1353.) Part three of my ongoing tribute to the work of pioneering Czech filmmaker Vera Chytilova focuses solely on her 1980 chaos comedy Panelstory. The film revolves around the residents of a housing project that is going through massive renovations and being enlarged. Nothing works, everyone (including the inhabitants) get easily lost, and if the residents aren’t screwing each other, they’re being screwed by the management. Yes, it’s a comedy but it’s also a social satire that rates as one of Chytilova’s tighter films.

1354.) Providing an update of sorts on the work of the great British comedian Stewart Lee, I present the second and last episode discussing and showing scenes from his recent standup show “Content Provider.” In this part, Stew ponders being a collector in the age of the Internet, when everything a person wants or needs is available at the click of a mouse, and older diehard collectors and fetishists can muse about how difficult (and fun) it *used* to be to pursue your particular fascination. Stew’s show closes out with a modern twist on Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.” (It can happen.)

1355.) Going on a glorious tangent off the work of Jacques Rivette, this week I present a discussion of and scenes from the debut film by Argentinean filmmaker Eduardo de Gregorio, who co-scripted The Spider’s Stratagem with Bertolucci and Celine and Julie Go Boating for Rivette. The film discussed here, Surreal Estate (1976), is a sort of odd spin-off of Celine and Julie, as it finds stars Bulle Ogier and Marie-France Pisier in an old mansion that seems to be spawning its own narratives. Corin Redgrave stars as a blocked novelist who discovers the house and figures that he can write a novel about its occupants (including a dominant servant, played by Leslie Caron) – but soon finds that the house controls its denizens, rather than the other way around. de Gregorio made four later features, but this one is the most intriguing, as it deals with storytelling and sexuality, and is itself a sort of “hallway” running alongside Celine and Julie.

1356.) The second Pasolini film to be discussed in detail on the show is his 1969 act of subversion Porcile, aka “Pigsty.” It’s a bizarre and thoroughly transparent allegory, which interweaves two unrelated tales of unsavory practices. The first is cannibalism committed by a Spanish soldier (Pierre Clementi), which leads him to a confession that is the pivot of the end of the movie. The other plotline concerns the son (played by New Wave icon Jean-Pierre Leaud) of a German businessman who makes money off of pigs (in case you don’t get the metaphorical level, he sports a Hitler mustache). The businessman is visited by a sympathetic friend, played by Funhouse favorite Marco Ferreri; those two are then joined by a rival businessman (played by the great Ugo Tognazzi), as the errant, rather perverted son rejects his socialist protester girlfriend (played by Leaud’s partner in Godardian frenzy, Anne Wiazemsky).

1357.) The first of two episodes about Italian avant-garde filmmaker Carmelo Bene. A contemporary and colleague of Pasolini, Bene was first and foremost a theater director and playwright, but for a handful of years in that most turbulent of times (’68-’73) he made a handful of movies. They are colorful and crazy, alternately profound and ridiculous, and feature moments of visual beauty and rather goofy shtick. His influences encompassed various theatrical artists and also American underground filmmakers (most notably Anger and Jack Smith) and Funhouse deity, Uncle Jean. In this episode I discuss and shows scenes from three of his features: Our Lady of the Turks (1968), an overlong episodic work that introduced his experimental style; Capricci (1969), an off-the-rails provocation that costars Godard perennial Anne Wiazemsky; and One Hamlet Less (1973), his warped and truly gorgeous-looking adaptation of Shakespeare’s classic.

1358.) All the classic Xmas movies have been shown and reshown countless times, so much so that it’s time to explore the underside of Yuletide moviemaking. That underside is surely represented by the 1989 straight-to-vid horror movie Elves starring TV’s “Grizzly Adams,” Dan Haggerty. The picture starts out in a tongue-in-cheek mode and its plot is surely the stuff of classic trash past – a washed-up police detective turned department store Santa uncovers a hideous Nazi plan to mate women with elves to create the Master Race. There’s a bit more to it than that – including the fact that the girl who is the frontrunner for the task is the product of a union between her grandfather and her mother, and that it’s never explained why there’s only one goddamned elf (looking more like a troll) in the whole movie. Although it starts out on a light note, Elves gets more sincere about its insanity as it moves on and gets unpredictably odder and odder. The final “kicker” you’ve seen before but not quite in this kind of… er, package. (with a bow on the top and an elf on the wrapping)

1359.) Vintage, to commemorate Anna’s passing: It’s been 17 years since I first presented the U.S. TV premiere of scenes from the oh-so-Sixties 1967 French telefilm Anna. The film is the only musical scored by Serge Gainsbourg, and it stars the radiant Anna Karina, “new wave” icon Jean-Claude Brialy, and Serge himself. The visuals are memorably pop-art-ish and the songs are equally indelible. Since the film has a super-simplistic plot and Gainsbourg’s lyrics are usually either poorly or all-too-rigidly translated from French to English, I was happy to present scenes from the film with French subtitles when I originally aired episodes devoted to it. In the time since, two all-too-rigidly translated English-subtitled versions of the film have appeared, so in this revamped episode (part one of two) I feature clips from the “version originale” plus one clip with English subtitles to show how Serge’s lyrical flourishes are completely lost in subtitling (and one clip with no subtitles at all so you can just dig the tune and enjoy Anna!). The film has never had a U.S. distributor, and so I am proud to present clips from it to remind Funhouse viewers how much fun it is.

1360.) Vintage favorite, presented to commemorate the death of Anna Karina: In the 17 years since I offered the U.S. TV premiere of scenes from the Serge Gainsbourg musical Anna, there have been no theatrical showings, no DVD, no airings on the indie cable channels (wait – there aren’t any anymore!). Thus I thought it would be only fitting to re-air my original episodes, albeit with updated information. This week’s episode is the second part of my tribute to Anna, focusing on the film’s odd and oh-so-Sixties dream sequences. (English subs for the songs that truly need ’em and are subtitled accurately — one key screw-up in the translation of the ballad “Ne Dis Rien” makes it far better that its lyrics be viewed as French poetry.) In the second half of the episode I present some key Gainsbourg clips, including his own versions of songs from the Anna soundtrack.

1361.) The second and last part of my tribute to Italian avant-garde filmmaker Carmelo Bene. This show is devoted entirely to his Salome (1972), a visually arresting adaptation of the Oscar Wilde play that also harkens back to its Biblical subject matter. Bene was a noted figure in Italian theater and so his films were rife with theatrical conceits, but he was also clearly a student of both Godard and the American underground, so his films have *bright* primary colors, jarring editing, gorgeously artificial sets, and many naked bodies. This particular feature contains ample amounts of classical drama and outlandish comedy (John the Baptist is an older thin, yelling Italian guy being hit in the head by a holy book). Bene avoided using conventionally known actors in his films but here he has two internationally famous models in the cast – Veruschka (Blow-Up, the recent Casino Royale) and Luna (Skidoo, Satyricon). The film’s best sequences deal with John the Baptist’s friend Jesus attempting to crucify himself and finding out that it’s not as easy as it looks….

1362.) In honor of the death of Buck Henry, I present a very special “strange arthouse artifact” episode. The topic of discussion for this episode, with ample amounts of footage, is the 1972 Yugoslavian short “I Miss Sonia Henie,” which is a series of short vignettes directed by a group of internationally famous filmmakers who were gathered for the Belgrade Film Festival. I will also be showing scenes from a documentary made about the making of the short (!). Among those who contributed bits to the short are Dusan Makavejev, Paul Morrissey, Frederick Wiseman (scripting and directing a fiction film, something he did only twice thereafter), and Buck Henry and Milos Forman who had just made Taking Off and were promoting the film overseas. “Sonia Henie” was an experiment in form (and sexy silliness) in which the participants had to shoot a three-minute vignette in one small apartment, with no camera movement or tricky framing or editing (and, needless to say, with a very small cast). And somewhere in whatever brief sketch that was written had to be the line “I miss Sonia Henie.” (1972 was still technically the Sixties, esp. in international cinema, kiddies….) The result is, of course, a rather wacky mixture of sexual liberation and off-kilter humor, which is “completed” by the Henry/Forman sketch, which finds an inventive way of getting the signature line of dialogue into the proceedings.

1363.) In the realm of “low trash,” there are few truly stunningly clueless auteurs. One of the “greatest” in this regard was Doris Wishman, a woman who spent her time making sexploitation films that weren’t sexy, nor were they coherent. And so, I present on the show a discussion of, and scenes from, her penultimate movie, a truly gonzo piece of unsexy what-have-you called Dildo Heaven (2002). The movie is a video shot in her adopted home state of Florida that finds three women trying to date their bosses. (Doris’s scripts were frozen in the Sixties.) While doing this, we also see a guy who lives in their building, a nerdy young man, peeking into the keyholes of the other residents of their apartment complex – as in her famed Keyholes Are for Peeping, this allowed Doris to intercut scenes from her other movies, or from more competently shot items that she acquired the rights to (or were in public domain, so who cared?). The video is truly one of a kind – so much so that all copies of it that show up on the open market have a “For Screening Purposes Only” disclaimer on them. Certain things in the universe are a constant, and it’s nice to know that Doris Wishman’s unskilled and bizarre approach to moviemaking (shoot the feet, shoot the phones, shoot the wall hangings, get a reaction shot from a pet or a stuffed animal) was one of those constants.

1364.) The third and last of my tributes to the cult British TV series “Rock Follies.” This time out I’m discussing and showing scenes from the second (final) season, called “Rock Follies of ’77.” The show truly jumped the shark in this season, but there are still things to be enjoyed. The plot chronicles the fragmentation of the show’s trio of women singers, but the songs (with catchy melodies by Roxy Music’s Andy Mackay) are memorable, as are the lead performances – although rock belter Julie Covington was fast becoming the show’s star and the other two “Little Ladies” were left in her wake (both in the plot and on the show). Although the first season was very popular on PBS, this season wound up not being played until the late 1980s because of “raunchy” plot elements, which would scarcely raise an eyebrow today. The element that will please current American viewers are the guest stars: Tim Curry steals one episode as a terrific would-be UK Springsteen or Lou Reed (read: a phony ex-gang member/performer who’s “a poet of the streets”), and Tim’s RHPS costar Little Nell and the soon-to-be-famous Bob Hoskins are memorable supporting players.

1365.) Part four of my tribute to cult Czech filmmaker Vera Chytilova focuses on her collaborations with the actor Bolek Polívka, who coscripted as well as starred in certain of Chytilova’s films. The first film discussed is the amazingly titled The Inheritance, or fuckoffguysgoodday (that’s its real title, 1992). It’s a yokel comedy that is a minor work by Chytilova but was a big hit in its afterlife on video and on television. The “feature presentation” of this episode is The Jester and the Queen (1988), which is a fascinating comedy-drama in which the groundskeeper of a castle (being used as a summer hunting lodge) imagines that he and visitor knew each other in another life – she as a queen, he as her court jester. The film is a gorgeously shot character study/fantasy that is simultaneously about class, sexual domination, fantasy, and memory; unlike The Inheritance, it’s most definitely a major work by Chytilova.

1366.) I am very proud to present a Deceased Artiste tribute to a Funhouse favorite and an interview subject as well, the great “comedian’s comedian” Chris Rush. I interviewed Chris in 2010 but wasn’t able to dig up any older footage of him at the time. (He died in January of 2018.) This week’s episode, part 1 of two, rectifies that with wonderful bits from his appearances on television (which didn’t occur at regular intervals) in the 1970s and ’80s. I start off with some of Chris talking in Seventies interviews on local programs, and then we include some standup footage – from an appearance on “Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert” (in September 1979, doing his bits on TV and drugs, because the rest of his catalogue was too salty for network TV) and an uncensored gig in the early Eighties. Chris was a really nice guy and a naturally funny gent whose conversations went by at a fast clip, with footnotes, sidelines, and wonderful observations – much like his best routines (and his final one-man show – for that, catch part 2….).

1367.) The second and last part of my Deceased Artiste for the late, great Chris Rush, who died in early 2018, but lives on in the Funhouse. Chris was a terrific standup who was a “comedian’s comedian,” admired by his fellow comics (two of whom – George Carlin and Tim Allen – produced his one-man show, Bliss). This episode focuses mostly on clips from a rare recording of his Bliss show, done at the Record Collector store in Bordentown, N.J. in 2010. In this performance Chris moved through the Bliss material and some older bits, combining his original comic topics (NYC behavior, TV viewing, drugs) with his later fascination, namely quantum physics and how it related to both spirituality and our everyday behavior. Chris was a great comedian and a really nice guy, so I am very pleased that we can pay tribute to his memory on the show in the only way he’d have wanted – by sharing his comedy.

1368.) The fifth episode in my series of shows saluting the work of cult Czech New Wave filmmaker Vera Chytilova covers just one of her works, perhaps the darkest one of all. Like a few other of her later features, Traps (1998) has two different “tones,” in that it starts out as a discomforting farce and then turns into a nightmarish social satire. The plot moves into gear when our heroine (a veterinarian, a profession that figures in the movement of storyline) is raped by a smug low-level politician, aided by a playboy ad exec. The rape victim is not a passive character, though – she quickly enacts a plan to (veterinarian knowledge kicks in here) drug and castrate the rapists. At this point the film still has the tone of a disturbing farce, with the men attempting to deal with their “dilemma” in various ways. But it soon turns into the film you initially thought it would be – a stark character study that shows how the privileged can conceal their crimes, and the working class deal with the aftermath of the same crimes. The second half of the film serves as a pitch dark depiction of a woman who endures the trauma and shame of the rape, while also discovering that the few people on her side will gladly sell her out. Chytilova didn’t cut corners – she wanted to elicit conventional emotions from her audience, but also to disturb (and amuse); Traps is one of the farthest journeys in that direction.

1369.) Returning to the “you ain’t seein’ this anyplace else” department, this week I discuss and show scenes from Alain Resnais’ MIA film La guerre est finie (aka The War Is Over, 1966). Out of print for on DVD for a while now (and the copy you can buy used looks good but comes from Brandon Films – remember them, HS film nerds?) and rarely shown in repertory, Guerre is a beautifully realized political work that qualifies as a fine drama, a thriller, and a love story; the script by real-life Spanish Communist freedom fighter Jorge Semprun (who later scripted Costa-Gavras’ breakthrough political thrillers) melds perfectly with the time-slip direction of montage-master Resnais. Yves Montand stars as a Spanish Communist who is journeying to and from Spain from France and is encountering resistance both from the party chiefs (who are doctrinaire and favoring slow, incremental actions) and the young lions of the party (who want explosions and terrorist incidents right away). It’s a beautifully constructed film with much care put into the camerawork, editing, and music, as well as the performances – Montand is ably supported by a great collection of actors, including Ingrid Thulin as his steady partner and young Genevieve Bujold as his sometime-lover.

1370.) Returning to the off-kilter world of Doris Wishman, I salute her final film, a “thriller” called Each Time I Kill. As was always the case with Wishman’s work, the film was made on a shoestring and it makes no sense. Although (also true of Doris’ early films) it’s densely plotted for a no-budget feature. Here the heroine is a nerdy, ugly young woman (read: actress in ugly makeup and wig) who discovers a locket with instructions – each time she kills someone, she has to recite an incantation and she will receive their best asset (hair, teeth, bosom, etc). The visuals are classic Doris (feet, things on the wall, mismatched countershots) but the guest-star aspect is new – Fred Schneider (yes, he came from Planet Claire) plays the girl’s father and John Waters does a cameo as an “amused horror movie viewer.” Doris died while the film was being shot, and the credits reveal that Joe Sarno, another Funhouse favorite finished up the shooting (making the results look uncannily like one of Doris’ films, not his). It’s a good note for her to have gone out on, because it’s as absurd and bizarre as her Sixties and Seventies films were.

1371.) I revisit the joy that is Funhouse favorite George Kuchar through the vehicle of his wonderfully talented student Curt McDowell, who asked George to script his first feature film – and out popped Thundercrack! I’ve talked about this amazing 1975 cult/underground/camp/porn/horror/comedy/act of subversion a few times before on the Funhouse but this time out I’m discussing not only the film itself but the supplements that are present on the Synapse Blu-ray of the film (yes, it was all cleaned-up for High Def video!). Thus, I will talking about the production of the film, its strange schizo nature (in which McDowell’s subversive underground tendencies and ambi-sexual plot twists are counterpointed by Kuchar’s love of old movies and his taste for ripe dialogue and lurid plot twists), and its place in cult movie history, as well as showing bits from the George-narrated trailer, outtakes, a rare interview with McDowell and star Marion Eaton (without her oddly drawn-on eyebrows), and a rarely shown McDowell short made shortly before the commencement of the brilliance and craziness that was (and is) Thundercrack!

1372.) The “kitchen sink” cycle of films is supposed to have officially died with Lindsay Anderson’s collaborations with Malcolm McDowell, but the feature I’m discussing this week, Little Malcolm and his Struggle Against the Eunuchs (1974), definitely has major connections with the kitchen sink/angry young dramas. Basically a filmed play (“opened up” for cinema), it tells the story of an art student (a young and shaggy John Hurt) who, out of sheer spite, begins a political party with his friends, the ridiculously titled “Dynamic Erection” party. He espouses a political philosophy, but mostly the party is created to get back at a fellow art student who had him kicked out of a pub. The film starts out as a comic satire (with very funny comic dialogue, from the play by David Haliwell, and a great supporting performance by David Warner) and slowly becomes pitch dark, since Malcolm’s political impulses, such as they are, are completely fascist. Little Malcolm was out of distribution for decades, since it was included in the wrangle between its producer – a certain George Harrison (who contributed a song to the soundtrack and produced two others) – and the late, not-so-lamented Allen Klein. Harrison bankrolled the film as he did with later “Handmade” titles, because he had loved Halliwell’s play and wanted to see a movie based on it.

1373.) Since I make a concerted effort to show Christian kitsch on Easter weekend, I thought I’d let the “other side” speak for once, with a discussion of, and scenes from, Ermanno Olmi’s wonderful drama The Cardboard Village (2011). Olmi, best known for The Tree of Wooden Clogs, was a lifelong Catholic whose later work went in many directions, with one of the most interesting being his use of Neo-realist techniques (most notably using non-professionals as actors) to present allegorical tales of faith and doubt. Here he features professionals in two key roles – the sublimely talented Michael Lonsdale plays the lead, a priest whose church is being demolished. As the old Father is dealing with that, a group of African immigrants find refuge in the church and create the titular “village” inside it. The film raises many issues about religion, including the old classic “shouldn’t houses of worship provide space to the homeless and refugees?” Olmi explores this issue from the perspective of the immigrants, Lonsdale’s character, and another priest who feels the old church must be destroyed (played by Rutger Hauer, the star of Olmi’s superb Legend of the Holy Drinker, already presented on the Funhouse). The film is a quiet, subdued character study of the kind Olmi did best; made when he was 80 years old, Cardboard Village looks to both the past and the future of Europe and the Church.

1374.) The annual Easter showing of cwazy kwistian crap takes place once more, with a “message drama” intended for reverent Christians and right-wing folk as well. This time out, it’s God’s Not Dead 2 (2016), a delightfully awful (delightful in the fashion I am presenting it) tale of a teacher (Melissa Joan Hart) who gets into hot water for discussing the joys of Jesus in her classroom. The film is part of a singular franchise that gets into the “organized persecution” of Xtians in the U.S. with fictional trials at the center of each film – and casts of prominent right-wing MAGA supporters, as well as actors who just need a job (they usually play the “evil atheist” villains). In this instance, the former network TV “Sabrina” is supported by Robin Givens and Ernie (Ghostbusters) Hudson), as well as guest stars Mike Huckabee (as himself) and big-time “sanitizer” of rhythm and blues, Pat Boone (as Hart’s dad). The film, directed by a person named “Harold Cronk,” has the feel of an over-budgeted Hallmark movie, with a *lot* of plot, including an entire unnecessary subplot, giving the producer (David A.R. Wright) a prominent role – but he isn’t the single best cast member. That would most certainly be Ray Wise, the wonderful character actor who is best known for playing Leland Palmer/“Bob” in iterations of “Twin Peaks.” The very talented Wise is the atheist villain here (a prosecuting attorney who wants to crush and humiliate our heroine), and he is the shining light in this brightly lit but ridiculous courtroom drama.

1375.) A return to a film that has been very rarely shown in theaters but deserves greater attention. Paul Morrissey’s Forty Deuce (1982) is a filmed play that Morrissey and his cameramen (who included Orson and Market collaborator Francois Reichenbach) “opened up” by setting some scenes in real NYC locations, providing us with incredible views of the titular street of many movie theaters, as well as the surrounding environs in Times Square and Hell’s Kitchen. The second half of the film is even trippier, as it employs split screen in an interesting fashion – to show different angles of things occurring in the same room. I’m discussing and showing scenes from the film to honor two gents who recently joined the Deceased Artiste roster, Orson Bean (who got lead billing and gives a very good supporting performance as the well-off patron of a bunch of male street hustlers) and Manu Dibango, who supplied the soundtrack.

1376.) Airing as this episode does during the quarantine for the coronavirus, I could find no better oddball stuck-inside entertainment (although the host segment for the episode was shot about four months back). This week’s film under discussion is Paul Bartel’s “lost” 1993 comedy Shelf Life. Essentially a stylized filmed play, the picture revolves around three siblings who were locked by their parents inside a fallout shelter on Nov. 22, 1963. “Thirty years later and forty feet under” (as an onscreen title proclaims) we join them as adults who have an average day engaging in games, playing roles, and being both endearing and abrasive. The three actors who star in the film wrote the original play and the emphasis on odd rituals and ceremonies is the film’s most unusual aspect; the color filters that Bartel and his crew used to stylize the action are the most eye-catching element of the visuals. The living participants are trying to get the film restored at this time, so perhaps it will see an official release… in time for the next quarantine?

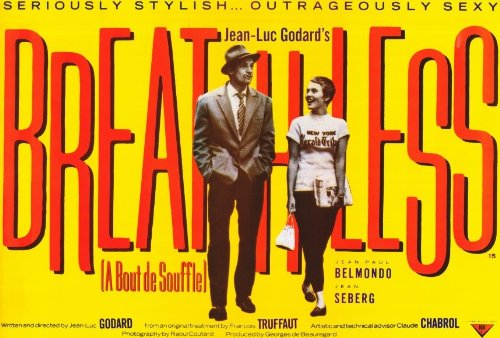

1377.) I take great joy in celebrating the careers of those departed whose work I loved, and so this week I present part one of my two-part Deceased Artiste tribute to Anna Karina. This episode covers the more familiar titles – but, as always in the Funhouse, I have added a title that very rarely plays in the U.S. The films you have should have heard of include her features (and one short) with her first husband, Funhouse fave “Uncle Jean,” aka Jean-Luc Godard. From 1960’s Le Petit Soldat (where Anna is so adorable she is subject of a bet as to whether the lead character will fall in love with her upon a mere look at her) to 1966’s Made in USA, Anna was Godard’s muse and frequent lead actress. I show scenes from the films they made together, most notably the masterworks Vivre Sa Vie and Pierrot Le Fou, but also spotlight a film that isn’t all that great, but in which she was (as always) luminous. The picture in question is Ce soir ou jamais (Tonight or Never), a stagey 1961 romantic comedy with Anna as the girlfriend of a pretentious theater director. The film is minor, but Deville mimicked Godard (and some other classic auteurs) by having the characters speak directly to the camera and he did block off a segment for Anna to do a frenzied dance with a male character in a party scene.

1378.) The second and last part of my Deceased Artiste tribute to Anna Karina focuses on the post-Godard years when she was an actress-for-hire, appearing in an array of weird misfire pictures funded by U.S. and U.K. studios, and her first directorial effort (one of only two she made as writer-director). We start off with a discussion of, and scenes, from the post-’67 films that are jarringly misguided but have big-name casts and seem like they could have (possibly) been good if better thought out (The Magus, Laughter in the Dark, Justine). We move on to Anna’s own film, Vivre Ensemble (Living Together) from 1973. The film follows a troubled relationship, filled with substance abuse and jovial but directionless behavior, that takes place in Paris and Manhattan. I will be giving the American TV audience the first look at the NYC-shot scenes, which are mostly in English or feature little dialogue. Anna and her male lead visit Central Park (during an anti-war rally), stay in an apartment in Harlem (thus affording us a view of 125th St), meet friends at the Metropolitan Museum, and go out for a bite to eat downtown (after wandering on the Deuce) in fascinating “wandering” sequences. Vivre doesn’t cohere as a film because the stormy relationship at its center seems destined to fail and is comprised of giddily-happy scenes followed by tragic ones. But Anna’s radiance as a performer and her choice of locations for the doomed-to-fail relationship make the film worth watching, and saluting on the Funhouse.

1379.) It’s been a while since I’ve tackled the topic of little people in the media. In this episode I discuss, and show scenes, from a terrific documentary called The Search for Weng Weng. The film follows Australian film fan and historian Andrew Leavold as he searches for information about the tiny (2’9”) Filipino star Weng Weng, whose two (surviving) James Bond spoof movies have garnered a cult around the world. What Leavold discovers is basically the history of the “Pinoy action film” as it existed in the Sixties and Seventies, and also the story of Weng Weng (real name: Ernesto de la Cruz) and his rise to fame as the star of a series of comedy action movies and subsequent return to the poverty that he was born into. Along the way Leavold provides us with fascinating glimpses at both the films and the stars and directors who made them, as well as the sad but instructive story of Double-Weng, a small man who left a giant imprint. (And if that’s not enough for ya, there’s a subplot about Leavold meeting Imelda Marcos in her retirement palace!)

1380.) Vintage, to commemorate the death of Michel Piccoli: A wonderfully bizarro film like no other, Themroc is a study in personal revolution. The adventuresome Michel Piccoli plays the lead character, a grunting, yelling worker (the whole film is in a made-up language that has a little – but not much – to do with French) who goes mad one day. He is fired from his job, so he goes home, sleeps with his sister, bricks up the door to his room, bashes a hole in the wall leading out to a courtyard, tosses furniture out the newfound hole, repels the cops (even roasting and eating one), and then has a mindblowing orgy (including the great Patrick Dewaere in one of his first “adult” roles), because, you know, that’s what you do. A product of the Sixties (although made in ’73, which is still the Sixties), Themroc is an amazingly brazen act of provocation that defies laws of logic, language, and linearity. It’s nuts and proud to be so.

1381.) One of the most fascinating culture-clash creations I’ve watched in the last few years is the subject of the show this week. The film in question is Topo Gigio and the Missile War, a 1967 vehicle for the renowned Italian mouse-puppet that entertained kids in Europe, America (most notably on The Ed Sullivan Show – “give me a kiss, Eddie…”), and with incredible success in more recent decades in Latin America. The Missile War film was an authorized “adventure of the character (by the puppeteer who created him, Maria Perego, who recently died at 95), but with a major twist – it was made in Japan by the much-lauded filmmaker Kon Ichikawa (Fires on the Plain, The Burmese Harp, Tokyo Olympiad)! Ichikawa tackled the subject by making a very minimalist film (jet black backgrounds with characters and objects in primary colors, giving the film an oddly Sixties/JLG look). The plot is derived from an Italian caper film (namechecked in this film, twice) about a gang of crooks trying to break into a bank from a nearby prison. Of course, in this instance the friendly but sleep-obsessed Topo stumbles onto the robbery and ends up foiling it. In the course of matters he falls in love with a red balloon. As is often the case with items from the Sixties (that period that “keeps on giving and giving and giving…”), you have to see it to believe it was ever made.

1382.) In the much-loved realm of low trash, the clueless filmmaker is sacred. There are the icons of cluelessness (Ed Wood, Doris Wishman) and there are the modern practitioners (Tommy Wiseau, Neil Breen, the guy who made Birdemic, et al). It’s always nice to find another person who doesn’t really know or care about continuity, structure, technical rules of camerawork/framing/editing, and of course screenwriting but still takes it upon themselves to make a feature film. Such a man was “John S. Rad” (real name: Jahangir Salehi Yeganehrad) who made the remarkably incoherent Dangerous Men (released in ‘85, then retooled for decades and re-released in 2005). Rad was an Iranian who reportedly made films in his homeland, but his American debut is a stunning work of parallel storylines that take many weird detours. The plot, such as it is, concerns the death of a man that is being avenged by both his cop brother and also by his fiancee, who takes the more interesting path – flirting with random men whom she will later kill. The added-on characters takes the film in different unexpected directions, with the best part being that the final protagonist is a drug-dealer character we only see for the last few scenes in the picture and thus are not even certain why he’s in it in the first place. (He’s actually related to a character who died long before.) Dangerous Men is terrible but it’s the kind of terrible that is compulsively watchable.

1383.) To salute me turning “another year older and deeper in debt,” I present a fun film that has seemingly gotten lost in the shuffle of TCM/DVD/streaming (it’s out there, but not too often shown or reviewed). The picture in question is Champagne for Caesar, a 1950 comedy that spoofs game shows and Americans’ perception of intellectuals. An aged Ronald Coleman stars as an “egghead” who loathes TV quiz shows, so he appears on one in order to bankrupt it (him being a walking encyclopedia and all). In the process, he alarms the show’s sponsor, played by Funhouse deity Vincent Price. Price’s character wants to ruin his intellectual nemesis, so he hires a spy (Celeste Holm, quite an odd choice as a bombshell) to find out Coleman’s Achilles’ heel as a Brainiac. The result is a silly film that is quite entertaining and fascinating as a slice of TV history – since radio was still hanging on in ’50 but was rather rapidly being usurped by television. Imagine a world where a woman could fall for Art Linkletter (who plays the goofy host of the game show, beloved by Coleman’s sister) and you have the screwball universe of Champagne for Caesar.

1384.) Returning to the old topic of “things too good for BBC-America,” this week on the show I present oddities from the British DVD releases of Stewart Lee’s BBC work. The first are scenes from the unexpurgated interview/interrogation of Stew done by Chris Morris for the third season of “Stewart Lee’s Comedy Vehicle.” After Stew’s act is analyzed, dissected, and derided, we look at some scenes from a work-in-progress version of his last show Content Provider, done at a small club and including bits he didn’t keep in the final show.

1385.) There’s never an “expiration date” on doing Deceased Artiste tributes in the Funhouse, and so this week I’m saluting Marshall Efron, who died many months ago. In this episode, I discuss his career with the focus on the absolutely wonderful Seventies children’s show “Marshall Efron’s Illustrated, Simplified and Painless Sunday School” (1973-78). Efron co-created the show with his writing partner Alfa-Betty Olsen, and he was the entire cast – a one-man collection of odd yet adorable characters from the Old and New Testaments (and some that were just made up to fit into the framework of the parables). The show was focused on the storytelling aspect of the Bible (as both Efron and Olsen were cited in “TV Guide” as being “not pious”), and it was the single best way to take in these tales when one was a kid back in the Nixon/Carter era. In various makeup jobs and costumes, Efron told the tales in an informal (but still accurate) way, aided by mannequins, dolls, stock footage, drawings, and (then) state-of-the-art video effects. The “Painless Sunday School” has sadly slipped through the cracks of TV history in terms of reruns and DVD releases, but its memory remains strong to to those of us who saw it at the right moment (and posted some episodes on YT, as this former Catholic-school-student-turned-Atheist did when Efron died at the end of 2019).

1386.) Jean-Luc Godard is a Funhouse deity, and so this week I return to the well with a presentation of one of his finest shorts in mine ’umble opinion. “La Puissance de la Parole” (The Power of Words, 1988) is a beautiful short film that interpolates two narrative strands, both of which are powerfully emotional and both of which contain dialogue by a great, long-gone American author. One narrative depicts two gods (here seen as an older man and a younger woman out for a drive) having a conversation – from a short Poe text called “The Power of Words.” The other depicts a phone call between a couple that has broken up – with dialogue taken from The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain. Godard blends these two narrative strands with a variety of music and absolutely radiant imagery, for one of his finest but least-known shorts.

1387.) This week in the “Consumer Guide” department, I return to the wonderful output of the Welsh DVD company (read: downloads, live streams, etc) Go Faster Stripe. In this instance, I review the latest performance videos from two of the UK’s finest comics (neither of whom is well known over here – it’s our loss). The first is The Wreath by Simon Munnery, the man who gave us, “Attention, Scum!” (one of my favorite Funhouse offerings, which divided viewers – always a good sign). Munnery’s latest is a diary-like recounting of his middle-age existence, including a new joke he came up with (that he turned into a short film and an oil painting! Not forgetting the postcard of the oil painting…). He also discusses working at a minimum-wage cleaning job where his innovative ways of cleaning were never enough for his bosses. From the Munnery we turn to Mark Thomas, a brilliant political comedian/one-man show whose show Check-up: Our NHS @ 70 celebrates England’s National Health in amusing and touching detail, along with a discussion of the politicians who are chipping away it, trying to privatize and/or eliminate various parts of its service. Mark investigated the NHS in a number of ways, including following around various doctors and nurses as they dealt with emergencies and – in perhaps the funniest and most pertinent element for middle-aged viewers – asked his own general practitioner to describe what could happen to him medically as he decays into old age….

1388.) A discussion of the great (and under-appreciated) New German Cinema filmmaker Werner Schroeter, through the vehicle of the documentary Mondo Lux (2012), which was made by his cinematographer Elfi Mikesch when Schroeter was stricken with cancer but also preparing his last film, his last theatrical production, and a gallery show of his photographs. Mikesch captured the essence of Schroeter, the man and the artist, through his own reflections, film clips from his films, and interviews with his collaborators and friends. The last-mentioned include Isabelle Huppert, Ingrid Caven, and Funhouse interview subjects Wim Wenders and Rosa von Praunheim. The documentary offers a “101” look at Schroeter’s work and his life, which though he described himself as “lazy,” was filled with artistic endeavors and appreciation.

1389.) This week I salute a special, unseen-in-decades program for two reasons: because it serves as tribute to the late, great music producer Hal Willner, whose legacies of music production in the studio and onstage are very, very strong, especially here in NYC; and also because it is sublime. The show in question is an outgrowth of Willner’s “Lost in the Stars” Kurt Weill tribute LP entitled September Songs: The Music of Kurt Weill, co-produced by Canadian, Portuguese, and German networks. The show features performances of songs from different periods in Weill’s career, punctuated by historical material about Weill’s career and life. The performers are ideally suited for the numbers they perform: “dark” rockers (Nick Cave, PJ Harvey), an opera diva (Teresa Stratas), a jazz singer (Betty Carter), a torch singer backed w. classical musicians (Elvis Costello and the Brodsky Quartet), NYC legends (Lou Reed, David Johansen), and other surprise guests, including an utterly sublime final number that combines three elements into one scene of low-key magic. The show aired in 1994/5 (in various countries, with the documentary materials presented in different languages) and hasn’t been seen since. (The copy “hidden in plain sight” is unwatchable.)

1390.) Back to the “things you ain’t seein’ anyplace else” department on the show, this week I feature a discussion of, and scenes from, an anthology film that allowed a trio of arthouse directors to experiment with… the third dimension! 3x3D was created by the town of Guimarães, Portugal, when it was deemed a European “capital of culture.” They funded a short feature (one hour) in which three filmmakers could do anything they wanted, as long as it involved the 3-D process. In this episode, I focus on the first two segments (since the third is by J-L Godard, who always should get his own show). Portuguese filmmaker Edgar Pêra contributed a segment about the relationship between the movie viewer and the movie, explored from several different angles – he coins the term “cine-sapiens” for film buffs and comes up with some great images (although the piece as a whole does become abrasive). The master of historic trickery, Peter Greenaway, contributed a startlingly conceived piece in which we see the history of Guimarães, seen through hallways, arches, plazas, and other places where forgotten history lurks. Greenaway’s segment is the best in the film, as he densely layers the imagery. (Even in 2-D, the video looks 3-D.) Thus, you take a journey through a city’s past while seeing the possibilities for the “enlightened” use of computer effects – they don’t just have to be used to depict superhero fights, giant dystopic landscapes (with a very distant horizon), explosions, and random destruction!

1391.) The second of two episodes about the never-seen-in-the-U.S. feature 3x3D focuses on the short work of our fave, Uncle Jean (aka Jean-Luc Godard). I discuss, and show, his contribution to the feature, which is an anthology of three shorts made in 3-D with a budget from the Portuguese city of Guimaraes, which was declared a “European Capital of Culture” and wanted to commemorate that distinction with a film experiment (thus, the feature). Godard’s contribution is a continuation of his “essay films” (which he’d been making since the late Sixties, but which crystalized in the Nineties with his Histoire(s) du Cinema). We thus see film history, “samples” from the other arts (music, painting, literature), and samples of 3-D videography that Godard was doing as a rehearsal for his 3-D movie Adieu au langage. As a bonus, I throw in scenes from other Godard video shorts at the end of the episode.

1392.) A salute to a performer who always deserves a salute: Udo Kier. Kier has been in dozens of films in roles of different size, but few directors have ever figured out how to use him properly. I discuss this principle on this episode by showing scenes from the work of the late German filmmaker Christoph Schlingensief (who mostly made high-key, shrill, apocalyptic, self-referential fantasy films). First up is what should’ve been the dream film, 100 Years of Adolf Hitler (1989), which stars Udo as Hitler (with a cast of Fassbinder stalwarts as the others in the bunker); suffice it to say that the film doesn’t work, despite its noble deranged intentions. Next is The 120 Days of Bottrop (1997), an odd homage to, and abuse of, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, populated by many of his stars (and his producer, and his editor, Funhouse interview subject Juliane Lorenz)! The film finds a mentally disabled man playing RWF and the principals making a no-budget remake of Pasolini’s Salo while waiting for the star (Helmut Berger) to show up; it’s not easy viewing and the in-jokes will only work for major Fassbinder fans. The final film in the trio under consideration this week is the one that provides us with the best use of Udo – Egomania – Island Without Hope (1986), which features Udo in full flourish, relishing his dialogue, making faces, popping his eyes out, and giving what is definitely a perfectly Udo performance. The dialogue Schlingensief provides him with is prime choice – some stuff about him being “The Devil’s Aunt” and how he must kill Tilda Swinton’s baby. (Tilda is young and adorable; Udo is older and ready to kill a baby.)

1393.) Following the trail of cult movies around the world, this time we visit Uganda for the work of a gent named “Nabwana IGG,” who makes ultra-low-budget action comedies in his small town. Crazy World (2014) is the feature under discussion, and it is a joy – a no-budget spoof of Hollywod’s mega-million, CGI-riddled action pics (and Hong Kong’s slick and beautifully choreographed martial arts and crime movies, and basically any First World cinema’s hero-oriented sagas). The feature itself is delightfully funny and intentionally ridiculous, but the grace note is an onscreen “commentary” by a VJ who offers encouragement to the stars, context on their identity, pointers on the plot (which is barely there), and (my favorite) enthusiasm that bursts into declarations like “Movie! Movie! Movie!” Nabwana IGG has forged a style all his own (and a studio – “Wakaliwood”) out of the slimmest of means and the result is a very amusing view of the excesses of Hollywood. Movie! Movie! Movie! Indeed…

1394.) The pendulum swings away from high art this week as I present the fifth (and latest!) film by the indefatigable cult moviemaker (who hates the phrase “cult”) Neil Breen. Twisted Pair is a startlingly structured film that alternates slllllow moving drama, bizarre sci-fi, and preachy “message” moments in a classically “Breenian” stew. As always, Breen stars and wrote/directed/produced/edited/scored (with library music)/catered (with food he brought to set) the whole production and we’re very happy to note that, even in a film awash with CGI effects, he has remained as clueless about pacing, characterization, and plot logic as he was in the four films he made before this. Here he plays twin boys who grow up to be a pair of “AI” (Breen redefines the term as not a conceptual one, but simply to read “robot” or “android”). One twin becomes a good guy government agent, and the other deals in drugs, abuses his girlfriend and is just generally bad – so bad he wears a pasted-on insanely phony-looking beard. Breen is, if nothing else, consistent.

1395.) Labor Day is Jerry Lewis Day, even though he’s now departed. This time out I offer new “Jerry news” (post-mortem) and two items relating to his adoration by the French. The first is my own translation of bits of the epic poem that the great comic filmmaker (and real-life clown, who toured with circuses) Pierre Etaix wrote to accompany his sketches of Jerry in a limited edition book. Etaix discusses Jerry’s comic persona and his dedication to his craft, and compares him to the comedians of the Golden Age of Hollywood (both silent and talkies). The second half of the show explores the second of his French farces (which he at one point denied he’d ever appeared in), How Did You Get In? We Didn’t See You Leave (1984). The film is a forgettable trifle but does have some memorable moments, including physical shtick, an Asian impression (of course), and the one time Jerry was in a scene with women with bared breasts (!). It’s nowhere near as bad as Jerry thought it was. (Translation: Three on a Couch, it is not.)

1396.) Finally, in the “Too good for BBC-America” department, I’m able to pay tribute to the incredible talent of England’s finest monologist, Daniel Kitson. Kitson is a comedian and does do the occasional standup gig (where he’s quite fast with “crowd work”), but his supreme talent is for one-man shows in which he recounts stories about relationships, loneliness, memory (and its failure), and the importance of objects in our life. He’s a kinetic performer who is at once OCD in the ritualization of his theater pieces and also has a lightning-quick brain (as well as a stutter), so his live performances are the real deal – as he can’t help but be distracted from his monologue by audience activity. Therefore, seeing him on video is not as exciting as seeing him live, but the Funhouse is a TV show, so… there you go.

1397.) The second and last (for now) episode about the immensely talented British monologist-comedian Daniel Kitson focuses once more on his skill at outlining the daily existence of his characters, while delivering heart-tugging moments from “small lives.” There is humor galore, but at his best, Kitson sketches out a character through a profusion of detail (often communicated through “laundry lists” of activities or objects) and brings them vividly to life by making them seem like your neighbor, your friend, or yourself.

1398.) The Halloween season begins in the Funhouse with a two-part tribute to the man dubbed “Mister Monster” by Forry Ackerman – although he wasn’t really a monster/horror actor at all, outside of four or five films (out of the 150 he made, at least 50 as a star). This tribute to the inimitable Lon Chaney Sr., “the Man of a Thousand Faces,” covers the first part of his 1920s output, when he was a character actor becoming a star. The transition was made as a result of a series of long-suffering lead characters he played – Chaney’s pictures were “German humiliation films” several years before The Blue Angel brought that genre into existence. Lon went from playing “ethnic” parts and gangsters (what a mug on that guy!) to playing often-nasty or intimidating but always sympathetic characters. In this episode I discuss and show scenes from seven of his films, including the ones that made and confirmed him as a major box-office draw, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Also, two of his finest gangster pictures, The Penalty (1920) and The Blackbird, and one of his soapiest “ethnic” parts (and another amazing self-made makeup job), as a Chinese washerman in Shadows (1922). As Uncle Forry used to say, “Lon Chaney will never die!”

1399.) To further dip ourselves into the Halloween spirit, this week I present the second and final part of my tribute to Lon Chaney Sr., the “man of a thousand faces.” In this episode I focus strictly on the late 1920s, when Chaney made most of his memorably grim character studies, many directed by the sublimely twisted Mr. Tod Browning. Chaney’s portrait gallery of tormented souls includes a number of physically handicapped individuals, but also men doting on younger women who serve as surrogate daughters and also forbidden objects of desire. Lon was indeed a master-sufferer onscreen (and thus a superb silent-movie actor), and in the late Twenties he jumped from role to role, forging an amazing body of work that included bizarre crime dramas (The Unholy Three), character pieces (the Russian revolution tale Mockery), and some of Browning’s ultimate views of warped humanity and emotion (The Unknown, West of Zanzibar). Chaney worked with many different directors, but he truly was, according to Sarris’s categorization, the true “auteur” of the films he appeared in.

1400.) Nothing aired — screw-up in Access HQ!

1401.) Halloween gets underway in earnest with a series of episodes about the late, great monster-movie icon Bela Lugosi. In this first episode I explore Bela when he was riding high – as an immigrant from Hungary (via Germany) nabbing starring roles in melodramas and scene-stealing supporting parts in comedies and thrillers. His life story is filled with peaks and valleys, mostly because he was one of the single-worst decision makers in all of Golden Age Hollywood – due to agreeing to take a sub-standard rate as a movie star to play Dracula and a tendency to spend money as soon as he earned it, he declared bankruptcy within a year of the release of Dracula. In that same year (1932), though, he made three exceptionally creepy and unforgettable films – Murders in the Rue Morgue, White Zombie, and Island of Lost Souls, and essayed his first totally nuts modern mad scientist in Chandu, the Magician. I discuss Bela’s early career with clips of, and quotations from, the man, concluding near the end of the first “monster cycle” in the mid-Thirties.

1402.) As we move steadily toward Halloween, there isn’t enough holiday-related programming on the tube. My humble effort in this direction is this week’s a show, part two of a series of episodes about the up and (very) down career of Bela Lugosi. In this episode, I move from the mid-Thirties, when he was already firmly established as a star at both the major studios and their “poverty row” counterparts, to the early Forties, when Monogram was his true “home” for a time. The juxtaposition is dizzying – around the time of the beginning of WWII, Bela was playing supporting roles in major-studio productions like Son of Frankenstein (in which he created his second best-loved character, Ygor) and Ninotchka, and he was also starring in ultra-low-budgeted thrillers for Monogram. The latter are a source of fascination, due to the absolute weirdness of their scripts, and the fact that the first entry in this “cycle” of pictures was directed by Joseph H. Lewis, who was able to invigorate any genre film he worked on. Hang on, this will get even weirder in the episodes to come!

1403.) Halloween is a sacred holiday in the Funhouse and thus… part three of a four-part series about the up (and very) down career Bela Lugosi. This time out, we are deep in the Monogram years, when Bela still got parts in major-studio films, but it was usually as a red herring (most often a servant) or as a menacing supporting character. The bulk of his work in the early Forties was for “poverty row” productions that, surprisingly given their terrible production values, more memorable than the big-studio “B” features. This episode features scenes from the last few major-studio pictures Bela made – including the underrated Return of the Vampire and the strangest and definitely memorable Monogram Pictures, including the two “Ape Man” movies (which are, true to form, completely unrelated) and the stunningly strange Voodoo Man. Bela’s stunningly bad sequence of career decisions did result in some “incredibly strange” pictures that among the craziest “monster” pics in Hollywood history.

1404.) The fourth and final part of my Bela Lugosi tribute presents the comedic side of Bela (intentional and unintentional), as seen in the final features he played in. Even before Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, Bela was playing red herrings in whodunits and straight man to a bunch of comic acts – ever hear of Carney and Brown? No? Well, that’s okay…. In this show, I talk about and excerpt scenes from some of these films – including the infamous Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla, discussed before on the Funhouse when I saluted le cinema de Duke Mitchell and interviewed Sammy Petrillo. Included among the comedies is the only color film Bela made, a weird mix of creepy sequences and tongue-in-cheek nonsense with Bela and George Zucco (Scared to Death) and his very final Hollywood role, in which he had no lines. (He played a mute.) And then, of course, there was the trio of films with Ed Wood, the last one of which (Plan 9), Bela never knew he was a part of. (The footage he appears in was shot for a horror-movie project that never got off the ground.)