Two new books and a home-video release revive interest in a sublimely talented, and artfully warped, writer

(First published on time.com and used with the written permission of the author and publication of first instance.)

By Ed Grant

In the decade and a half that Terry Southern enjoyed fame as one of America’s pre-eminent satirists, he tackled every “grand theme” he could get his hands on: greed (The Magic Christian), politics and war (Dr. Strangelove), drugs and youth rebellion (Easy Rider), death (the script for The Loved One), alienation and the media (the script for End of the Road), and, with particular relish, sex (the novels Candy and Blue Movie).

What followed this period of critical and popular acclaim, however, was a quarter century in which Southern published a scant few articles and short stories, and one eloquent, compact novel that sank without a trace. During his “boom period” his screen credits included milestones like Strangelove and Easy Rider, contributions to campy time capsules (Barbarella), and uncredited work on high-profile projects (The Collector, Casino Royale). From 1971 until his death in 1995, only one movie – a dreadful Whoopi Goldberg vehicle called The Telephone (1988) — had Southern’s name attached to it. He was rumored to have “lost it,” alcohol and drugs having blunted his satiric edge. When mentioned at all, his name was preceded by the amiable but career-killing sobriquet “swinging’ sixties icon.” Though his ardent admirers continued to stress the ways in which his best work continued to inspire later generations of humorists and screenwriters, the question remained: What the hell was Terry Southern doing all those years?

Two new books do much to answer that question. The first, A Grand Guy: The Art and Life of Terry Southern by Lee Hill, charts Southern’s personal and professional highs and lows — and the star-studded array of folks with whom he shared them. The second, Now Dig This: the Unspeakable Writings of Terry Southern, is an anthology of previously uncollected writings and interviews that appeared in a range of publications, from the “quality-lit” (Southern’s phrase) mag The Paris Review to Puritan (the adult publication that was so explicit it was sold shrink-wrapped). Both books fill a significant void, offering evidence that Southern remained a potent, wildly creative scribe during his last 25 years on this planet. His skill in career-planning never matched his consummate wit and imagination (in fact he was a dismal dealmaker), but at least now his “invisible” years have yielded a number of characteristically strange and amusing stories, articles, and anecdotes.

A Grand Guy makes it clear that Southern’s finest creation was himself. The small-town Texan essentially reinvented himself after serving in WWII (he took part in the Battle of the Bulge), and taking advantage of the G.I. Bill to study at the Sorbonne. He eliminated his twang in favor of a precise, nearly British cadence, his Lone Star patois giving way to a flash, mockingly hip mixture of jazz lingo, eccentric abbreviations of names (as in “Sam” Beckett and “tip-top Tenn” Williams), the errant French phrase, and the occasional dip backward into down-home aphorisms. The following example of his odd parlance, found in Now Dig This, finds him lecturing about the way that the critical establishment has long ignored Poe’s novel The Narrative of A. Gordon Pym:

“…the systematic exclusion of this longest and very ambitious work of the most celebrated author in the history of the country smacks a little too strongly of the old gestalt – if you follow my drift. [They prefer] instead that the image of the ‘divine Edgar’ remain essentially that laid down by the late great Chuck Baudelaire, and the rest of the ‘frog elite’ (specifically Rimbaud, Mallarmé, and Valéry … with the incredible Verlaine abstaining – though not, scholars please note, through gayness alone).”

From Paris to Greenwich Village to mod London, Southern befriended some of the greatest writers, artists, and musicians of the day, spending hours sharing their pet indulgences. His status as a cooler-than-cool pop-culture icon was solidified by his appearance (shades and all) in the pantheon of heroes that populate the cover of the Sgt. Pepper album. Hill emphasizes that Southern created the “grand guy” persona to deal with an innate shyness; Southern’s collaborator Nelson Lyon is quoted as saying that as Southern grew older, he became a victim of his alter ego, “trapped in the cliches and hip jargon” that defined him in the eyes of friends and colleagues.

In the 1970s, Southern became “unfashionable” in the movie industry, due to several factors (changing regimes, the death of the “small” Hollywood film with the advent of Spielberg and Lucas, a reputation as one who “indulged” quite a bit). His position as a “name” journalist-in-residence on Rolling Stones tours had the same sad, resigned air as Ken Kesey’s travels with the Grateful Dead. Given the nature of his later professional endeavors (including the script of an unfunny 1980 hardcore porn comedy, Randy the Electric Lady), the sweetest surprise waiting for Southern fans in A Grand Guy is the revelation that he remained a productive and prolific writer during his “invisible” years. Though project after project went into turnaround, and ideas were hatched that seemed doomed from the start, Southern did produce completed screenplays for all of them. Some of the most valuable passages in Hill’s book offer tantalizing glimpses at these heretofore unseen scripts, including a project instigated by Peter Sellers about a meek, mild-mannered Pentagon auditor who stumbles onto the labyrinthine workings of the international arms trade.

The dilemma central to Southern’s life, post 1969, can be summed up in one question: why did he continue to labor on screenplays after it had become painfully evident that the mainstream movie industry (as well as the independent sphere, which he had helped to jumpstart with Easy Rider) had no interest in his work? Throughout these lean years, Southern could have easily veered back into what he called the “quality lit game,” given his well-respected status in the literary community. The most cogent explanation for Southern’s peculiar decision to stick with the film world can be found in his 1962 essay “When Film Gets Good…” (included in Now Dig This): “It has become evident that it is wasteful, pointless, and in terms of art, inexcusable, to write a novel which could, or in fact should, have been a film.”

Issues of creativity and expression aside, there was another, more concrete reason why Southern stuck with the movie biz: he acknowledged in an interview (also included in Dig) that “it is highly rewarding in the financial sense…” Therefore, owing quite a bit to the IRS, he looked forward to scoring a “breakthrough” film project that would simultaneously solve his financial troubles and resuscitate his standing in the Hollywood community. The juiciest anecdotes in Hill’s biography detail the curious way in which he pursued this breakthrough: in true self-destructive, Wellesian style, he hooked up with a variety of collaborators who were immaculately talented, but were further along in their alcohol- and drug-dependency than he was (Hill sketches Southern as a functional “user” whose biggest weaknesses were drink and Dexamyl — used to complete manuscripts on short deadlines): William Burroughs and a far-gone Dennis Hopper on an adaptation of Burroughs’ Junky; Larry Flynt and Hopper on a biopic of Jim Morrison; singer-songwriter Harry Nilsson, another “grand” soul, on the aforementioned Telephone.

The only thing missing from Hill’s excellent biography is the voice of the Master himself. Although the book’s subtitle emphasizes Southern’s life and art (and it is obvious that, after a certain point, his behavior in public became his “art”) sadly there are few quotes from Southern’s published work. Therefore, the uninitiated are urged to supplement Grand with a look at Southern’s finer writing, preferably Red-Dirt Marijuana and Other Tastes. Those who are content to know Southern’s work through viewings of Strangelove and Easy Rider will still be in for a treat, though, as they encounter “a certain yrs tly” (as Southern often referred to himself) and the “ultrafab” folks with whom he shared his life and times.

Offering an industrial-strength dose of Southern’s own special brand of high weirdness, Now Dig This contains some of the most profound, and downright silliest, things the man ever came up with. It is, in short, the “next book” Southern fans have been waiting for all these years.

Clearly a labor of love, the book is carefully structured, with Southern’s serious thoughts on literature, cinema, and drugs bracketing his work as a short-story craftsman, a critic, a New Journalist, and a writer of blissfully puerile “letters.” The pieces were selected and edited by Nile Southern, writer and son of the Grand Guy, and Josh Alan Friedman, musician, author of the terrific Tales of Times Square and a series of venomously funny cartoons, and the son of brilliant novelist Bruce Jay Friedman.

Besides two wonderfully candid interviews with Southern – in which he notes, among other things, that the film director is, for the most part, “an interfering parasite,” and “much of your time [as a screenwriter] will be spent in a creative wasteland” — the single most revealing piece in Dig is “King Weirdo,” his ode to his first literary hero, Edgar Allen Poe. Southern’s singular fascination for Poe’s duplicitous frame device in A. Gordon Pym — which insists that the story you’re reading is an account of actual events submitted to Poe — is reflected in several of his own short stories, including the marvellously titled “Heavy Put-Away, or a Hustle Not Wholly Devoid of a Certain Grossness, Granted,” found in this collection. An account of a mean prank worthy of Flannery O’Connor at her darkest, Heavy is one of Southern’s most pointed comments about human nature, and a perfect example of his crisp, succinct approach to writing (one can think of several crime novelists – e.g. think Donald Westlake – who would have spun Heavy into a full-length “scam” novel).

The most extreme and hysterical inclusions in Dig are short “letters” Southern concocted for the National Lampoon and the private amusement of his friends. Affecting an offhanded style, Southern gleefully raises the bar for bad-taste humor in these pieces, delivering bizarre gross-outs and politically incorrect (understatement) proclamations while tweaking various bastions of civilized behavior. Although the letters read like spontaneous creations, lacking the craft and precision of Southern’s best work, their surprisingly crude contents do satisfy his cardinal rule for successful writing: namely, that it possesses the “capacity to astonish.” The closest equivalents to a piece like “Hard-Corpse Pornography” (in which Southern outlines a necrophilic act practiced by soldiers in Vietnam) are other willfully perverse works by brilliant entertainers, like the later, cruder songs of one F. Zappa, or the dazzlingly vulgar Derek and Clive trilogy of albums by Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. Like those gents, Southern seems delighted to let his libidinous imagination take flight, but also delivers some devastatingly surreal satiric images — witness an account in one of the two Vietnam-related letters of fetishists (we will allow the enterprising reader to discover the true nature of the fetish) sporting jewelry composed of a certain part of the human rear-end. An ugly image to be sure, but one that deftly and savagely parodies the old Nam-era “jungle warrior” tradition of making a necklace out of the ears of one’s slain enemies.

Naturally enough, the spirit of the ’60s, “a magical era, an era of change and astonishments” pervades the book. Southern’s status as one of the forefathers of “New Journalism” is reinforced here with “Grooving in Chi” a first-person account of the “police riot” that occurred at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. Dig ends on a somewhat somber note, though, as ’60s survivor Terry recalls good times he shared with old friends (including Frank O’Hara and Abbie Hoffman) in a series of eulogies and tribute articles. These pieces make one lament the fact that Southern never got around to writing his proposed memoirs. Taken together, Grand Guy and Now Dig This do an admirable job of filling that gap – as well as increasing the average reader’s awareness of Southern’s strange and marvelous legacy.

The two new volumes offer a good introduction to Southern, as does www.terrysouthern.com the official Terry Southern homepage maintained by Nile S., which offers rare writings and assorted Terry-iana, as well as info on the as-yet-unreleased Southern tribute CD (recorded by Southern and a sterling cast, including Jonathan Winters and Southern disciple “Mr. Mike” O’Donoghue, shortly before Southern died). Further exploration of his small but influential body of work in print and on film is necessary if only to discover his dazzling inventory of effects. Certain works are dispensable (Telephone, Randy, the wonderfully funny but “high concept” novel Blue Movie), others are sadly unavailable (the elegiac, touching novel Texas Summer, the low-key experimental End of the Road, and the grimly funny The Loved One), while the seminal works are waiting to be experienced (or re-discovered) at local stores or through Internet vendors.

Southern’s first novel, Flash and Filigree (1958), was written under the influence of Henry Green, a dialogue-driven, slightly surreal British novelist of the same period. The book is constructed around three masterful set pieces: a curious encounter between a creepy doctor and his long-winded patient; the taping of a TV game show called “What’s My Disease?”; and what is without a doubt the ultimate ’50s seduction-in-a-drive-in scene. Southern’s dialogue is priceless, as the girl implores her fevered date, “…please don’t, really don’t please Ralph I can’t darling I love you please, oh Ralph, please, I can’t Ralph you don’t know please I’d rather die please God oh please God Ralph you’re hurting me oh no….” Shortly thereafter: “‘Oh Ralph,’ she breathed, worshipfully, ‘Ralph.’”

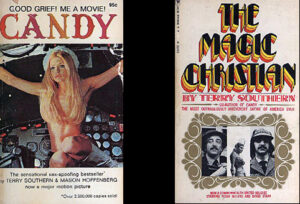

Written with poet Mason Hoffenberg, Southern’s best-remembered comic novel, Candy (1964) had a curious history: first published in 1958 under the pseudonym “Maxwell Kenton” by the Paris-based Olympia Press (a firm that printed trite erotica and debuted groundbreaking works like Lolita and Naked Lunch), the book fell into a strange copyright limbo on these shores. In interviews, Southern quoted the book’s sales at 7 million — it was a “New York Times” bestseller in its official U.S. edition, but thousands of copies were sold through bootleg printings of the book by no-name publishing houses, marketed as straight porn. Part in-joke, part social satire and part quickie porno novel, Candy is pure Southern. The protagonist, Candy Christian, is one of his finest creations: an update of Voltaire’s Candide, this middle-American college girl offers “charity” to every man she meets. Though written in the third person, the leering narration synchs up with the mock-erotic dialogue spoken by the characters: Candy’s womanhood is described with phrases like “honey-pot,” “jelly box,” and “sweetening damp”; her breasts are “pert and inquisitive,” and she beseeches a homeless hunchback, to whom she is being charitable, “Hurt me as they have hurt you … Give me your hump!”

The Magic Christian (1959) remains the most jarring and original in Southern’s slim bibliography. Entirely episodic, the book follows millionaire Guy Grand (stated goal: “making it hot for them”) as he uses his untold wealth to pay for elaborate scams and pranks, some of which prove that everyone has their price (money is dumped into a heated vat filled with blood, urine, and manure — to see how many folks will dive right in), while others are carried off simply to disrupt the status quo (a shrieking pygmy is hired to run a large corporation; a man smashes crackers with a giant sledgehammer on a crowded Manhattan street corner). The book clearly tapped into the zeitgeist of the time: the pranks and scams pulled off by Grand prefigure the performance-art “happenings” of later years, the carefree antics of Ken Kesey’s “Merry Pranksters,” and the media-grabbing events staged by Yippies Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin.

While Now Dig This is an entertaining, well-assembled collection of Southern’s writing, the “greatest hits” book he himself put together, Red-Dirt Marijuana (1967) shows the true depth of his talent, as the reader sees him adopting different styles and narrative voices, and nailing every one. The contents include Faulkner-like tales of a Texan adolescent (later reworked into Texas Summer) , an inner-city delinquent saga, a blissed-out, Kerouac-like account of a road trip, a journey into the mind of a tormented worker in the Paris metro, and an artfully drawn portrait of a wannabe hipster who hangs around black musicians (titled “You’re Too Hip, Baby,” its milieu may be dated, but its message is timeless). The most significant entry is his pioneering work of new Journalism, “Twirling at Old Miss,” in which ever-libidinous Ter visits a baton-twirling academy in Mississippi (where, curiously, the girls all seem to talk like Candy Christian) mere days after Faulkner’s funeral. His novelist’s eye colors his perceptions: “Next to the benches, and about three feet apart, are two public drinking fountains, and I notice that the one boldly marked ‘For Colored’ is sitting squarely in the shadow cast by the justice symbol on the courthouse façade – to be entered later, of course, in my writer’s notebook, under ‘Imagery, sociochiaroscurian, hack.’”

As for Southern cinema, one is surprised, given the fact that his “grand guy” persona was flamboyant and larger than life, that he never became a performer (like his comrades Burroughs and Mailer); his shy demeanor was doubtless the deciding factor. He can be seen in only four films: The Man Who Fell to Earth (as a journalist, in the restored version), the documentaries The Queen (where he judges a drag contest) and Burroughs, and the infamous Rolling Stones film-portrait Cocksucker Blues. The last–mentioned has never been officially available (the Stones hate it — but tend to excerpt it in their authorized video compilations), but it offers the longest glimpse of Southern onscreen. Shaggy and stoned, he dallies with what appears to be a powder as he declares “Cocaine’s so expensive that I don’t think it’s possible to develop a habit.” The camera swerves away at two intervals during his sequence — filmmaker Robert Frank tended to do this when his subjects were “indulging.”

As a screenwriter, Southern’s best-known work is undoubtedly Strangelove. Kubrick retained his services to turn the movie’s source-material, a rather starkly serious novel, into the “nightmare comedy” that set the standard for black humor in the ’60s. Southern’s warped sensibility is stamped throughout the film — especially in sequences like the one where Col. “Bat” Guano (“if that is indeed your name”) suspects Group Captain Mandrake of committing “preversions” in a phone booth. The other title invariably connected with Southern’s name, Easy Rider, demonstrates his mastery at delineating characters through dialogue — as in the memorable campfire scene where “straight” lawyer George Hanson (Jack Nicholson), conveys his admiration for Capt America and Billy but predicts that their liberated lifestyle is doomed.

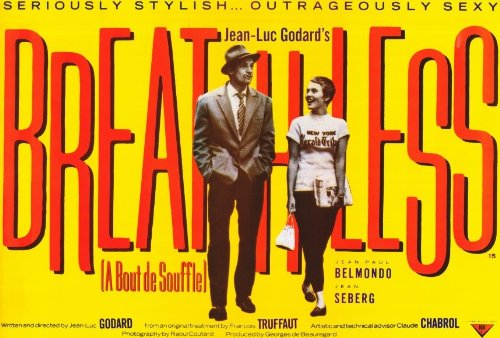

Though other Southern-scripted movies are available on video (most prominently Barbarella), fans of his work are advised to first check out the film version of Candy which recently made its home-video and DVD debut from www.anchorbayentertainment.com. On a par with Skidoo (1968) and Myra Breckenridge (1970) (both sadly unavailable) in the must-be-seen-to-be-believed category, Candy is a 100% product of the 1960s — lavishly budgeted, star-studded, exceptionally drug-inflected sex comedy.

A unique roster of stars—including James Coburn, Walter Matthau, and Charles Aznavour) — enjoy the “charity” offered by Southern and Hoffenberg’s nymphette, while scripter Buck Henry (dare this hardcore Southern fan say it) actually improves upon the novel in two bizarrely funny sequences: Candy’s worshipful encounter with drunk Welsh poet McPhisto (Richard Burton), leading to a more-than-peculiar basement menage a quatre involving her Mexican gardener (a Pepper-era Ringo Starr doing an incredibly awful accent); and her “lesson” with a guru (Marlon Brando) whose accent keeps changing from East Indian to New Yawk in mid-sentence. Henry and director Christian Marquand’s work on the rest of the movie isn’t nearly as successful, or true to Southern’s style (the gaudy trailer included on the DVD edition of the movie has the ironic tag line “Is Candy faithful? Only to the book”). Though the middle section is downright dull — that’s what fast-forward buttons and chapter stops were designed for — the finale is the sort of thing that could’ve only been dreamt up in the 1960s: the storyline has been neatly tied up, but the movie carries on, as our heroine strolls through a field, encountering every major (male) character she met previously in the film one by one – while Dave Grusin’s mesmerizing psychedelic score digs deeply into the brains of all who hear it.

Candy’s psychedelic glory aside, The Magic Christian is, for this reviewer, the most easily rewatchable Southern adaptation. Boasting the only onscreen union of members of the Goons, the Beatles, and the Pythons, the film stands as a kind of watershed in British movie comedy. Like the novel, it is an episodic affair, with some scenes working and others missing the mark (Southern himself disliked an amusing auction sequence written by and featuring a young John Cleese). Unlike the aforementioned psychedelic comedies, the cameos here produce intentional laughter. Laurence Harvey, Christopher Lee, Yul Brynner, and Raquel Welch (as “the Priestess of the Whip”) all seem to having a hell of a good time — generally a dangerous sign for a comedy (Yellowbeard, anyone?); here, however, the audience has one too.

Southern’s ideas live on – in print, in the movies he wrote, and, strangest of all, in the culture at large. As time moves on, it becomes clearer and clearer that he understood all too well the directions in which American society was headed. In Easy Rider, he anticipated the violent events (Altamont, Kent State) that blunted the idealism of the “love generation”; Dr. Strangelove was repeatedly cited by columnists writing about the Nixon administration (Henry Kissinger in particular was often compared to the good doctor); Guy Grand was definitely a forerunner of today’s eccentric millionaires — H. Ross Perot, Ted Turner, and that guy who paid millions to accompany the Russians into outer space; Candy Christian can be seen on daytime talk shows in the form of those young women who talk about the bloodthirsty serial killer they intend on marrying — “charitable” lasses indeed. From “The Jerry Springer Show” to the Supreme Court “selection” of the current President, one doubts that Southern would be a bit surprised at a single contemporary occurrence. Perhaps sociologists should pay more attention to those silly “satirists,” after all….

c. 2001, 2013 Ed Grant