set in the 19th century in Potter’s home town of the Forest of Dean, it’s a grim and disturbing tale about a murder and the narrow-mindedness of small-town Christians. I then move back to one of Potter’s earliest surviving plays, “Where the Buffalo Roam” (1966). The show is a rough draft for the many stories of dreamers influenced by pop culture that Potter wrote in later years. In this instance, an illiterate young Welsh man loves Westerns so much he believes he lives in one. This upsets his teachers, friends, and relatives – especially when he acquires a gun and truly starts to live his fantasies.

1268.) This week a super-rarity on the show: A short fiction film made by the great documentarian/ethnographer Jean Rouch (a major influence on the New Wave filmmakers, due to his shooting handheld with low budgets on location). The film in question is called “Les Veuves de quinze ans” (the Widows of Fifteen Years), a 1964 character study of two teen girls who are in the “ye-ye” generation. They come from wealthy backgrounds but enjoy hanging out with their mildly flirtatious male friends at gigs by rockabilly sounding bands. The film precedes Godard’s Masculin-Feminin by two years and, although fictional, demonstrates Rouch’s way of exploring a milieu and letting his performers contribute to the storyline as it develops. It’s also another offering from the period of modern history that is a gift that keeps on giving and giving and giving…

1269.) My ongoing tribute to the more obscure work of teleplaywright extraordinaire Dennis Potter continues with a very personal work and a more experimental oddity. I start out with “Lay Down Your Arms” (1970), Potter’s first treatment of his time in the British Intelligence office, translating Russian documents. This program was part of Potter’s ongoing “autobiography,” spread out over a series of fictionalized teleplays that told us more about his life and behavior than any conventional autobiography would’ve. The second is the VERY weird “Shaggy Dog” (1968), a play about a job interview undertaken by a very OCD gentleman (John Neville, Gilliam’s “Baron Munchausen”). True to its title, the play involves a very prolonged, very silly joke, but it also focuses in on the way that job interviews serve as psychological “experiments” that reveal quite a lot about the interviewer as well as the interviewee. One knows the joke our hero is telling is not going to be a corker, but what we don’t know is how (and where) he’s going to deliver the punchline…

1270.) Returning to the topic of films you ain’t seein’ on TV anytime soon, this week I discuss and show scenes from Messidor (1979). The film is Alain Tanner’s portrait of two young women who meet while hitchhiking and then wander across the Swiss countryside, having been classified as criminals. These days, the film strikes one as being the original version of Thelma and Louise, but Messidor is a lot less romantic and glamorous, and deals with the realities of life on the road – where does one sleep? Where do you go to the bathroom? Where do you find money, and more importantly, who can you trust? Tanner uses a “leisurely” style of filmmaking, in which long takes and long shots stand in for flashcuts and dramatic close-ups. The two leads (Clémentine Amouroux and Catherine Rétoré) are terrific, playing women of 18 and 19 who think of of their unplanned trip as a “game” of endurance.

1271.) A very fun vintage episode, for the holiday (aired originally when Passover and Easter were also on the same weekend): Easter time is upon us once more, and so it’s the season for religious kitsch. This year I’m upping the ante, and instead of just mocking the (bountiful) kitsch spawned by Christianity, I’m aiming for a trifecta. First we’ll be seeing some images from a Scientology book that casts L. Ron Hubbard I a familiar light – lovely oil paintings of one of “the most popular writers of the 1930s” before he spawned a self-help philosophy that his followers (and the I.R.S.) deem a religion; in these black-velvet-worthy paintings he is seen rebelling against spiritual leaders, offering help to the helpless, and “putting things right” in the manner of Moses and Jesus and those guys. Next we move on to the granddaddy of biblio-centric religions, Judaism, and sample a little bit of a children’s video series intended to teach kids how much fun it is to study the Torah — and, yes, since it is kid’s entertainment, there’s a guy hamming it up as a villain and some really cheesy humor. From that point on, it’s back to familiar territory, as I run through a panoply of crucifix and Christ-adorned crap for kids’ parties. And then we travel straight to hell—in a Nigerian shot-on-video cautionary tale (involving a devil baby and demonic gay men!), and as interpreted by the late, great Ron Ormond in his masterfully creepy and over-the-top Estus Pirkle epic The Burning Hell (1974).

1272.) Continuing my series of episodes about the work of Dennis Potter, this week I discuss and show scenes from one of the most fascinating of Potter’s teleplays, “Double Dare” (1976). Produced when Potter was having a bout of writer’s block, the play works on several levels: as an exploration of writer’s block and how it affects the writer; as a work constructed around the blurred lines between the writer’s life and that of his creation; as a meditation on reality and art; and as another suitably playful yet tense discussion about the relationships between men and women. A teleplaywright meets an actress in a restaurant inside a hotel. They discuss a play he wants to write about a hooker and her client, to star the actress. As they talk, the action of the play occurs across the room from them, and they get lost in the world of the writer’s imagination…

1273.) Vintage: To commemorate the passing of actor/kiddie host/voice talent/nostalgia buff Chuck McCann, this week I re-air an episode created upon the death of a very different kind of celebrity, Linda Lovelace. Chuck was one of the many familiar TV faces who costarred in the very threadbare comedy Linda Lovelace for President (1975). The movie is Linda’s only “acting” appearance in a “legitimate” film. (There aren’t enough quotation marks to cover that sentence properly.) What is interesting for fans of McCann’s other work is that he plays an Italian-accented character he originated on his NYC kiddie show in the Sixties (escape artist “Bombo Dump” on the show) and later did in Harry Hurwitz’s “missing” indie comedy The Comeback Trail (shot from ’71-’79, released in ’82; see my blog entry about the film on the Funhouse blog) He is credited under two pseudonyms in the Lovelace film (which was, of course, R-rated), because he was simultaneously working on various kiddie shows and cartoons. The gents who did take onscreen credit include Vaughn Meader, Art Metrano, Joe E. Ross, Joey Forman, Scatman Crothers, and Micky Dolenz (!). As a bonus (and this is not a happy bonus), I briefly discuss Deep Throat, part II (1974), another R-rated film (which may or may not have had a more “adult” cut), this time a broad comedy directed by the “Bergman of softcore,” Joseph W. Sarno.

1274.) To salute the release of the first film by Alan Rudolph in 15 years (Ray Meets Helen, opening May 4), this week I discuss and shows scenes from one of Rudolph’s most underrated and underseen films, Remember My Name (1978). The film has never been released on DVD or VHS and has only been accessible via late-night cable showings. It’s a curious precursor to Fatal Attraction that is not a thriller nor a psychodrama – it starts out seeming like a suspense thriller but is actually a character study, and another of Rudolph’s quiet, moving statements on loneliness. The film stars two of the most tightly-wound actors in all of cinema (and the thinnest), Geraldine Chaplin and Anthony Perkins. Chaplin is stalking and taunting Perkins and his wife (played by Perkins’ real-life wife, Berry Berenson) while she works in a five-and-ten (with fellow cashier Alfre Woodard and under boss Jeff Goldblum). About two-thirds in Chaplin and Perkins have a dialogue scene that explains her behavior and completely, beautifully changes the way we feel about the characters. The film was produced by Rudolph’s mentor Robert Altman, but it shows the younger filmmaker forging his own style and moving away from imitating his friend/producer.

1275.) Vintage: In the third and last part of my interview with Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson, we talk about his primary cinematic influence (a certain Don Luis B.), his contemporaries (Kaurismaki, von Trier), and Ingmar Bergman, who was his instructor at film school (and not a nice one at that, according to Andersson). He also talks about his working methods on his features – how each film takes several years to complete. We go on to discuss Benny Andersson (no relation) from ABBA, who wrote the score for Roy’s first “new style” film in 2000, and close out with an informal, amusing exchange about (what else?) death.

1276.) Films made from the works of the great noir writers rarely capture their style and tone. One important exception, and a person fave of mine, is Serie Noire, the 1979 adaptation of the Jim Thompson novel Hell of a Woman by director Alain Corneau. The film beautifully captures Thompson’s semi-psychotic but also very straightforward tone by offering an extremely quiet character study that is punctuated by acts of violence (pop songs on AM radio provide the musical backing). Playing our con-artist, door-to-door-salesman hero is the amazing Patrick Dewaere, an actor who was perhaps the single best choice to play a Thompson lead (Bruce Dern runs a close second). Dewaere is nothing short of brilliant in his low-key work here, as a man who is capable of criminal acts but whose planning is most certainly going to blow up in his face. This is the first of two episodes I’m devoting to this film because it is so underseen and is indeed a heavy personal fave.

1277.) The second and final part of my tribute to the single best Jim Thompson film adaptation ever, Alain Corneau’s Serie Noire (1979). It’s a brilliantly quiet crime film/character study that features a knockout performance by the late, much-missed Patrick Dewaere. He plays a con-man, door-to-door salesman who decides to kill an old woman hiding plenty of cash in her house – and then run away with her niece, a quiet girl who has fallen for him. In this episode, I’ll be talking about the film, and then we go from the crime itself to the beautifully understated finale. (In which Corneau wonderfully solves the narrative problems posed by Thompson’s “paperback original” novel, A Hell of a Woman.)

1278.) Vintage: You may not know his name, but you know Howard Kaylan’s voice. He was the lead singer of the Turtles (where he sang the indelible, unforgettable “Happy Together”), had a short but productive stay in the Mothers of Invention, and then formed the genre-busting comedy-rock act “Flo and Eddie” with his friend and partner in parody Mark Volman. In the first of a few episodes I’m preparing from our interview, I speak to Howard this week about his recent memoir Shell Shocked and the reasons why he chose to write an autobiography at this moment in his life. We go on to discuss the immense popularity of the Turtles (including an extremely crazy “command” performance for Tricia Nixon at the White House – *every* detail would be different these days) and the search to find a follow-up to “Happy Together.” This culminated in the Turtles’ wittiest, catchiest slam at pop music (the wonderful “Elenore”). Also: Howard talks about memorable moments spent with the late, great Warren Zevon, whose songs were never giant hits for the Turtles, but who benefited quite a lot by one of their helpful decisions….

1279.) Vintage: The second part of my interview with the “rock raconteur,” Mr. Howard Kaylan, covers his years with Frank Zappa as co-lead vocalist (with his once and future partner Mark Volman) of the Mothers of Invention. Howard discusses the fine art of making Frank laugh before talking about the disciplined-yet-totally-random shooting of the film 200 Motels. He also speaks about the fine art of performing for “oldies” audiences these days and the reason why he and Mark became Flo and Eddie. Will Howard reveal the secret “groupie game” that Eric Burdon told him about? Tune in and see!

1280.) Given that the Mia Farrow and Woody Allen relationship never ceases to produce emotional “fallout,” I feel that it is the duty of the Funhouse to discuss this matter in a sincere and non-partisan way – by showing a over-the-top, melodramatic TV-movie about the case from 1995! Love and Betrayal: The Mia Farrow Story, directed by the amazing Karen Arthur (The Mafu Cage), is a version of the story told from Mia’s point of view (but including bits of info from Woody’s custody-bid as well). It’s a blissful telefilm overload, as we move through Mia and Woody’s relationship, with flashbacks to Mia’s prior life (in this episode, part one of two, it’s all about her “Charlie Brown,” Frank Sinatra). The most striking things about the film are how the characters seem to be living in a Woody Allen film (with them acting out scenes from his late ’70s and Mia-Eighties pictures) and how dedicated the two leads are to their roles. Patsy Kensit does a very good impression of Mia, while Dennis Boutsikaris does a “serious” version of Woody that is actually funnier than it would be if he were doing the standard imitation. Also: if you’ve ever wanted to see the infamous “taking nude photos of Soon-yi” and “little bastard” scenes acted out, you’re in luck!

1281.) The second and last part of my showcase for the over-the-top melodramatic telefilm Love and Betrayal: The Mia Farrrow Story. I discuss and show scenes from the film, which was directed by the amazing Karen Arthur (The Mafu Cage), who knows her way around overwrought melodramas. In this part of the proceedings, we reach the final break between Mia Farrow and Woody Allen (although he did still hang around the family a few times after having started an affair with Soon-yi). We then turn to the trial for custody of the kids that Woody had become the father of – but wonderfully punctuated with scenes from Mia’s earlier life. Herein are acted-out moments from her stay in India with the Beatles, her stealing Andre Previn away from Dory, and her short but eventful marriage to her “Charlie Brown,” Frank Sinatra. (At which point you will see one of my favorite all-time edits in any movie, during a sex-with-Frank scene.) The performers do their damnedest, and Patsy Kensit is indeed quite good as Mia. Dennis Boutsikaris essays a more serious Woody, albeit still a guy loaded with tics and odd gesticulations. It’s a helluva strange (and fun) movie.

1282.) I’m very proud to present the first part of my informal, friendly, and in-depth with filmmaker Alan Rudolph. The chat was done while Alan was in NYC to promote his latest film, RAY MEETS HELEN. The first film he’s made in 15 years, RAY is a beautifully rendered low-key, ultra-low-budgeted Rudolph movie – which means that film noir and screwball comedy are a part of the mix, as are absurdist dialogue and heartwrenching romance between misfits. In this part of the interview Alan talks about his attitude toward making films (“always the next one in your back pocket”), how he fared working for the first time with digital video on RAY, and the fate of an earlier film that never had a theatrical release, the wonderfully absurdist character study INVESTIGATING SEX (called INTIMATE AFFAIRS on DVD, 2001). Alan and I talked about his films (and those of his father, and the influence of his mentor/friend Robert Altman) for quite some time, so this is the first of a bunch of Rudolph episodes on the show.

1283.) Vintage: The third installment of my interview with Howard Kaylan is a very special one, in that we only briefly discuss the music business and instead talk about his favorite comedians. This is the kind of conversation I always *want* to have with my interview subjects (i.e., what they’re fans of), but usually jettison because of time constraints. We start out with closing remarks about Howard’s period in the Mothers, and then swiftly move on to a seminal childhood experience for him – his mother bringing him to a live taping of The Phil Silvers Show (“Bilko” to devotees everywhere). We next talk about his meetings with one of his biggest heroes, the great Stan Freberg, and move on to his good friend and bringer of truths, George Carlin. We close out with my favorite segment from our interview, Howard discussing getting high with the one and only Soupy Sales. The best part of this chat for me (besides the actual talk itself)? I got to sift through great footage of the abovementioned comedians to find appropriate clips with which to punctuate the interview. We return to discussions of pop and rock in the next part of my interview with Howard, but for now, it’s “Comedy Tonight!”

1284.) An all-time fave vintage episode: It’s been 16 years since I first presented the U.S. TV premiere of scenes from the oh-so-Sixties 1967 French telefilm Anna. The film is the only musical scored by Serge Gainsbourg, and it stars the radiant Anna Karina, “new wave” icon Jean-Claude Brialy, and Serge himself. The visuals are memorably pop-art-ish and the songs are equally indelible. Since the film has a super-simplistic plot and Gainsbourg’s lyrics are usually either poorly or all-too-rigidly translated from French to English, I was happy to present scenes from the film with French subtitles when I originally aired episodes devoted to it. In the time since, two all-too-rigidly translated English-subtitled versions of the film have appeared, so in this revamped episode (part one of two) I feature clips from the “version originale” plus one clip with English subtitles to show how Serge’s lyrical flourishes are completely lost in subtitling (and one clip with no subtitles at all so you can just dig the tune and enjoy Anna!). The film has never had a U.S. distributor, and so I am proud to present clips from it to remind Funhouse viewers how much fun it is.

1285.) Vintage: In the 16 years since I offered the U.S. TV premiere of scenes from the Serge Gainsbourg musical Anna, there have been no theatrical showings, no DVD, no airings on the indie cable channels (wait – there are none anymore!). Thus I thought it would be only fitting to re-air my original episodes, albeit with updated information. This week’s episode is the second part of my tribute to Anna, focusing on the film’s odd and oh-so-Sixties dream sequences. (English subs for the songs that truly need ’em and are subtitled accurately — one key screw-up in the translation of the ballad “Ne Dis Rien” makes it far better that its lyrics be viewed as French poetry.) In the second half of the episode I present some key Gainsbourg clips, including his own versions of songs from the Anna soundtrack. In a humidity-laden summer, there is nothing better than brilliant pop-rock music, and few people ever did it better than Serge.

1286.) As I turn “another year older and deeper in debt,” I discuss and show scenes from a film that I don’t think is very good, but I saw it at the right time (its initial release) in the right place (Paris) and have always had an infatuation for the lead actress in this, her latter-day “flapper” look. L’amour braque (1985) is an Eighties crime movie variation on Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, with plenty of random insane violence (guns, bombs, fire, stabbing, etc) and way too much intentionally odd melodrama. The film was directed by the master of melo-excess, Andrzej Zulawski, and remains watchable primarily for its female lead, Sophie Marceau, who graduated to “adult drama” with this deranged, high-key film. Marceau has become a better actress over the years, but her college-age appearance in this film is lovingly modeled after Louise Brooks and other 1920s stars. Zulawski was so smitten the two were married after the picture was made and they made three more films together (two of which I’ve seen, and are even more difficult to digest). Sophie is indeed the central reason to watch Braque – her and the random, weird violence amidst the goofy dialogue.

1285.) I’ve happily been sharing the lesser-known works of Dennis Potter over the past few years, and this week I’ll finally be talking about his work as a director. He only did it twice, and the first instance was Blackeyes (1989), a TV mini-series in which he explored sexism – his own and that of others. The plot involves a novelist who exploits his niece by fictionalizing her former experiences as a model. We see several different levels of reality and fiction: among them are the niece plotting her revenge against her uncle, the struggles of the model protagonist in the novel, and another character in the book who has taken control of the narrative from the uncle (and Potter). The film is most notable for having an anguished voiceover narration by Potter himself. He was indeed smitten with his lead actress (Gina Bellman) and also wanted to include reflections on one of his biggest traumas, having been molested as a child (the niece/ex-model character is a survivor of that trauma, and her uncle was the rapist). Blackeyes is a dense, emotionally wrenching, and not entirely successful work, but it still has the fingerprints of genius all over it.

1286.) In part two of my interview with filmmaker Alan Rudolph, Alan discusses Nick Nolte’s acting in four of his films (as both star and supporting player), and how Nick got Tuesday Weld to appear in Alan’s Investigating Sex (2001), her last screen role to date. We move on to talk about movie reviews and whether or not Alan reads or even cares about them, sparking memories of his first two mainstream films, both produced by Robert Altman.

1287.) Few American viewers have seen the two films directed by Dennis Potter, due to their having been slammed by critics on both sides of the Atlantic. This week I’ll be talking about the second thing he directed, his only theatrical feature. Secret Friends (1991) stars Alan Bates as an artist who suffers amnesia on a train ride. Like many of Potter’s protagonists, Bates’ character moves between realities – in this case, his real married life, his childhood (in which he had a “secret friend”), a fantasy game he and his wife have acted out (hooker/john), and a bunch of fantasies that involve his wife and his friend (and his friend’s wife). The film is uneven but contains some brilliantly emotional moments, and great performances from Bates, Gina Bellman (of Potter’s other film, the miniseries “Blackeyes,” and the later sitcom “Coupling”), and Frances Barber. Secret Friends is not for those who are unfamiliar with Potter’s other work, but it is a fascinating work for those who are already fans.

1288.) Vintage: In Part 4 of my very informal interview with the “rock raconteur,” Mr. Howard Kaylan, the front man of the Turtles (singer for the Mothers, “Eddie” of “Flo and…”), imparts his very honest feelings about the legend that was Lennon (loves the music, not as fond of the man); discusses at length a movie project that he and his partner Mark Volman were developing with scripter David Bowie (!); talks about the dynamics of being in a comedy team; and dispenses some of his deeply felt philosophy about getting into show business (and, more importantly, staying in the business). All of the above is illustrated with wonderful video clips (except the Bowie, I have no access to footage of Flo and Eddie and Bowie).

1289.) Vintage: The final installment of my interview with “rock raconteur” Howard Kaylan goes in some interesting directions. We discuss the “Flo and Eddie by the Fireside” radio show from the early Seventies, on which Howard and his partner Mark Volman interviewed rock royalty. Howard discusses why he’d never sanction commercial releases of the “Fireside” interviews and offers his opinions of the new phenomenon of concert-download sites (can anyone say “Wolfgang’s Vault”?). We go on to a little discussion of politics, and a bigger discussion of movies in which the Turtles’ music has been heard. Anytime I can discuss Wong Kar-Wai and Kaurismaki with a guy whose music I’ve loved for four decades, all is indeed right with the world….

1290.) Vintage: I start off a three-episode tribute to the immaculate, influential works of Jean-Pierre Melville with a show devoted to the four films he made that could easily be called “misfires” (discussion of his masterpieces will follow). I chose to go backwards in time to discuss these films and so I discuss his last film, Un Flic (1972) first, and then close out with the *extremely* rare film that is the most unlike anything else he ever made. Un Flic is a lopsided cop-and-crooks drama that stars Delon and Deneuve but gives the lions’ share of its running time to a master criminal (played by Richard Crenna!) carrying off a series of complicated heists. L’Ainé des Ferchaux (1963) is Melville’s Tennessee Williams’-esque tale of a broken-down boxer (Belmondo) who becomes the bodyguard for a corrupt banker (Charles Vanel); the two take a road trip across America and the banker’s interest in his young companion becomes obsessive. Two Men in Manhattan (1959) is a mess that contains some gorgeous NYC location shots and some wonderfully evocative scenes, but its plotting and acting are sub-par for the usually impeccable Melville. The last film under discussion is the torrid Quand Tu Liras Cette Lettre (1953), a “woman’s picture” that finds Melville making a movie purely for the money and turning out a rather crazed melodrama in which, among other things, a novice nun (Juliette Greco) forces a man who raped her sister to marry her (and then she, the nun, falls madly, insanely in love with him). It’s the most un-Melvillian thing you’ve ever seen, but that’s why it belongs in this celebration of the otherwise great moments in his four misfires.

1291.) The feast of St. Jerry occurs again this weekend (“Labor Day” to the rest of the country), and so the festivities commence on the Funhouse. First up is a discussion of Jerry’s death and the subsequent revelation of his disinheriting his first family – and the amazing fact that his first wife (whom he reportedly cheated out of alimony) is still alive and suffering dementia in a care facility. Then it’s on to a Funhouse discovery, a monograph in French on Jerry, written in Dec. 1964, when there was a celebration of the newly minted filmmaker’s first five films (and his being freed from his “handicap” – Dean Martin!). Then it’s time to talk about the auction of Jerry’s possessions – including many things with his logo on ’em, wonderfully crappy clown art, racist props, a stunning oil painting, and 73 (count ’em!) guns that Jerry owned. We close out with a fittingly artsy clip (one that begins in one direction and quickly flies in another). And thus is celebrated Joseph Levitch weekend….

1292.) Returning to one of the Funhouse deities this week, I discuss, and show scenes from, Chris Marker’s epic film essay Grin Without a Cat, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the rupture in time (and politics and culture) that was 1968. In the first of two episodes about the film, I cover “Fragile Hands,” the first half of Grin, in which Marker celebrates the positive political events of 1967 and then the explosion of early ’68, which included the riots in the Latin Quarter of Paris in May of that year. Marker assembled the film out of footage he, his colleagues from a filmmaking collective, and fellow filmmakers had shot around the world. Grin thus covers a lot of territory – from France to Cuba, the U.S. to Japan, and Chile to Prague. It’s a powerful work that finds one extremely talented filmmaker trying to “make sense of the Sixties” (in a far more effective and beautifully image-laden manner than, say, a PBS series with that exact title). It’s a film that Marker went back to and reworked over a span of 25 years, and thus it needs to be seen more. The Funhouse merely points the way….

1293.) The second and last part of my discussion of Chris Marker’s epic documentary Grin Without a Cat takes us to various locales post-1968. Marker called the second part of the film “Severed Hands,” and thus didn’t shy away from the depressing nature of the political situation around the world as the Sixties turned into the Seventies. The film is comprised of rarely-seen footage from many countries, all reinforced by a brilliantly written voiceover narration by Marker (delivered in English by a number of noted actors including Jim Broadbent). The film concludes on a sad but hopeful note, and stands as one of Marker’s great statements about politics and society.

1294.) It’s been decades since we supplied the American TV premiere of scenes from Anthony Newley’s wildly weird “8 ½” homage Can Heironymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe…? and it’s time once again to salute the only cabaret singer who also had desires to be Fellini, Chaplin, Marcel Marceau, and Pirandello. The last-mentioned is the key to the show saluted in this week’s episode, The Strange World of Gurney Slade. A 1960 British TV series that was well ahead of its time, Gurney Slade was devised by Newley and written by Sid Green and Dick Hills, two scripters better known for their work with Morecambe and Wise. The short-lived series, which deeply impressed a young David Bowie (who rhapsodized about it in a Ziggy-era interview), follows an Everyman who leaves the set of a staid, boring sitcom and then wanders around the British countryside – only to wind up in a courtroom debating whether he’s actually funny, and then confronting the characters in his series, who argue that they want to have lives outside the show. It’s a curious blend of numerous comedic modes (from Spike Milligan and Lewis Carroll to, yes, Pirnadello and other modernist playwrights) that may not be laugh-out-loud funny but it’s certainly imaginative and odd in a very endearing way (and prefigures later British reality-questioning classics like The Prisoner). Tony only sang once in the whole series, but Gurney Slade indicated he was operating at a whole different level from the other Vegas/West End song-and-dance men.

1295.) I’m very pleased to premiere scenes from “missing” movies on the Funhouse. This week I start a series of episodes about films by the great Finnish master of deadpan humor Aki Kaurismaki that have never been distributed in the U.S. The first film up I Hired a Contract Killer (1990), which ticks several boxes on the show because its star is French New Wave icon Jean-Pierre Leaud and its plot is a familiar noirish scenario (that I discuss at length and i.d. its original appearance in a novella by a very un-noir author). The film takes place in London, where the very quiet Leaud loses his job and then, being unable to commit suicide, hires a hit man to kill him. The hit man (busy British character actor Ken Colley) is a terminally ill “Samourai” (of the J-P Melville variety) who hunts for Leaud as the Frenchman moves through bars and eateries where gents like Joe Strummer (as himself) and Serge Reggiani (of the Melville camp) hang out. Contract Killer is a perfect B-picture of the old sort, but with a distinctly deadpan, quiet-as-anything approach to both humor and sentiment.

1296.) The third part of my interview with filmmaker Alan Rudolph moves informally through his directorial career. We start off with a discussion about the hostile critical reception that greeted his film adaptation of Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions. We then move backward (and forward) to discuss Keith Carradine’s many starring roles in his work, from Alan’s first “legit” well-budgeted feature, Welcome to L.A. (1976) to his return to moviemaking this year, Ray Meets Helen. The discussion moves quickly and loosely through the decades from first film to the “comeback” that will hopefully not be his last work behind the camera.

1297.) Another of the “lost” films by Aki Kaurismaki (read: no U.S. distributor), Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatjana is similar to Kaurismaki’s “Leningrad Cowboys” trilogy in that it is a “yokel comedy” about Finns on a road trip. The film stars AK’s two most recognizable stars, Kati Outinen and the late Matti Pellonpaa, and follows a “rocker” (Matti, in his last performance) and a coffee-addicted Mama’s Boy (Mato Valtonen) who drive around the countryside, escorting two Russian girls to their destinations. Beautifully free-floating in time, “Tatjana” is black and white and loaded with the things dearest to Kaurismaki’s heart – smoking, drinking, and listening to rock ’n’ roll. It also contains his trademark deadpan humor as well as his moving (and yet quite stoic) sentimentality. Plus, it illustrates quite wonderfully how *everyone* in society has someone else they can look down on….

1298.) Continuing my series of episodes devoted to the “lost” films (read: no U.S. distribution) of Finnish Funhouse favorite Aki Kaurismaki, this week I discuss and show scenes from one of his best-ever works, Drifting Clouds (1996). True to Kaurismaki’s style, it’s a low-key character study, filled to the brim with deadpan humor and a touching humanism, as well as a community of characters who smoke, drink, and listen to rock ’n’ roll. The film, which Kaurismaki said in a book-length interview is “about unemployment,” follows a maitre d’ (Kati Outinen) and her husband (Kari Väänänen) who lose their jobs at the same time and must find a road to new employment. The solution is a beautiful third act that is among the most touching passages in any of Aki’s works. Of all the films I’m showing in this quartet of episodes, “Drifting Clouds” was our biggest loss in the U.S. (It has played only in festivals of Kaurismaki and Finnish filmmakers’ work.)

1299.) Part one of the epochal Funhouse episodes in which I discussed the Ghoulardi phenomenon with Psychotronic zine innovator Michael Weldon. In the first show we talk about Ernie Anderson’s horror host alter-ego, a hip, sarcastic dude in a fake goatee who transfixed young and old alike in Cleveland for three years during the early Sixties. As Michael explains, the power of the program wasn’t just the character’s irreverent attitude or odd sartorial approach — it was also the cheesy Fifties horror pics he presented and the amazingly cool rock music played under his host segments. The two shows with Michael afforded me three fun opportunities: doing the host segments in tandem; editing the ultra-cool vintage local TV clips into the whole; and then encountering over the subsequent weeks (and years) transplanted Clevelanders who now live in NYC but never shed their memories of the man who told them to “Stay sick, turn blue!” when they were innocent youngsters.

1300.) Part two of my well-loved tribute from the year 2000 to Ghoulardi and the horror hosts of Cleveland finds cohost Michael Weldon, of Psychotronic Video, offering us insights into the weird situation that developed when Ernie Anderson left Cleveland in the mid-Sixties, and his “Ghoulardi” show spawned not one but three successors that all ran simultaneously for decades! Michael and I also explore the way in which non-Clevelanders encountered Anderson’s deep resonant tones in the Seventies and Eighties — doing movie trailers, and as the ever-present voice of ABC (“Saturday, on the Loooove Boat…”). You’ll also get a look at the last time Ernie played the Ghoulardi character (on Joe-Bob’s TMC show) and more vintage Sixties weirdness from the hepcat with the weird beard.