1509.) Presenting scenes from another “film you ain’t seein’ anyplace else,” this week I highlight sequences from the French romantic comedy Adorable Liar (1962), directed by Michel Deville. The film is charming but slight, but it is worth highlighting because of its cast. Its two stars, Marina Vlady and Macha Meril, plays sisters from the country who are flirting with the men they meet in Paris. (Marina’s character is a liar who is eventually hoisted with her own petard.) The interesting thing with that pairing is that both women later worked for Funhouse favorite Jean-Luc Godard (separately but memorably). Other favorite performers appear in the film in small roles, including the great Michael Lonsdale and Pierre Clementi (whom we will be saluting in future episodes).

1510.) Vintage: A recent deep-dive into the work of filmmaker Ermanno Olmi led me to one of his finest “late” films, The Legend of the Holy Drinker (1988). This week on the show I’ll be discussing the film (which is available on DVD, one of only five of Olmi’s films to be released on disc in the U.S.). It’s an unusual “fairy tale”-like allegory that explores the nature of luck, faith, and indebtedness. Based on a novel by the Austrian Jewish writer Joseph Roth (who became a Catholic convert in Paris as he also became an alcoholic), it’s a beautifully rendered story of a homeless man (the late, great Rutger Hauer) in Paris who is lent money by a helpful stranger. He is instructed that, when he is solvent, he can leave the amount of the loan at a statue of a St. Therese in a small church. Thus follows a pre-“Groundhog’s Day” motif, wherein the man cannot get to the church at the right time to leave the loan at the statue; as the film goes on, he also encounters a series of benefactors in the first half and malefactors (read: crooks) in the second half. Olmi is a subject of some fascination, due to his having taken the tenets of Italian neorealism to “the next step” – using real locations, non-professional actors (in this film, the supporting cast), and documentary filmmaking techniques in the service of different types of fiction. Holy Drinker is a low-key character study that is also a beautiful silent film at times (with dialogue disappearing for entire atmospheric scenes), which contains one of Hauer’s best performances and a pointed message about the difficulty of ever paying back the people to whom you owe the most.

1511.) Interview with Balthazar Clementi, about his father, actor-filmmaker Pierre Clementi. This episodes focuses on Pierre C’s work as a filmmaker, which has been restored and championed by Balthazar, through screenings in various cities and a release of a complete box set (with English subs) in France. We talk about Pierre’s method of shooting and his unique editing (in which there was no negative, only the original copy on which he had overlaid numerous images). Our discussion moves outward from the original crop of films that Pierre shot to his only feature as a director (In the Shadow of the Blue Rascal, 1985) and the fact that his films comprise a chronicle of his personal life, his professional work onstage and in films, and his encountering other creative people (including filmmakers, musicians like Nico, and the Warhol coterie of superstars).

1512.) In the “you ain’t seein’ this anyplace else” department, I move back to the early Seventies once more for another post-Easy Rider film that a major studio made, trying to figure out what “the kids want.” The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart (1970) is a patchwork creation that follows a rich kid from L.A. who attends Columbia University and has various life-changing experiences. The most notable thing about the film (besides great location footage) is that the supporting performers, especially Holly Near as an open-minded coed and Michael Greer as a druggie hipster, are better than the lead, Don Johnson (in his debut film role). The film’s soundtrack is also of note, because some “heavy” pieces of rock are mixed in with original pieces performed by the Mike Curb Congregation, including the film’s one hit song, “Sweet Gingerbread Man.” The song is totally off-key with the tone of the movie, but that makes Stanley Sweetheart an even stranger early Seventies artifact.

1513.) For the Yuletide season it’s low trash for everyone! After I show a few un-p.c. clips from a Steve Allen seasonal special, we reach the “feature” of the evening, a micro-budgeted horror-comedy made with lots of consumer-grade CGI and some barely functional acting. It comes courtesy of Ashley Hays Wright, the no-budget filmmaker I saluted on Easter of this year – her cast consists nearly entirely of her family, with her daughters and husband taking on dozens of roles in her Xtian-pure and quite bizarre video features. Only on the Funhouse, kiddies….

1514.) For the New Year, I provide stuff from some old years. Clips from a trove of Steve Allen bootleg discs I bought off the Net, which were remarkably inconsistent in quality. I show only the best, though, focusing in on two shows: a 1976 PBS special that Steve hosted called “The Good Old Days of Radio,” devoted to the then-still-living stars of the shows that fit under the banner of what is now called “Old-Time Radio. And then the premiere of his Sunday prime time show (of which, a dreadful copy exists on the web). It was a star-studded episode featuring guests Kim Novak, the Will Mastin Trio (featuring you-know-who), and Vincent Price. I can think of no better way to ring in the New Year than with Steverino in the past.

1515.) Vintage: I am always happy to offer the “American TV debut” of scenes from “missing” films from our favorite filmmakers. Tonight’s a suitably deadpan, bizarre comedy from Takeshi Kitano (aka “Beat” Takeshi) called Takeshis’ (2005; don’t ask why the apostrophe is there – only Beat knows!). The film is part of his very strange “episodic” period, in which he made films that “build” narratives through details found in individual scenes that sometimes function as comedy sketches or tongue-in-cheek melodrama. In this film, there are two Takeshis – the famous filmmaker who is known for playing yakuzas, and an aspiring actor who works in a convenience store. We follow the latter as he goes to auditions, meets people who think he’s the famous Takeshi, and does other (doomed) jobs in his spare time. The film works as a great surreal comedy, with a “wormhole” universe in which our beleaguered hero keeps encountering the same people in different contexts, but it also does contain a lot of shooting action as Kitano includes cartoonlike violence in even his funniest films. (Know your audience!)

1516.) A significant discovery in the “You Ain’t Seein’ This Anyplace Else” department, so significant I’ll be doing two episodes about it. The 1979 film TRAFFIC JAM, directed by Luigi Comencini, looks on surface level to be an all-star “high-concept” comedy: a bunch of cars involved in a traffic jam boil over with crazy situations. However, the film is filled with comedy *and* drama, and the casting of great stars isn’t just a stunt, it actually contributes to the dramatic (and comedic) value of the piece. The situations do indeed move from the broadly farcical (an uptight young man trying to quit smoking will be made late for a very important date with his inamorata by the traffic jam) to the dramatic (an unwitting man doesn’t realize his best friend is screwing his wife), but there are also plots that qualify as political (an upper class lawyer who claims to have high-placed Socialist friends complains about the commoners caught in the jam) and tragic (a young hippie girl is targeted for rape by three young men watching her throughout the proceedings). The cast includes leading actors from Italy, France, Spain, and Germany; they include Mastroianni, Depardieu, Sordi, Girardot, Tognazzi, Dewaere, and Miou-Miou, among others. It’s not what it would’ve been, had it been made in the U.S. It’s TRAFFIC JAM.

1517.) Part 2 of a discussion of, and scenes from, the never-released-in-the-U.S. all-star comedy-drama TRAFFIC JAM. In this final part of my showcasing of the film, you’ll see how the drama kicks in and, while the comedic elements are still around, the two screenwriters who collaborated with director Luigi Comencini (one wrote for Fellini and the other scripted the terrific IL SORPASSO, shown on the Funhouse decades ago) brought the main plots to a boil, especially one involving a hippie girl (Angela Molina) and her trucker suitor (Harry Baer). The film is surprisingly good and is about as far away as American “car comedies” as you can get. The cast list speaks for itself: among the stars featured are Mastroianni, Depardieu, Girardot, Tognazzi, Sordi, and Miou-Miou. As noted above, the film has never had a U.S. distribution deal and sadly prob never will.

1518.) Vintage: Following the trail of my favorite filmmakers takes us down some interesting alleys on the show. This week I review and show excerpts from a comedy by Takeshi Kitano (aka Beat Takeshi) that hasn’t been shown in America at all, Ryuzo and His Seven Henchmen (2015). The film is a yakuza farce about old gangsters who are bored with being treated “old farts” (the single most-used phrase in the movie), so they band together as a new criminal gang. The situation is somewhat familiar to American viewers, but Kitano’s take on the scenario is that the old-fart yakuzas face off with the new criminal generation: crooks in suits who do their thieving and conniving in corporate boardrooms. Beat has played a yakuza numerous times over the past few years, so here he cast himself in a supporting role as a cop who has a soft spot for the old gangsters (as one suspects the real Kitano does). I’m happy to share scenes from this film, which has never been seen on these shores.

1519.) Screw-up from Access HQ!

1520.) NEW: Part 2 of my tribute to the work of actor-filmmaker Pierre Clementi includes more of my interview with his son, Balthazar. In this show we finish talking about Pierre’s filmmaking, focusing on his most personal work, “Soleil” (1988), which he narrated and which features footage of his family and recreated scenes of the Italian drug bust that changed his life in the early 1970s. From there we discuss the memoir Pierre wrote about his year and a half in jail for a crime he didn’t commit; the book is now available in English translation for the first time (from the small press called Small Press). As bonuses, we talk about Etienne O’Leary, a sadly forgotten but very talented Canadian “underground” filmmaker whose work influenced (and starred) Pierre, and later on, the cult film I showed on the Funhouse many years ago, LES IDOLES (1968) and how it grew out of pioneering theater-cafe work in Paris that Pierre did with the director Marc’o and his costars and friends, Bulle Ogier and Jean-Pierre Kalfon.

1521.) Reaching back to the “Forgotten Filmmakers of the French New Wave” festival, this week I discuss and show clips from another film that has never been released in the U.S. on disc, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze’s L’eau a la bouche (1960). Doniol-Valcroze co-founded “Cahiers du Cinema” and wrote/directed some very intriguing films (including Le Bel Age, which I showed on the show some months back. Bouche is a film that involves family members returning to an old mansion for the reading of a will. Ordinarily this might signal a thriller of some kind, but here, the focus is on a case of mistaken identity (a boyfriend of some relative is taken for her long-lost brother; the lovers encourage this deception) and the new couplings of the four major characters (and the butler’s insistence that he must sleep with the maid, played by Funhouse guest Bernadette Lafont). The film is a good little drama made much better by an original score (and haunting theme song) by Serge Gainsbourg in his earlier, jazzy mode. Where else can you hear “Sweet Georgia Brown” turn into Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring”?

1522.) Vintage: Back in the “Too Good for BBC-America” department, this week I present a discussion of, and clips from, Inside No. 9. The show is a sharply scripted anthology series written by and starring former League of Gentlemen members Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith. Each episode tells a different tale, with the entries ranging from quiet character studies to all-out horror and suspense. The episode I focus on this week is “A Quiet Night In,” a pretty brilliant modern updating of Laurel and Hardy. Pemberton and Shearsmith play burglars intent on stealing a modern minimalist painting (it’s basically just a white canvas) from a rich man’s house. The rich man is arguing with his significant other, so they aren’t speaking, and thus we have a dialogue-less, BBC-budgeted, comedy outing that does indeed function like a 21st century updating of the old “two-reeler” comedy scenarios. Pemberton and Shearsmith are much lauded in the UK, but over here their creations have mostly been aimed at horror fans — although that element is only a part of their work, with Inside No. 9 proving they are in the top rank of today’s TV scripters.

1523.) I haven’t yet shown anything on the Funhouse from filmmaker Terrence Malick, who did the miraculous trick of taking two decades off from directing and then returned with a group of films that showed a unified vision and did indeed pick up where the “maverick” cinema of the Seventies left off. In this episode, I show scenes from the unseen-in-the-U.S. (aside from a handful of festival screenings) 2016 feature version of VOYAGE OF TIME (which was released by the IMAX people in a differently edited 45-minute version narrated by Brad Pitt). The feature boasts a narration by Cate Blanchett who speaks to an unseen “mother” (you decide – nature, the Earth, God?) as we see the formation of the universe and the evolution of the human race, counterpointed by communal rituals from various cultures. The result of four decades of thought and planning on the part of Malick (along with siphoning off budgets from other features to create certain sequences), TIME is a unique work, in that it shows one of the great American mavericks offering a meditation on, basically, everything. It will not go down as his last film (he has already made one terrific feature since), but TIME is a sort of “ultimate” film that, while showing the influence of other filmmakers (from avant-gardists and “undergrounders” to Kubrick and Godfrey Reggio), is wholly unique and original.

1524.) Four famous “French” directors died in September of 2022. Only one of them was French by birth; the remaining three were born elsewhere. Just Jaeckin was the true Frenchman; I’ve yet to do a Jaeckin episode on the show (although I enjoyed his softcore whimsy). William Klein, born in NYC, has been celebrated several times on the Funhouse. The biggest name, initials JLG, was born in Switzerland and retreated there in his later years; he remains a Funhouse staple. The fourth filmmaker to die in September was Alain Tanner, whom I’ve paid tribute to twice on the program (and have loved very much all of his early work and a few later items). He was born and died in Geneva and was indeed 100% Swiss. He was lumped in with the French because he made films in French and also had encountered the New Wave (and their mentor and hero, Langlois) in the Fifties. Here is a commemorative replay of one of the shows I did about Tanner….

Returning to the topic of films you ain’t seein’ on TV anytime soon, this week I discuss and show scenes from Messidor (1979). The film is Alain Tanner’s portrait of two young women who meet while hitchhiking and then wander across the Swiss countryside, having been classified as criminals. These days, the film strikes one as being the original version of Thelma and Louise, but Messidor is a lot less romantic and glamorous, and deals with the realities of life on the road – where does one sleep? Where do you go to the bathroom? Where do you find money, and more importantly, who can you trust? Tanner uses a “leisurely” style of filmmaking, in which long takes and long shots stand in for flashcuts and dramatic close-ups. The two leads (Clémentine Amouroux and Catherine Rétoré) are terrific, playing women of 18 and 19 who think of of their unplanned trip as a “game” of endurance.

1525.) The third and last part of my interview with Balthazar Clementi, son of actor-filmmaker Pierre Clementi, moves to the latter portion of his life, where Pierre succumbed to alcohol addiction, leading to his early death at 57. We discuss his legacy as an actor and spotlight Balthazar’s favorites of his father’s many performances on film (enabling me to show clips from films I haven’t yet featured on the Funhouse). We also talk about Balthazar’s mother, Margareth, who had an acting career that she eventually gave up in search of spiritual pursuits; she had featured parts in films by Pasolini, Fellini, and Werner Schroeter, among others. Our interview ends with Balthazar outlining his hopes for his father’s films (as a director), for which he is the rights holder and conservator.

1526.) Repeat of above episode, as it was shown improperly by the Access HQ folks.

1527.) Vintage: I start off a Deceased Tribute tribute to the legendary Seijun Suzuki with this episode, the first of two shows devoted to his work. In this episode, I discuss his “explosion” of the studio-assigned genre movies he made with innovative camerawork, editing, and truly bizarre action (the final clip in the show is my vote for “craziest Suzuki moment ever”). The focus is of course on his yakuza pictures, but I found that, in assembling the clips I present, you get a wide range of “moods”: from romantic drama to imaginatively brutal violence to broad, bizarre comedy and color-coded, kinky, widescreen erotica. Suzuki was a “B” director in the late Fifties and Sixties, but his work is far more interesting than many of the “A” filmmakers working at the time.

1528.) To celebrate the Paschal season, it’s time for another “inspirational” movie, which means a film that generally hides its Xtianity behind a mawkish plot until a certain dramatic point is reached, and a film that conveys way too much of its exposition in dialogue. This time out it’s the oddly named C ME DANCE (2009), a tale of a teen aspiring ballerina who is diagnosed with leukemia but then gets a special Gift From Above – she can make believe in JC by just touching them! At this point, the ultimate bad-movie-redeemer comes in (the Devil) and the proceedings become even more headscratching. The film does come equipped with: a girly visit to the mall, ballet sequences (which I cut – we’ve only got 28 minutes!), and yes, visits from the Horned One. It never became a hit at the box office, but C ME DANCE does have the advantage of seeming like it came from another planet, and that’s what I enjoy showing each Easter weekend on the show.

1529.) Following up on my episode about the New Wave film ADIEU PHILIPPINE from some months ago, this week I present a later film by the same director, MAINE OCEAN (1986). The filmmaker, Jacques Rozier (still alive as of this airing, at 96!), had many difficulties in getting films financed (and then finished), so as of his second feature he turned to making comedies. The odd thing about his comedies, though, was their length — always well over two hours long, his films were shot in a documentary style that gave the films the air of being entirely ad-libbed, but they weren’t. Rozier had definite ideas of where his plots had to go and he did script (here with a costar, Lydia Feld) a lot of the “loose” dialogue that seemed as if it was improvised. In recent months, two long comedies were up for Oscars (and one — the lesser of the two — swept the awards), but Rozier’s version of “long comedy” is different because of his reliance on documentary shooting techniques (handheld cameras, interpolated instances of other real-time action, cross-dissolves to indicate the passage of time) and the incredibly deadpan humor found in the films. In his fourth film, MAINE OCEAN (his first film to make money at the box office), he assembled a wonderful ensemble of character people who knew how to incarnate his bizarre characters and allowed them to take his odyssey while constantly making little speeches about their beliefs (with the two female leads being clear-headed and the male characters being a colorful assortment of dolts).

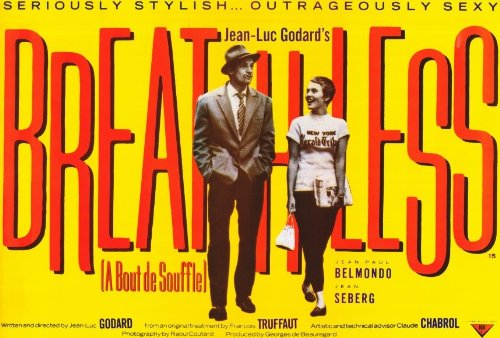

1530.) When Jean-Luc Godard, one of the single-most important filmmakers in the past 60-plus years, died in the Fall of 2022, I knew I would eventually have to start a series of episodes tackling his inarguably brilliant legacy. (For the time being, I re-edited older Godard episodes and showed them at the time.) Thus, this week I begin my Deceased Artiste tribute to Uncle Jean with a show that presents a “101,” dealing with 9 of his first 10 features. I’ve used some of these clips in preceding tributes to Godard (and Anna Karina), but seen together they give one small indication of just how influential and innovative JLG’s work has been over the years. (With new generations of filmmakers discovering his work every few years, thanks to film schools, repertory theaters, home-entertainment formats, and the Internet.) It’s startling to realize that how much he changed film language with the 10 features he made from 1960 to ’65 — and that this was only the beginning of his simply amazing career.

1531.) A change of pace on the show this week, as I move into the world of favorite films of Mr. Lux Interior, lead singer of the Cramps. Lux and his soulmate Ivy Rorshach were fanatic record collectors but they also collected movies on tape (yes, this was the ’80s), specializing in the sleazy and outré. Sometimes, though, Lux’s taste was a little closer to the mainstream, although still wonderfully psycho — as is the case with a film he recommended in one of the two books written about the Cramps, Love from a Stranger (aka “Night of Terror,” 1937). The film is both a thriller and a “woman’s picture” (in the way that the later Gaslight is a woman’s picture), scripted by Frances Marion (Dinner at Eight) and based on a story by Agatha Christie. The plot is incredibly straightforward: average woman wins the lottery and suddenly encounters a debonair suitor, played to perfection by Basil Rathbone. In quick order, she leaves her apartment, breaks up with her fiancee, and drops her best friend to marry and live in the country with Basil. Basil, however, starts acting a little crazy and our heroine starts hearing stories about a man who marries rich women and kills them for their fortunes…. The film goes from being a full-on melodrama to basically a filmed play, but the two leads are both terrific, with Ann Harding gradually realizing that she’s most likely going to be murdered, and Basil flying off the handle in wondrous ways. He might have been best-known as Sherlock Holmes and Wolf von Frankenstein, but his turn here is quite memorable.

1532.) The second part of my tribute to Uncle Jean (aka Jean-Luc Godard, master filmmaker) covers the second half of the “golden 15,” plus some. I discuss various books about JLG, talk about the audience at one NYC-area rep theater, and then the clips commence. The films excerpted date from 1966 to 1969, showing Godard doing his last classically “New Wave” film (MASCULIN FEMININ) and then moving on to a genre-movie deconstruction (MADE IN USA), an essay about urban renewal *and* the artist’s decisions concerning which narrative to tell (2 OR 3 THINGS I KNOW ABOUT HER), and then onto his “final” films for the Sixties, in which he confronted radical politics with bright colors and charismatic lead actors (LA CHINOISE) and then finally declared “End of Cinema” with a grim view of Western civilization in the form of a bourgeois couple traveling from the city to the country (WEEKEND). As a bonus I include scenes from films made after Uncle Jean’s declared the “End” (which of course never really happened — he just left conventional plots and characters behind for most of the following decade). I only chose one pop music-driven scene, as that is certainly another direction he went in in the latter half of the Sixties (but we only have 28 minutes on the air).

1533.) Going to the “low trash” end of the spectrum (and the early years of the Funhouse) for some entertainment, this week I present another film that was a fave of Lux Interior of the Cramps (so much so that he wrote a song using the film’s title), CONFESSIONS OF A PSYCHO CAT. The film is a truly odd concoction, as it is the umpteenth adaptation of the “Most Dangerous Game” scenario (wherein a human being is hunted instead of an animal), and it also was peppered with truly flat and awful softcore sex scenes by its distributor to pep it up. These scenes aren’t really needed, as the film itself is as crazy as they come: the hunter here is a rich woman (the sister of a “Great White Hunter”) who offers a deal (money if they can flee her) to a down-on-his-luck actor, a beatnik junkie, and a former wrestling champ (played by real-life broken-down fighter Jake LaMotta). The film boasts wonderful NYC locations and crisp black and white photography and is otherwise bugfuck crazy – the actress who plays the hunter (wearing an obvious wig) plays her character throughout at a pitch that is well over the top, while the other performers have to mostly just register surprise and terror. (Including the “Raging Bull,” who is most mockingly killed like a bull.) Plus, all that bad mismatched softcore footage.

1534.) In recent years I’ve circled around various figures in French cinema. In this show I’ll combine a few fascinations with a discussion of, and excerpts from, Michel Deville’s Benjamin, or the Diary of an Innocent Boy (1968). Deville, who recently joined the Deceased Artiste ranks (and has been explored on the Funhouse in the past), was a stylish director and a contemporary of the New Wave, who worked in a number of different genres. In Benjamin he reunited three of the stars of Belle du Jour – Catherine Deneuve and Funhouse faves Michel Piccoli and Pierre Clementi – and added in the great star Michele Morgan for a period sex farce. The plot follows a virginal young man (Clementi) as he is mentored by a lady’s man (Piccoli) and discovers the vagaries of courtly love and sex. Scripted by Nina Companeez (who wrote Adorable Liar, recently featured on the show), the film is a light and breezy farce that has some wonderful set pieces, most of which have to do with Benjamin’s naivete around the fairer sex. The film is delightful on several levels, one of which is seeing the cast of Bunuel’s masterwork playing against the “types” they played in Belle.

1535.) Jumping out of chronology in a ongoing series of Deceased Artiste episodes about Jean-Luc Godard, this week I present a discussion of, and scenes from, the 2022 film A Vendredi Robinson (Until Friday, Robinson). Filmmaker Mitra Farahani, who produced Godard’s final feature, crafted a delightful chronicle of the “correspondence” (conducted through email, photos, and video) between Iranian filmmaker and author Ebrahim Golestan and Godard. The film offers a fascinating look at two sharp minds (Golestan at age 92, Godard at 84; the film was shot in 2014-15) comparing notes about aging, society, and art. The film also delves into the personal lives of both gentlemen: while Golestan has a partner and people constantly communicating with him in his home in England, Godard is depicted as exceptionally solitary in Rolle, Switzerland. Robinson offers a good introduction to Golestan and a wistful final look at Old Master JLG in the period before illness finally slowed down his productivity. It’s exhilarating to see him still investigating old favorites (Dashiell Hammett novels, Johnny Guitar) and sad to see him returning again and again to a discussion of impending death (and its corollary for him, “self-death”).

1536.) Vintage, in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Seijun Suzuki’s birth!: Part two of my Deceased Artiste tribute to Seijun Suzuki picks up where I left off in the first show – with the film that got him fired from his studio, the vibrant, clever, stylish, and completely crazy yakuza drama Branded to Kill (1967). From that point we jump to his “comeback” in the late Seventies with a Funhouse favorite, A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness, a peculiar meditation on fame and how women are ground up in show business. Then it’s on to his arthouse period with the “Tasho trilogy,” three films set in a period where Western styles were taking over Japan (and Alain Resnais-like fugue states and fluid identities have taken over Suzuki’s characters). We end as his career did, with the outrageous and imaginative Pistol Opera (a variation on Branded to Kill from 2001) and the trippy musical Princess Raccoon (2005). I’m very proud to do this exploration of Suzuki’s career, because the work of his famous filmmaker fans is well known to most arthouse viewers, but his own films are known mostly to cultists.

1537.) Vintage: Certain cult TV shows slip through the cracks of the U.S. DVD/Blu-ray market – one such title is the mid-Seventies British musical drama “Rock Follies,” which I salute this week for the first of three episodes. Created before punk really hit and a few years before Dennis Potter let it rain “Pennies from Heaven,” the “Follies” was an odd creation – a “modern” rock drama in the mode of the old Busby Berkeley musicals, where young women rise in show business, with all the attendant egos, arguments, and incredibly catchy music. The last-mentioned in this case was supplied by Roxy Music’s Andy Mackay (with lyrics by the show’s scripter, Howard Schuman, who “borrowed” the story of the singing group from a real-life women’s combo). The cast is also wonderful, delivering both the coyness of the “young singer goes out there a nobody… and comes back a star!” performers and the sincerity of working-class ladies trying to move up in “the rock music” while also dealing with demanding partners.

1538.) Sometimes you spend years looking to see a specific film. In this case, the film is Chief Zabu, an off-studio comedy that was made as a vehicle for the late, great Allen Garfield and comic actor Zack Norman. The film was shot in ’86-’87 and yet was never assembled or released at the time. This would have gone unnoticed, but for the fact that Norman’s agent had taken out an ad in “Variety” that ran on a weekly basis from ’85-’88 promoting the film and his part in it. This ad drew attention to the project — before, during, and after its shooting — and then became a kind of “What *was* that?” joke in later years. Finally, in 2016, the film was assembled and released by co-director and star Norman (aka Howard Zuker, his real name); the assertion at that time was that the film features a Trump-like realtor who aspires to political office, which is only true in one scene (and one snippet of dialogue that Zuker pointed to as being inspired by Trump). In any case, it’s a light, breezy comedy about inept con men trying to get a financial foothold in a small (fictitious) Polynesian nation. The cast is made up of familiar faces and names, including Allan Arbus, Shirley Stoler, and Ed Lauter, but it is Garfield and Norman’s scenes as a comedy team which are surely the best parts of the picture.

1539.) Vintage: Part two of a three-part tribute to the cult British series “Rock Follies” finishes off the first season of shows, the last time the series had some form of sensible continuity. The catchiest musical numbers by Roxy Music vet Andy Mackay appeared in the latter half of the first season, and the lead characters reached a turning point where their girl singing group was turned into a “nostalgia act” by a Greek mogul. First, it’s the Thirties, then it’s the Forties, then the group is screwed totally, leaving way for the second series (titled “Rock Follies of ’77”). On this episode I’ll be discussing the series, which has never been available in the U.S. on DVD, Blu-ray, or VHS, and hasn’t been shown on PBS since the late Eighties. The songs and the lead performances make the show worth watching in any decade – it’s a relic but a fascinating one, with great tunes by Mackay.

1540.) Vintage: The third and last of my tributes to the cult British TV series “Rock Follies.” This time out I’m discussing and showing scenes from the second (final) season, called “Rock Follies of ’77.” The show truly jumped the shark in this season, but there are still things to be enjoyed. The plot chronicles the fragmentation of the show’s trio of women singers, but the songs (with catchy melodies by Roxy Music’s Andy Mackay) are memorable, as are the lead performances – although rock belter Julie Covington was fast becoming the show’s star and the other two “Little Ladies” were left in her wake (both in the plot and on the show). Although the first season was very popular on PBS, this season wound up not being played until the late 1980s because of “raunchy” plot elements, which would scarcely raise an eyebrow today. The element that will please current American viewers are the guest stars: Tim Curry steals one episode as a terrific would-be UK Springsteen or Lou Reed (read: a phony ex-gang member/performer who’s “a poet of the streets”), and Tim’s RHPS costar Little Nell and the soon-to-be-famous Bob Hoskins are memorable supporting players.

1541.) Vintage: The first of three episodes devoted to the great work of the brilliantly subversive filmmaker Robert Aldrich. These shows came out of watching (and being annoyed by) the overwrought miniseries “Feud,” which dragged Aldrich’s reputation through the mud and ignored his many accomplishments making independent films with and without studio backing. In this episode I focus entirely on the Fifties and the string of genre pictures he made that overturn the genres in question. The films included in the show range from his first adventure/noir film World for Ransom to his mid-Fifties slew of splendid genre movies, including two great Westerns (both with Burt Lancaster), a “woman’s picture” (with Joan Crawford), a why-Hollywood-is-evil melodrama, and two of the greatest subversive films ever, his anti-war war movie Attack! (1956) and one of the best (and arguably the “last”) noirs ever, Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

1542.) Back to the garden of unseen films for a Sam Fuller picture that was made while he was living in Paris in the Eighties. Thieves After Dark (“Thieves of the Night” in French; 1984) suffers a bit from having been dubbed in a rather lame fashion, so all the French performers’ voices are not their own (although the film was shot in English). The film itself is a fun, perverse and ultimately sad journey for a couple of young lovers who are unemployed and hate the agents at their local unemployment office. They decide to humiliate these mean individuals, and this results in the “lovers on the run” third act. The film benefits from some good supporting performances, including those by Sam himself (as a fence who can’t stop watching Isabelle Huppert on TV) and Claude Chabrol as a pervy unemployment agent who will go to any lengths to see a girl undress. The film is not quite peak Fuller, but it has some terrific moments.

1543.) An underrated U.S. indie filmmaker is saluted on this episode, as I discuss and present clips from the third film by Rob Tregenza, Inside/Outside (1997). Tregenza’s name has been mentioned in the same breath as Jean-Luc Godard, as “Uncle Jean” loved his first feature and thereby (uncredited) produced this film. Tregenza is an immaculately talented filmmaker, whose strong suit is creating a film out of long takes in which the camera moves lyrically around the settings, “telling the story” more than the dialogue (which is very minimal in Inside/Outside). Thus, in this episode I tried to be true to his approach by presenting a series of a few scenes from the film, nearly each one of which is comprised of a single take; this reaches its zenith in an absolutely brilliant eight-minute scene in which the inhabitants of a mental hospital watch a concert that falls apart. The plot is a simplistic one, about the burgeoning love affair between a young man and woman in the asylum. The performances (by two stars of Godard’s film For Ever Mozart) are very good, but it is the brilliant single-take approach (and exquisite camerawork — Tregenza has worked as d.p. for other filmmakers, including Alex Cox and an absolute master of long takes, Bela Tarr) that makes the film so memorable.

1544.) NEW/Vintage: Jane Birkin interview, part 1.

1545.) NEW/Vintage: To commemorate the passing of Jane Birkin, I’m showing a digitized and updated version of the second part of my interview with her from September 2003. My original description: The second and final part of our interview with Jane Birkin. Ms. Birkin shares further reminiscences of the mythically indulgent genius Serge Gainsbourg, and talks about working with Jean-Luc Godard in Keep Your Right Up and Rivette on Love on the Ground. Also: Ms. Birkin reflects on the ’60s psychedelic farce Wonderwall and Mr. Gainsbourg’s debut as a filmmaker, Je T’aime Moi Non Plus.

1546.) The first of a two-part dive into a rarely screened item called Movie Orgy, initially made by Joe Dante and Jon Davison when they were both students at the Philadelphia College of Art in 1966. The ORGY is a compilation that used to be shown as a “happening” wherein various 16mm projectors were used, with Dante and Davison would switch projectors to move from a group of B-movies sci-fi movies they owned on 16 to copies of old television episodes (mostly children’s entertainment), classic Hollywood films from the Golden Age, commercials, industrial films, and public service works. The result was a “film” of various lengths (running as long as seven hours at one point, but preserved by Dante digitally at around 4:45) that changed from showing to showing. Since the Funhouse runs along similar lines (minus the quick-take cut-ins), I wanted to explore this giant work by showing some of the most jarring material and offering commentary on what the Orgy seems to be all about – namely, ’60s/early ’70s young people reflecting back on their childhood in the ’50s and just how much importance TV (and old movies on TV) had in terms of building their world view. That may sound academic, but the contents of the Orgy make it just a full-blast nostalgia orgy that includes some rarely seen items (and even a few that are never, ever shown out of the context of this compilation).

1547.) The second part of a two-part discussion and clip-fest from Joe Dante and Jon Davison’s marathon clip compilation Movie Orgy. I wrote about it for the Media Funhouse blog (at http://mediafunhouse.blogspot.com/2023/04/notes-on-screening-of-movie-orgy-aka.html). For a capsule history, I’ll just repeat here what I wrote for part one: ORGY used to be shown as a “happening” wherein various 16mm projectors were used, with Dante and Davison switching projectors to move from a group of B-movies sci-fi movies they owned on 16 to copies of old television episodes (mostly children’s entertainment), classic Hollywood films from the Golden Age, commercials, industrial films, and public service works. The result was a “film” of various lengths (running as long as seven hours at one point, but preserved by Dante digitally at around 4:45) that changed from showing to showing. Since the Funhouse runs along similar lines (minus the quick-take cut-ins), I wanted to explore this giant work by showing some of the most jarring material and offering commentary on what the Orgy seems to be all about – namely, ’60s/early ’70s young people reflecting back on their childhood in the ’50s and just how much importance TV (and old movies on TV) had in terms of building their world view. That may sound academic, but the contents of the ORGY make it just a full-blast nostalgia orgy that includes some rarely seen items (and even a few that are never, ever shown out of the context of this compilation).

1548.) Sometime a film is so uniquely suited to the Funhouse that it needs a tribute episode based on its premise alone. Such is Helsinki Napoli All Night Long, Mika Kaurismaki’s 1987 nighttime comedy about cabbies, hookers, drunks, and gangsters, featuring a cast sprinkled with Kaurismaki’s filmmaker friends. The plot follows a Finnish cabbie (Kari Väänänen, star of some of the best films made by Mika’s brother Aki) as he roams West Berlin after enountering two gangsters and a briefcase full of money; he feels this will make his Italian wife (Roberta Manfredi), who also happens to be his dispatcher, happy, but he figured wrong. I’ve paid tribute to Aki K. countless times but have only talked about a movie by his brother Mika once before on the show. Helsinki is a natural for the Funhouse as it is set in the wee small hours, is a dark [ouch] comedy, and features as its lead gangsters none other than Sam Fuller and Eddie Constantine. (Kaursimaki friends W. Wenders and J. Jarmusch also have supporting roles.) It also now stands as a sort of late Eighties time capsule, given its synthesizer score and its pre-Wall-coming-down look at a polyglot European city where everyone conveniently speaks in English – except yet another guest star, Nino Manfredi, who speaks in Italian (without subtitling, but everything he’s saying is pretty comprehensible).

1549.) Having paid tribute to Jerry Lewis since 1994 (the Funhouse came on the air in Sept of 1993), I have pretty much nothing new to say about the guy. However, when certain rarities featuring him come my way, I have to feature him again on the show (and most certainly it’s best to do this on Labor Day!). In this case, I actually sat and subtitled (with an old editing program that doesn’t allow for two lines of subtitles, which made the task even more arduous) the footage, since it not only involves Jer and his giant ego, but also a major French actress and an underrated New Wave filmmaker. The last-mentioned is Jacques Rozier (the subject of two episodes on the show and a blogpost on mediafunhouse.blogspot.com), who earned money in the Sixties and Seventies by doing television work. One such item is the very short-lived TV series “Vive le cinema,” which was shot in 1972. The host for the premiere episode was the late, ineffably great Jeanne Moreau, who was to interview filmmakers and performers about the latest items being made. (In amongst her interviews is the one of greatest-ever American filmmakers and various French directors and performers.) Slid into the middle of the program is Jerry Lewis, who is in France to promote his upcoming film The Day the Clown Cried, which he was about to shoot in Sweden – he spoke to Moreau after having had a press conference in the Cirque d’Hiver (where the circus scenes for Clown were shot). The chat is conducted in English but overdubbed in French – I patiently typed out the proper English (computer translations get a general idea but destroy the proper nouns and pronouns) for several hours to get this 11 minutes of footage onto the Funhouse to potentially close out my adventures in Jerry-land (which I thought had ended in the past few years when I did translations of, and readings from, three French books on Jerry; nothing can deplete your energy like Jer….). Thus, Funhouse viewers will have the exclusive pleasure of seeing a Jerry interview replete with images from his binder of notes and designs for Clown that hasn’t aired anywhere since 1972 (and has never been seen on these shores), along with a short selection of telethon clips from the late ’90s (when Jerry was still in fine form, insulting donors and breaking down in tears).

1550.) Vintage: Part two of my ongoing tribute to Robert Aldrich moves into the 1960s, the decade that saw his two biggest box office hits. I start out with a discussion of the joys and motifs of his work and with one leftover from the Fifties, the vastly underrated Ten Seconds to Hell (1959) with Jack Palance and Jeff Chandler as demolition experts who make a very grim wager. From that point on it’s all Sixties (“the gift that keeps on giving and giving and…”) with Aldrich’s extremely popular (and truly iconic) horror thriller/show-biz deconstruction What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and its better-than-you-think follow-up Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964). From that one-two punch of old haunted ladies I move on to his other giant hit, The Dirty Dozen (1967), a seminal “guy movie” as well as an anarchic action pic that paved the way for The Wild Bunch and M*A*S*H. And, because Aldrich was indeed a trailblazing independent filmmaker, I close out with the two films in which he invested his “Dirty” money. Both are about actresses ground down and destroyed by show-biz – the first is the truly dark and arch The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968) and the second is the groundbreaking lesbian drama The Killing of Sister George (also ’68), which was given an “X” rating when it came out. George is indeed dated but is still another fascinating Aldrich portrait of a character whose life is out of her control.

1551.) We return confidently to the “you ain’t seein’ this anyplace else” dept in the Funhouse, with a second (and last) segment from Jacques Rozier’s virtually unknown 1972 TV doc “Vive le cinema,” with English edited by yours truly. This segment finds host Jeanne Moreau interviewing her good friend Orson Welles – who is on the program theoretically to promote his coming films “Don Quixote” (or as Orson himself calls it, “When Are You Going to Finish Don Quixote?”) and “The Other Side of the Wind.” Those topics do come up, but Orson also fills the half-hour segment with stories of his childhood, his inventor father, his beginnings as an actor, and some on-set stories from his earlier films (including Othello and The Trial). The stories are told in the grandest style, as one would expect from the “boy genius” turned brilliant raconteur, with a rapt audience onscreen (the one and only Ms. Moreau). Perhaps some of the stories aren’t really true (as when he speaks about being a sci-fi and mystery writer in Spain who took up bullfighting as a hobby), but it doesn’t matter, as the stories are told so wonderfully they become little cinematic journeys of their own. I’m proud to have present the U.S. TV debut of this material (as I was with the preceding “Vive le cinema” segment featuring Jerry Lewis talking about his “upcoming” The Day the Clown Cried). Thanks to friend Paul Gallagher for finding the film and for help with the subs on the Orson segment.

1552.) Returning to a favorite cinematic deity, this week I review and show scenes from a recent documentary about none other than Uncle Jean, Godard, seul le cinema (2022). This documentary was finished before JLG died so it contains no ruminations on his death, but director Cyril Leuthy does do what few other Godard docs have done – namely, lend equal importance to the work JLG did after 1968, from his radical Dziga-Vertov group period through the Eighties “comeback” through Histoire(s) du Cinema. In the process, a number of French critics and biographers weigh in on Godard’s methods and unique behavior; also heard from are some of his actresses, from Marina Vlady and Macha Meril to Hanna Schyulla and Julie Delpy.

1553.) Vintage: In the third and last part of my tribute to the work of the late, great Robert Aldrich, I tackle his Seventies output, which found him making more “guy movies” while still delivering pointed political messages and terrific updates on old genres. Among the genre updates are his take on gangsters (The Grissom Gang with the late Scott Wilson), the Western (Ulzana’s Raid with the amazing Burt Lancaster), the sports picture (The Longest Yard with Burt Reynolds), and the film noir (Hustle with Reynolds and Catherine Deneuve, and a wonderfully evil Eddie Albert!). Also included are discussions of, and clips from, his memorable chronicle of hobo living in the Depression (Emperor of the North Pole) and his final masterwork, the political thriller Twilight’s Last Gleaming. Aldrich did some amazing work in the Hollywood’s period of “maverick cinema” – despite being a few decades older than the mavericks, he fit right in, because of his skills at subverting genres, spotlighting memorably tortured characters, and crafting haunting imagery.

1554.) Once more to the “you ain’t seein’ this anyplace else” department, I offer a review of, and scenes from, a “missing” (in the U.S., at least) Lars von Trier comedy about his years at film school. The film is titled The Early Years: Erik Nietzsche, Part One (2007) and was not directed by Lars but was scripted and produced by him, features his own first films, and is narrated by him. In the process, we get a view of his early desire to film nature and the way that his film school experience moved him on to genre experiments — plus dealing with the egos of his teachers (all filmmakers slumming as profs) and his fellow students (who served as both his rivals and his crews). The film features performers from other von Trier productions (most notably The Kingdom) and does actually provide us with an interesting look at how the development of a filmmaking persona aids the student in their quest to get noticed by the faculty and the people who will employ them when they get out of school. All this, and how a dolly (the camera-bearing kind) can be an intoxicating lure for a young student….

1555.) Another journey into the “you ain’t seein’ this anyplace else” department, for the “lost” film by the great Aki Kaurismaki, to celebrate his return to filmmaking this very year. The film in question is the 1989 adaptation of a famed Sartre play, Dirty Hands, which Aki made for Finnish television. The fact that this is a telefilm, and the fact that he was adapting a play he wanted to do justice to, meant that this particular film lacks the deadpan humor of Aki’s personal output. It still has Aki’s lean, low-key style, though, spotlighting his great ensemble of actors — led by the two most famous, Kati Outinen and the late Matti Pellonpää — and his visuals, which put eye-catching lighting patterns into otherwise bleak spaces. Set during WWII, the plot finds a loyal “Proletarian Party” member (Pellonpää) taking on the mission of killing the party leader, who wants to build a coalition with the fascist and bourgeois factions in the country. Dirty Hands is never included in Kaurismaki retrospectives (perhaps because he said he never got to edit it, except when he snuck into the TV production building late at night); it is far from his best, but shows what he can do with an exceptional play, delivered to rather conventional producers.

1556.) To celebrate Halloween and the release of a Criterion set of Tod Browning films: Vintage: To further dip ourselves into the Halloween spirit, this week I present the second and final part of my tribute to Lon Chaney Sr., the “man of a thousand faces.” In this episode I focus strictly on the late 1920s, when Chaney made most of his memorably grim character studies, many directed by the sublimely twisted Mr. Tod Browning. Chaney’s portrait gallery of tormented souls includes a number of physically handicapped individuals, but also men doting on younger women who serve as surrogate daughters and also forbidden objects of desire. Lon was indeed a master-sufferer onscreen (and thus a superb silent-movie actor), and in the late Twenties he jumped from role to role, forging an amazing body of work that included bizarre crime dramas (The Unholy Three), character pieces (the Russian revolution tale Mockery, the Asian drama Mr. Wu), and some of Browning’s ultimate views of warped humanity and emotion (The Unknown, West of Zanzibar). Chaney worked with many different directors, but he truly was, according to Sarris’s categorization, the true “auteur” of the films he appeared in.

1557.) Once more visiting the “You ain’t seein’ this anyplace else” department, I present a review of, and scenes from, Nick Millard’s very bizarre Dracula in Vegas (1999). Millard (who used the name “Nick Philips” for most of his movies) was a filmmaker who mostly made exploitation pics in the softcore and horror genres. Some of his pics were what is called today “micro-budgeted” and that is the case with Vegas. In this instance he was intentionally camping it up, but his having used actors for whom English was a second language created yet another level of campiness that makes the picture even sillier. (We’ve explored the “people with foreign accents talking to each other” approach to comedy before, when we talked about Paul Morrissey on the Funhouse.) The plot is a negligible one about a young member of the Dracula family moving from Transylvania to Vegas and falling in love. The cast members include Nick himself (in a cameo), Nick’s mother (possessing a thick Latin-American accent), Nick’s wife’s nephew (the star, a German playing a Transylvanian), Nick’s wife (German), and what are seemingly a bunch of aspiring model-actresses (young women) and standup comedians (older men). It’s not a typical Nick Millard movie (those are incredible studies in micro-budgeted moviemaking — and shoe/boot fetishism if it’s a softcore pic), but it’s a fun one to present to acknowledge his passing late last year.

1558.) Access HQ screw-up: previous episode reshown.

1559.) Vintage: Part one of my interview with cinematographer Caroline Champetier, who has done brilliant work with a host of the greatest filmmakers working in France over the past 35 years. This part of our chat begins with her discussing the somewhat recent films she was doing Q&As for at the Alliance Francaise. The first is Anne Fontaine’s fact-based WWII drama Les Innocentes (2016) and the second is Leos Carax’s triumphantly imaginative and strange Holy Motors (2012). We talk about one of the most flawlessly shot scenes in the latter and she discusses her high-def camera of choice. From there we move backward to the beginning of her career, when she was an assistant to the great d.p. William Lubtchansky (a great collaborator of Rivette). We talk about her work on Chantal Akerman’s 1982 film Toute Une Nuit (like Holy Motors, it’s a journey through one evening; although in this case it’s taken by many different characters) and Daniele Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s ultra-deadpan adaptation of Kafka, Class Relations (1984).

1560.) Vintage: Part two of my interview with the great French cinematographer Caroline Champetier. In this section of our talk, I asked her about two of my all-time Funhouse favorites. First up is a discussion of her work on films and videos with the inimitable Uncle Jean (aka Jean-Luc Godard) over a period of a half-dozen years. I asked her to talk about the comedic “Uncle Jean” character he has played in several films (including two that she shot). She also addressed his reputation as “a master of lighting” (she had a very interesting answer to that). We talk about his indoor and outdoor shoots, as well as the time that she was utilized as an (unbilled) actresss in one of his fiction films. From there we move on to her work with Godard’s “new wave” comrade, Jacques Rivette; Champetier was one of the two cinematographers on Rivette’s great “comeback” film Le Pont du Nord (1980). She talks about that shoot, which was a truly minimalist, extremely “new wave” affair. We close out on a discussion of her work shooting Rivette’s The Gang of Four (1989) on her own – the film is a combination of genres (character study, thriller, political drama), in the classic Rivette fashion.