1561.) Vintage: The third and final part of my interview with the great French cinematographer Caroline Champetier covers a lot of ground and still doesn’t put a dent in her amazing filmography. First off we talk about her frequent work with a performer, namely the legendary Jeanne Moreau. From that we move to one of the directors she’s worked with numerous times, Benoit Jacquot, and the film of his that is her favorite, A Single Girl (an experiment in telling a story in “real time”). From that we move on to her work with filmmakers Jacques Doillon and Margarethe von Trotta. The last filmmaker we discuss is Champetier herself, who has directed and shot a handful of features, including a telefilm biopic about the Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot. I’m glad to have discussed a broad range of Champetier’s work with her – she’s done cinematography for some of the greatest films of the last few decades.

1562.) The Funhouse has a long history of doing Deceased Artiste tributes to the people I love. This week it’s the late, great actor Alan Arkin (who also wrote and directed). In Part 1 of my tribute to Arkin I cover the years 1966 to 1975, in which he started out with three film chameleon-like portrayals of very different characters. Leaving out his not-well-scripted turn as Inspector Clouseau, the trio of great films find him playing: a confused Russian sailor, a villainous hipster, and a deaf mute in a small Southern town. After that, Arkin continued to play “deep” character parts, but also played with his own persona, esp. in his starring role in Catch-22 directed by Mike Nichols (amidst an all-star cast of neurotic actors). Along the way there were gems of the “maverick Seventies” like Jules Feiffer’s pitch-dark Little Murders (which he directed and had a supporting role in), a revved-up buddy cop movie (Freebie and the Bean), and an unusual road movie (Rafferty and the Gold Dust Twins). Part 2 to come!

1563.) Screw-up at Access Playback!

1564.) To celebrate the holiday season and commemorate the passing of William Klein (yes, it was several months ago, but we never forget the artists we love in the Funhouse), I present an episode built around Klein’s last feature, Messiah (1998). Klein decided he wanted to “illustrate” Handel’s classic with devotional imagery – thus, we have three kinds of footage seen in this film. The first are images of American excess, including Xtian conventions, celebrations in Vegas, and kitsch (a bodybuilder “for Christ”); the second is comprised of religious ceremonies from countries all over the world (some of the footage shot by Klein, some licensed from other sources); the third, which is perhaps the most memorable but is dropped midway through the film, are local choirs singing pieces from the Handel original. (A “regular” classical choir is singing the piece throughout, in English with French subtitles – the film was funded by different production entities, but most of the money came from France.) Klein does indeed tip his hand at one point and show sped-up traffic (which seems like a nod to Godfrey Reggio and his Glass-scored chronicles of human activity). Klein’s film thus moves through the landscape of some of his incredible photography – the culture of cities (as often tacky as it can be) and the faces of their inhabitants (shown here in a beautiful montage of couples at a Texas open-air event).

1565.) Vintage: In tribute to the passing of Agnes Varda, I present a discussion of, and clips from, her 2011 arts-cable miniseries From Here to There. Varda’s fiction films from the Sixties through the Eighties are superb; after that period, she made documentaries that were either sublime (The Gleaners and I) or charming but scattered, as with this five-part video diary. In it we see Agnes move from country to country, receiving honors for her films and interacting with her favorite artists. As could be expected, the interactions that are the most fascinating to me are with other filmmakers. Thus, her time spent with Chris Marker in his studio is the most vivid portrait of the man that exists on video (albeit with him still located outside of camera range); her reflection on the sale of Ingmar Bergman’s possessions is equally moving. But even Agnes’ uneven work is better than most mainstream filmmakers’ best pictures, so tonight we pay tribute to her moving from “here to there.”

1566.) The second and last part of my Deceased Artiste tribute to Alan Arkin finishes up his “golden” years (when everything he was in was worth seeing), plus some stray later projects I’m fond of. The chronology picks up in ’75 and features two of the films he was in that were box-office hits – The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, where he gave a nuanced performance as Freud, and The In-Laws. He was a producer of the latter, which shows how influential performers could still be in the creation of relatively small films (for big studios) even after the shift to “tentpole movies” for young minds. (But before Heaven’s Gate.) His re-teaming with Peter Falk is also excerpted but it was not a hit; in fact, Big Trouble (where Andrew Bergman left the project as director and John Cassavetes came in to fill the void; it was his last film) was barely released. The Eighties, Nineties, and so forth yielded a few good film roles for Arkin, but the 21st found him both winning an Oscar for Little Miss Sunshine (not featured here; you can find it) and also appearing in senior buddy comedies that were instantly forgettable (and impossible to distinguish from each other). I have substituted a bonus (rare) final clip of him just a short time ago doing something closer to his heart.

1567.) In the “You Ain’t Seein’ This Anywhere Else” dept of the Funhouse, I present an episode devoted to Goldstein, Philip Kaufman’s 1964 debut as a filmmaker. Directed with Benjamin Manaster, the film is an episodic journey that includes dramatic and comic scenes, all grouped around the idea that an Elijah-like prophet (Lou Gilbert) has emerged from the water and is wandering around the streets of Chicago. There’s an allegorical, free-form aspect to all of this, inspired (according to Kaufman) by the French New Wave and the films of Cassavetes and Shirley Clarke, but the scenes featuring certain characters outline a plot that is very much of its time – including a thread in which an aspiring sculptor gets his girlfriend pregnant and she gets an illegal abortion performed by two traveling (and very chatty) abortionists. What makes Goldstein so special, though, besides its Chicago location shooting, is the casting of a number of Second City legends — Del Close, Severn Darden, Anthony Holland, Jack Burns, and the mother of it all, Viola Spolin — as well as novelist Nelson Algren, who tells an unusual story about a ball player to our sculptor antihero. The film is currently out of print on disc and has yet to show up in the usual arthouse spaces.

1568.) Spotlighting yet another “maverick era” film that has been underseen since it came out, I present an episode discussing and excerpting T.R. Baskin, a 1970 “small movie” that was made by a major studio with a seasoned but mostly conventional director (Herbert Ross) at the helm. The film is another one of those little character-study gems made in that era, which makes no grand statement and isn’t “epic” in any way, but ends up saying more about relationships and feeling lonely in the process. The plot revolves around a wisecracking (but very deadpan) young woman (Candice Bergen) who moves to Chicago to start a life and ends up encountering chatty people (and loneliness) at every turn. Peter Boyle is characteristically perfect as a traveling salesman “looking for a good time” who has been given her number, and James Caan is the lover that was “meant to be” but wasn’t. The script by Peter Hyams functions like a novella in its delineation of character and place (with the Chicago locations helping greatly in that respect); Ross’s only stylistic flourish is to mimic the paintings of Edward Hopper (something he later did in arguably his best picture, Pennies From Heaven). The performances are sharp (including Marcia Rodd as T.R.’s newfound best friend), the dialogue is revealing and funny, and the overall impression is of seeing “moments from a life” – something never done better (and more consistently) in Hollywood films than in the early Seventies.

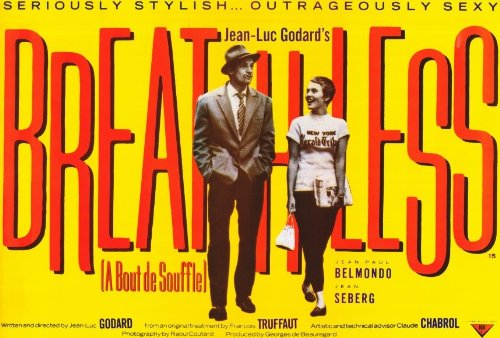

1569.) In the “You Ain’t Seein’ This Anyplace Else” dept, I return to the work of the young Philip Kaufman for his second film, the comic-book, pop-art comedy Fearless Frank (1967). It’s an incredibly silly picture that happens to have a terrific cast, eye-catching Chicago locations, and visuals that are surprisingly both Godardian and Kirby-esque. The plot concerns a benevolent scientist (Severn Darden, pictured) who brings a young man (Jon Voight, in his first movie role) back to life as a superhero to fight the ruthless (and all-made-up) sidekicks of a crime boss (Lou Gilbert, the star of Kaufman’s Goldstein). These villains are holding a femme fatale (Monique van Vooren) hostage and are played by, among others, Ben Carruthers (Cassavetes’ SHADOWS), the young David Steinberg, and novelist Nelson Algren (!). The visuals are indeed the whole show as Kaufman both mimics comic books (the work of Kirby is brought to mind by the sight of Voight in his silver suit eliminating the villains) and the French New Wave – most prominently Godard, who had made widescreen films with bright primary colored images (Pierrot Le Fou, Made in USA) a year or two before Kaufman made Frank.

1570.) Vintage: Presenting scenes from another “film you ain’t seein’ anyplace else,” this week I highlight sequences from the French romantic comedy Adorable Liar (1962), directed by Michel Deville. The film is charming but slight, but it is worth highlighting because of its cast. Its two stars, Marina Vlady and Macha Meril, plays sisters from the country who are flirting with the men they meet in Paris. (Marina’s character is a liar who is eventually hoisted with her own petard.) The interesting thing with that pairing is that both women later worked for Funhouse favorite Jean-Luc Godard (separately but memorably). Other favorite performers appear in the film in small roles, including the great Michael Lonsdale and Pierre Clementi (whom we will be saluting in future episodes).

1571.) A brilliant British farce hits the Media Funhouse, in three distinct parts. The show airs late Sat/early Sun at 1:00 a.m. EST. (Click link below and in the comments.) This week: Can deconstruction ever be funny? The answer (yes) can be found in the trilogy of plays written by Alan Ayckbourn called The Norman Conquests. This week I begin a series of episodes devoted to this trilogy, which was made into a BBC miniseries that aired in the U.S. on PBS back in the long-ago that was the late Seventies. The series presents a weekend in a country house, in which six people endure each other’s presence while (central action here) a randy librarian, played by the utterly charming Tom Conti, tries to sleep with the female members of the family. He’s married to one sister (Fiona Walker), has planned a weekend getaway with her younger sister (Penelope Wilton) and, during the run of the plays, seduces his sister-in-law (Britcom veteran Penelope Keith). Ayckbourn wrote the three plays so that each one has only one setting (part one is set entirely in the kitchen), and only by seeing all three of the plays does the viewer truly understand what went on over the course of the weekend. In the process, the plays lay bare the construction of a farce — we have characters moving quickly in and out of doors, behavior being based on events we saw previously (or are going to see), and quiet, well-scripted moments of character exposition alternating with broad comic explosions. While this may sound cold and calculated, the result is a very entertaining portrait of some very “on edge” characters, with the whole thing stolen by Conti in a career-making turn as Norman, the very horny librarian.

1572.) The second play in the “Norman Conquests” TV trilogy is the center of this week’s episode. “Living Together” in set, naturally enough, in the living room, and shows us other events from a lively weekend where assistant librarian Norman (Tom Conti) seduces the women in his wife’s family. “Norman” was written by the prolific and influential Alan Ayckbourn, who put together perhaps the ultimate farce and then took it apart, creating three plays in three different settings in the same house. The material is top-notch and so is the cast, which includes Britcom vets Penelope Keith (who won a BAFTA for the “Norman” miniseries) and Richard Briers, and Penelope Wilton (later of “Downton Abbey”). Stealing it all away is Tom Conti in the “breakout” (at least in the U.S.) role of Norman, a man whose only goal is to make the woman he’s flirting with “happy.”

1573.) The third and last play in the “Norman Conquests” trilogy is the subject of this week’s episode. In this final installment, we learn what went on during a very busy weekend in the backyard of the house. The plot – about an assistant librarian (Tom Conti, in his career-making turn) trying to seduce all the women in his wife’s family – continues apace, but here we learn how the story actually ends. You can indeed see and enjoy any of the plays, here presented in their ITV iteration from 1978, without seeing the others, but seeing all three of them in sequence presents you with the full, twisty plotline, plus you can witness a master farceur, playwright Alan Ayckbourn, taking apart his storyline and then piecing it back together again. The cast includes a few familiar faces from Britcoms (including Penelope Keith, who won a BAFTA for the “Conquest” TV trilogy), but Tom Conti is the undisputed star, as he gives life to the charming, but utterly ethic-free, Norman.

1574.) Delving into the work of a post-French New Wave filmmaker whose films aren’t known in the U.S., I present a discussion of, and scenes from, the 1974 film Femmes Femmes. The film is quite unusual, as it is a b&w comedy-drama involving two actresses (Hélène Surgère and Sonia Saviange) who are roommates and are both falling into alcoholism; their oddest connection is that they were both married (at different times) to the same man. Vecchiali constructed the scenario for the performers, whom he allowed to ad-lib, and the result is a very unpredictable mix of humor, musical numbers (!), intentionally histrionic acting, and salutes to old movie stars — in the form of shtick done by the actresses and their wall-hangings, which consist of glamour headshots of French and American stars of the 1930s and ’40s. Femmes is a unique movie (Pasolini was one of its first big fans) that provides a portrait of aging women (the actresses playing these “old” actresses were in their 40s/50s) that harkens back to the glamorous past of cinema and yet relates to the “women’s lib” era in which it was made, as scripted and directed by an openly gay middle-aged filmmaker.

1575.) I’m proud to offer up the U.S TV debut of scenes from a film that is a veritable “missing link” in the career of the great Aki Kaurismaki. The Liar is a 1981 film by his brother, the Finnish innovator Mika Kaurismaki, which stars and was co-scripted by Aki in tribute to Uncle Jean (aka Jean-Luc Godard) and the great New Wave actor Jean-Pierre Leaud. Aki plays “Ville Alfa,” a bush-league seducer, scam artist, and sneak thief who moves through various situations by the skin of his teeth. Made for Mika’s film studies at a Munich film school, the film has gorgeous b&w widescreen visuals (which I hope can be reproduced all right on Manhattan cable) and some nicely deadpan performances by the cast, led by Aki doing what he deemed his “impression” of Leaud from films like Masculin-Feminin. The film has never been released in the U.S. and gives us a rare view of the work of Mika (the student filmmaker) and Aki (at that time studying journalism, not film) when both were young men who seemingly enjoyed the pleasures of Aki’s characters – smoking, drinking, and listening to rock ’n’ roll.

1576.) I’ve waited several years to show scenes from the most prominent of Fassbinder’s “missing” films (which amount to three theatrical features and a handful of telefilms) and have decided that now is the time to discuss and feature scenes from it — since nothing is on the way in terms of an American release. Clearly the American rights are caught up in some bind, because a restored print of the film, Lili Marleen (1981), is on Blu-ray in Europe and it just happens to be the English-dubbed version. (The film was shot by Fassbinder in English; despite that, certain short moments in the restored version revert to German.) The film was a work for hire for RWF; Hanna Schygulla was sought for the lead and she said she would only do it if he directed. It is thus a peculiar item that at once looks and sounds like a Fassbinder film, but it also has a very conventional plot structure and heightened emotions that can be looked upon as his approximation of tropes from the Hollywood biopic/WWII movie model, or his satirizing them. Hanna plays a fictionalized version of Lale Andersen, the man who made the song “Lili Marleen” a hit in Germany during the war. We watch as she and her Swiss Jewish orchestra leader boyfriend (played by Giancarlo Giannini) are broken apart by the Nazis but keep drifting back together. The film has a cornier feel than Fassbinder’s personal work, but it does benefit from three elements that always distinguished his films: the absolutely beautiful cinematography of Xaver Schwarzenberger (who did all of RWF’s films after Michael Ballhaus started working in the U.S.), the atmospheric music of Peer Raben, and the acting of the Fassbinder ensemble. Schygulla gives a very “up-tempo” performance here that is odd with her other work, but she was at the height of her beauty at this time and the height of her fame — and was indeed Fassbinder’s very own Dietrich, as shown in the musical sequences here. (Where Hanna did her own English dubbing.)

1577.) This week it’s the second and last part of my discussion of and tribute to the most prominent “missing” Fassbinder film, Lili Marleen (1981). The film was never on VHS, never mind DVD or Blu-ray, in America so it has only been seen since ‘81 at comprehensive retrospectives of RWF’s work (and on foreign releases). The film is very different from the “BRD Trilogy” that Fassbinder made around the same time, in that it was a work for hire that is played in a “high register” – Fassbinder had Hanna Schygulla laugh uproariously, cry emotionally, and deliver her lines in an over-the-top fashion that has led one critic to say RWF was “sabotaging” the material. It feels instead like he planned certain scenes as satires of Golden Age Hollywood biopics and WWII spy dramas. The most notable things about the picture are the gorgeous imagery crafted by cinematographer Xaver Schwarzenberger, the emotional score by Peer Raben, and the performances by members of Fassbinder’s ensemble. In this film we have the indelible image of a top-secret, late-night espionage discussion in a car containing Hanna, Udo Kier (wearing a scarred face prosthetic), and RWF himself.

1578.) For the annual Easter skewering of Cwazy Cwistian Cinema, this year I go back to a motherlode that received a pristine restoration in the past year. Thus, I offer not one but two episodes about the “Estus Pirkle” trilogy directed by Ron Ormond and created by the Ormond family of Nashville, Tenn. I formerly featured two of these three films on the show when they were available in scratchy-looking 16mm copies on VHS; now they have been computer-perfected to be blemish free in the 21st century! I discuss that phenomenon at the outset of this episode (part one of 2), the “box sets of shlock auteurs” that offer us frighteningly cleaned-up copies of entertaining trash cinema. (Looking better than they ever looked when the films were new and playing in theaters — or, in the case of these films, in Southern churches.) The convenience and collectability of having all the films together in one box is a virtue; the computer restoration jobs (which are bizarre-looking, as they render every error with perfect crystal clarity) not as much. Then it’s on to the first in the Pirkle trilogy, the dauntingly titled If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? (1971). The film is an absolute classic of Christian exploitation, as it focuses on what Dr. Estus Pirkle (camera-aware apocalyptic preacher) saw as the impending overrunning of America by Communists. As in all three films, co-scripter Pirkle gives us precise details (that aren’t in the slightest bit fabricated to sound dramatic) about when and how the Commies will overtake us. He also decries those aspects of American life that he feels convey loose morality (sex education classes, children’s cartoons, boy-girl dancing). It’s a torrid story, and one that’s conveyed with an H.G. Lewis level of gore, because there’s no rule about avoiding graphic violence when you’re trying to scare someone into loving Jesus.

1579.) The second and last episode about Ron Ormond’s “Estus Pirkle trilogy,” in which I discuss and show clips from the second and third of the movies. Pirkle was a preacher who recruited Ormond (who worked hand in glove with his wife and son on his productions) in the 1970s to make films out of his way-out apocalyptic sermons. The movies discussed here are The Burning Hell (1974) and The Believer’s Heaven (1977), which detail Pirkle’s no-nonsense (or pity) versions of punishment and redemption. Ormond had previously made all kinds of exploitation pictures and so he used his background in no-budget horror for Hell, offering us a glimpse of a dark, fiery realm where the people are covered in oil and constantly tortured in one way or another. The Hell movie, on the other hand, finds Pirkle describing a tacky vision of splendor that bathes the good Xtian in clouds, robes, shiny floors, big doorways, and a mixture of “precious stones” that Pirkle runs through in one truly odd sequence. Among the unusual elements in this duo of flicks is the fact that the cast flew to the Holy Land and Hawaii (?) to shoot certain scenes (featuring Biblical characters speaking with deep Southern accents) and that Pirkle’s sermons throughout contain an incredible number of specific details about Hell and Heaven (population, decorations, durations of torture or pleasure) that he claimed were all true. Given that “Dr.” Pirkle is no longer with us, one assumes he discovered which of his trivia facts was indeed true….

1580.) I’ve presented a lot of “Things You Ain’t Seein’ Anyplace Else,” but this week’s offering is indeed extra-special. It represents for me the happier side of man who is often depicted as an acerbic, gloomy, doomed soul – Lenny Bruce. Lenny is used as a legal reference these days more than he is discussed as a comedian and an entertainer. In the latter capacity, during a period when he was commercially controversial (different from his later unemployed controversial), he got an offer from the NYC station WNTA to make a special for their series “One Night Stand.” So, one night in April 1959 Lenny had a 90-minute special, “The World of Lenny Bruce,” air opposite Paar’s “Tonight Show” on WNTA (a commercial station, later to become WNET and part of PBS) featuring whatever guests he could gather (and afford), his own standup, and most jarring and welcome of all, home-movie footage of the places he loved in Manhattan. I’m hoping to make two episodes out of the copy I was able to obtain of this special; for this first episode, I delay showing his standup (since that was used in Fred Baker’s Lennny Bruce Without Tears) and instead focus on him introducing three acts and talking directly (and, at one point, singing!) to the viewer. The musical acts he booked were, unsurprisingly, all jazz performers. But there was one gentleman that Lenny was thrilled to showcase (throughout the segment he’s grinning broadly and brimming with enthusiasm): a man he saw as a kid at Hubert’s Museum, Professor Roy Heckler, a master of the once-frequent sideshow attraction, the flea circus.

1581.) One of the films that I waited several decades to see, Il Pap’occhio (read: Eye of the Pope) is an episodic farce that recounts the efforts of a TV host-producer, played by real-life TV host- producer Renzo Arbore, to find people to appear on a new “Vatican state television” network. Along the way we see a variety of ridiculous acts and several guest stars — only one of whom, Mariangela Melato, will be known to U.S. cinephiles. While Arbore’s character keeps auditioning oddball talent for the new network (including a very special choir), we also witness efforts to teach the Pope proper Italian (this was during the time of John Paul II, who evidently retained his Polish accent while speaking the Mother Tongue) and different sequences involving Arbore’s two world-famous discoveries (who flourished while on his Sunday night TV show), Isabella Rossellini and Roberto Benigni. The former makes a joke relating to her mama, while the latter does a few comic bits that were clearly improvised on the spot (including one where he’s repainting a part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling). Also showing up in this collection of bits and pieces is Isabella’s then-husband, who is seen in a cameo appearance “directing” the first night of the new network — the bearded (the sign of quality!) Martin Scorsese.

1582.) Vintage: Let’s venture once again to the swingin’ Sixties in France, this time for a satire on the packaging of pop stars that is part spectacle, part theatrical “happening,” and all nasty abuse of the music industry. The film is Les Idoles (1968), and the writer-director is Marc’O, a key member of the Lettrist movement of the Fifties (for more info, check out my review of Isidore Isou’s “Venom and Eternity” on YouTube) and noted playwright-director. Here he keeps intact the cast of his original play, each performer incarnating an interesting (and creepy) type of pop star: Pierre Clementi plays a “tough kid from the streets” who has become a rocker; Bulle Ogier (in her first significant movie role) plays a ye-ye girl whose delivery is grating and whose lyrics are quite perverse; and Jean-Pierre Kalfon is a fortune-teller turned rocker who specializes in agonizingly self-deprecating psychedelic tunes (also sung out of key). Marc’O thus is able to spoof different kinds of stardom and different record-company gambits (including the sudden romance of Clementi and Ogier’s characters and the excusal from military service of Clementi). The film is intentionally abrasive and in-your-face (witness guest star Bernadette Lafont’s incarnation of “the Singing Nun”), and it shares the mod/psych look with items we’ve debuted on the Funhouse (especially the films of William Klein and Anna).

1583.) Vintage: Filmmaker Dusan Makavejev died several months ago, but we don’t have deadlines for career appreciations in the Funhouse. And so this week I present part one of a series of shows dedicated to his work. In this episode you get the cream of the crop (and more from the decade that is the gift that keeps on giving and giving and…) with his first four features. The first two, which are both brilliant, have shown up on the late night TCM foreign movie slot, and are perfect examples of the kind of slyly subversive things that could be made in (some) communist countries in the Sixties; they also outline Makavejev’s most familiar character – a young woman who is sexually and politically liberated, who winds up being “punished” by a man she encounters. Makavejev’s third film, Innocence Unprotected, is a brilliant hybrid creation – the first Yugoslav talking feature (a corny drama featuring a strongman), intercut with documentary footage of the participants as seniors and newsreel footage from the time (plus, well, just some weird stuff Makavejev discovered). This episode ends with his most famous film, WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971), an amazing hybrid of documentary (about Wilhelm Reich), fiction, blazing satire, NYC troublemakers (Jackie Curtis walking along the Deuce; Al Goldstein and Jim Buckley running “Screw” mag), and extremely sharp social commentary about sexuality. Plus MNN stalwart Tuli Kupferberg running through the streets of NYC dressed as a soldier, shooting off a toy gun….

1584.) This week the “You Ain’t Seein’ This Anyplace Else” department becomes the “You Ain’t Seein’ Anyplace in the Biggest English-speaking Countries” department, as I discuss and show scenes from Roman Polanski’s 2023 farce The Palace. So far, the cancellation of Polanski’s work in the U.S. and the U.K. (and its one-time and current colonies) has denied viewers in those locales three of his films. I’ve shown scenes from the first two on the Funhouse (with J’Accuse being a late-period masterpiece for Polanski) and this time out it’s scenes from his Millennium comedy, which was declared his worst-film-ever by some critics (which is surely wrong, because nothing he’s made will ever descend to the level of Pirates). The film is a *broad* comedy that is far from Polanski’s great work, but it is not as godawful as European reviewers contended. Scripted by Polanski, his old friend Jerzy Skolimowski, and Eva Piaskowska (Skolimowski’s wife), the film follows various inhabitants at an extremely posh Swiss hotel as they prepare to ring in the Millennium on New Years Eve 1999. The stars include Fanny Ardant, John Cleese, Mickey Rourke, and many others, and (like many BIG farces) actually scores more laughs from the toss-off material or tangential gags than the main plotlines. It is still of interest because Polanski is one of the few master filmmakers from the Sixties era working today, and here he evokes the mix of European and American mega-rich people with a proper mix of fascination and disgust.

1585.) Vintage: The last part of my Deceased Artiste tribute to filmmaker Dusan Makavejev focuses on the film that “halted” his career for a while, and the ones that appeared after his 1981 comeback with Montenegro. The 1974 film Sweet Movie is one of the great “outrages” in film history – a work that combines memorable imagery and sharp satire with strange indulgences and scenes that are included to “test” the audience. His two most normal pics, The Coca-Cola Kid (1985) and Manifesto (1988), found him injecting his trademark concerns (sexuality, the juxtaposition of human and animals, strongly committed women characters) into quite linear scripts, with the result being quite entertaining (but still weird) filmmaking. His final feature, Gorilla Bathes at Noon (1993), is a sad shadow of Makavejev’s best work, reflecting back on the Soviet Union at the moment that the former Yugoslavia was torn apart by violence.

1586.) The second and last episode comprised of scenes from the hidden TV special “One Night Stand: The World of Lenny Bruce.” The show was commissioned by a local NYC channel (which later morphed into WNET) and ran 90 minutes opposite the Jack Paar version of “The Tonight Show” in April 1959. Lenny was allowed to do anything he wanted, so we see some of his standup (which I’ve mostly edited out, since that particular segment appears in the first major on documentary on him), some home movies he shot of his favorite places in Manhattan (the Deuce, the Lowest East Side, the Apollo Theater, etc), and musical guests. The last-mentioned does contain one gospel act but for the most part Lenny invited jazz performers. In this episode I show Lambert, Hendricks and Ross, and Cannonball Adderley (whose combo plays while we see film Lenny shot at MoMA). The special is incredibly rare and I’m proud to share it with late-night viewers who, were we transported 65 ago, might have lived in Lenny’s world.

1587.) Vintage: Part three of my three-part tribute to Deceased Artiste Dusan Makavejev focuses on just one film, his “comeback” picture Montenegro (1981). The film is different from his earlier works in that it tells just one story, in a linear fashion. It shares with its predecessors a warped sense of humor and wonderful surprises from other media – in this case, the fact that he frames the plot with Marianne Faithfull’s perfect rendition of Shel Silverstein’s “The Ballad of Lucy Jordan.” The storyline centers around a well-to-do American housewife (Susan Anspach) living in Stockholm who is slowly losing her mind until she ventures away from her husband and kids for a little “vacation” in the bosom of a Slavic community in Sweden where the strangest things are commonplace. The film’s focus on sex links it to Makavejev’s work from the Sixties and Seventies, but in this context it was even more subversive, since this film was shown in a broader variety of arthouses and was a critically acclaimed film shot in English.

1588.) Dipping back into the deep pool of amazingly odd films made by Funhouse interview subject Marco Ferreri, this week I discuss and show excerpts from his first Italian feature, The Conjugal Bed (Italian title: L’Ape Regina, aka The Queen Bee, 1963). This is a relatively light allegory about male-female relationships but it still has the sting of Ferreri’s later allegories about the end of the Sexist Male and the coming of the Liberated Female. Here, sports-car salesman Ugo Tognazzi falls for a beautiful woman (Marina Vlady) who lives with her very large family. Upon marrying her, he lives with said clan but is still eager to have sex with his new bride – although he seems to be having trouble. He takes pills and does therapies (and spiritual retreats) to help him with his problem, but it’s only when he’s challenged by his wife’s bitterest insult (that he is old — throughout the film Ugo’s real age of 40 is constantly mentioned) that he is able to have vigorous sex again. The resulting changes in the couple’s dynamic (which are *not* in favor of Ugo) are what constitute Ferreri’s message. That said, one can enjoy the film simply as an Italian sex farce with two very appealing leads (and a “best friend” character who looks a lot like Federico Fellini; that’s because he’s played by Riccardo, Federico’s brother).

1589.) Vintage: Part one of my multi-part Deceased Artiste tribute to filmmaker/cinephile Bernardo Bertolucci focuses on his first three films. He came on the scene at age 21, a published poet and movie fan who had a great sense of storytelling and a brilliant visual sense. The first film, The Grim Reaper (1962), is a kinetic, atmospheric whodunit that recounts the same incident from different viewpoints. That debut feature, made from a storyline by Bertolucci’s friend Pier Paolo Pasolini, found him forging his own style, which flowered in Before the Revolution (1964). A film that blends the political and the sexual, Revolution is Bertolucci’s first masterwork and it indicates the path he was to follow until the mid-Seventies (and return to in his best pictures after that point, the non-“pictoral” character studies). Plus, it has one of the finer movie buff conversation scenes, prefiguring Scorsese and Wenders. His third film, Partner (1968), is his most Godardian work, an overtly political modern adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s “The Double” that stars fellow radical artist Pierre Clementi in both roles. The film was being made in Italy in May ’68 as the riots were occurring in Paris and it borrows from that energy and boasts some very bizarre, unforgettable imagery.

1590.) Vintage: Part two of my multi-part Deceased Artiste tribute to filmmaker Bernardo Bertolucci covers his fourth through sixth films, all three of which are rightly considered in the top rank of his work. The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) was the turning point, a low-key but brain-teasing adaptation of Borges that finds its protagonist exploring the mysteries of his “hero” father’s murder. The following film is one of Bertolucci’s finest, The Conformist (1970), a magisterial drama set in the Thirties about an informant turning in his Marxist acquaintances to the fascists; whether you’ve seen the film or not, you’ve seen homages to it (most specifically in the first two “Godfather” films). The last film discussed in this episode is the one that made Bertolucci famous (and gave him the ability to make bigger-budgeted films – which turned into both a blessing and a curse), Last Tango in Paris (1972). The film is the first of Bertolucci’s “hothouse” apartment-set films, boasting a superb lead performance from Brando, gorgeous location footage, and fascinating insights into love, sex, death, and (the part everyone forgets) filmmaking.

1591.) Vintage: The third part of my ongoing tribute to the work of Deceased Artiste Bernardo Bertolucci focuses on just one film, but what a film! Bertolucci’s passion project, 1900, is an epic tale of landowners and peasants in 20th-century Italy that is ripe with wonderful performances, some gorgeous visuals and music, and several over-the-top moments that you’ll never forget. The film tells the story of the interaction between the scion of a family of landowners (Robert De Niro) and his best friend, the legacy bearer of a family of peasants (Gerard Depardieu, at his all-time thinnest). The film runs from the birth of the two lead characters – their family patriarchs are played by Burt Lancaster and Sterling Hayden! – through their adults lives, with their respective wives (Dominque Sanda and Stefania Sandrelli). Donald Sutherland gives an unforgettably gonzo performance as the local head of the blackshirts, a fascist so mean he kills animals and children with much abandon. The film is one of Bertolucci’s most ambitious (The Last Emperor is a controlled work next to this one) and is uneven (particularly in the full five-hour international cut, which is now the one on DVD and in repertory) but has some of the memorable moments he ever directed. And, as he put it, he employed “multinational capitalist means [read: money from three H’wood studios] to produce a naive, edifying vision” about the glory of the Communist party in Italy.

1592.) Vintage: The fourth part of my tribute to Deceased Artiste Bernardo Bertolucci focuses on the great films he made after he had a massive box-office success with Last Tango in Paris. The most fascinating entry in his post-Tango filmography is the drama/character study Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man (1981). Ugo Tognazzi stars as a cheese factory owner whose son is kidnapped – and who develops a plan to save his factory once he is told his son has been killed by the kidnappers. Tragedy is a return to Bertolucci’s Sixties roots, with a storyline that is both overtly political and engagingly ambiguous, with Ugo’s character reflecting on the changes in society as he engages in a scam and might well be the victim of a double-cross. Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003) was his final farewell to the Sixties, utilizing the May ‘68 riots as the backdrop to a story of a trio who are cineastes and lovers. The most overlooked later work by BB is his short “Histoire d’eaux” (Story of Water) from the anthology feature Ten Years Older: the Cello (2002); I discuss the short and show it in its entirety, as a tribute to the late, great Signor Bertolucci.