729.) Think back to a time when American cinema was at its most original and unfettered, when the best filmmakers were making their most kinetic and intelligent work with major studio backing, and when the biggest young (and middle-aged) stars seemed to consistently make the right choices about what to appear in (whether or not it made money). Let’s stay in 1972 for a while, just long enough for an episode-long discussion about one of my favorite “small movies” of the early Seventies, Bob Rafelson’s King Of Marvin Gardens. The film has come out on DVD, but it has no “bonus supplements,” so I feel it necessary on the Funhouse to offer what could easily be a commentary track: the first part of my interview with the film’s screenwriter, Jacob Brackman, covers the genesis of the project, the time in which it was made, the strength of its casting, the fact that it pivots around an FM spoken-word deejay, and the choice of the then-dilapidated Atlantic City as its setting. The film is definitely one of the best Nixon-era statements about “the failure of the American Dream,” but it also is amusing, literate, and superbly acted. Oh, and thanks to Mr. Brackman, well-written.

730.) A vintage show this week: I celebrate my birthday this year with a presentation of select clips and reviews of the recent DVD releases of Naked City episodes. The program is notable for its incredible location shooting in the five boroughs and for its sad, nearly grim, noir-style plotting. Based on the 1948 movie of the same name, the show’s only “normal” moments focused on sensitive, Freudian police detective Paul Burke, his gruff boss Horace McMahon, and always chipper sidekick Harry Bellaver; each episode generally spun into high gear when covering the life of a criminal or disaffected city dweller. In this episode, I discuss the show’s “cold openings” where we join the crooks/misfits in media res and try to figure out exactly where the show will go from there. Also discussed are the fledgling stars who appeared on the program, most of whom were struggling NYC theater actors or film stars who had moved down the work-scale, and the noir directors and scripters who moved on to this series after the noir cycle had wound down in the mid/late ’50s. Last up is a discussion of favorite Funhouse actresses as they appeared on the show as mere lasses: Sandy Dennis, Barbara Harris, and the ever-radiant Tuesday Weld. All three starred in particularly grim episodes that can truly be labeled “TV noir.”

731.) Part two of my interview with screenwriter Jacob Brackman, screenwriter of one of the finest “maverick” pictures of the early 1970s, Bob Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens. In this episode, we discuss Mr. Brackman’s friend Terrence Malick, whose gorgeously picturesque Days of Heaven (1978) he produced and worked on as a second-unit director. He reveals how he helped Malick shape the narrative, creating a montage-based picture out of a dialogue-heavy character study. We move from Malick’s sublime effort to a campier affair, 1980s Times Square, Mr. Brackman’s only other produced screenplay. Intended as Robert Stigwood’s “punk” companion piece to Saturday Night Fever, the picture is a strange time capsule of an era that never really was, shot on locations that were all too real and are now very sadly gone, most prominently “the Deuce.” We talk about the core of the pic, which is an implied lesbian relationship between two teenage girls, runaways living a wild (but curiously chaste life) right in Times Square. We then turn to Mr. Brackman’s other career, as a lyricist in the pop/rock/theater world, spotlighting his work in the early 1970s with Carly Simon, and close with, what else, the sublimely low-key King of Marvin Gardens, a true Funhouse favorite and a movie that deserves a bigger cult.

732.) As the holiday season hits us straight between the eyes yet again, I feel it is time to return to the venerable institution of the variety show, and when pursuing that topic, what better personage is there to salute than one of our Funhouse all-time, all-time favorites, Sammy Davis Jr. This week’s slice’o Sammy finds the indefatigable, inexhaustible entertainment machine performing for a German audience on a Deustche TV special, circa 1985. The program, directed by a certain “Rainer Kaffka” (I’m not kidding) is a full-dose of Sam on stage, with two elements included purely for his European audience: extended scatting segments — including the nicest variant on his familiar “kon-chiki-kon-kon” and his old singer and movie-star shtick (he notes that he resurrected the latter because the Europeans “remembered” him for it — perhaps it’s because they were still very much aware of who those American celebrities were). Next up it’s Sam in one of his rare appearances on Dean Martin’s variety series. Sam does a solo tune (an emblematic late Sixties classic) and then it’s medley time (Rat Pack minus one). I close out with a short bonus or two, including a seasonal favorite (sans SDJr) and a clip that links Sam to one of the biggest phenomena of the mid-Sixties.

733.) Our vintage offering this week is a piece of remarkably bad but watchable 1970s TV. I felt I must share the worst incarnation of the Man of Steel ever (and that’s counting the startling no-budget “Turkish Superman”). The usual depictions of Kal-El make him omnipotent, a misfit, and pretty damned boring — in this 1975 TV special It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s Superman, based on a failure 1966 musical, he’s a Spiderman-like neurotic who (ah yes) sings. He is joined in this unwarranted warbling by the rest of the characters in this astoundingly misguided effort, but is played by the only unknown in the cast, a certain David Wilson. The rest of the cast includes name performers from the period, most of them from the TV arena: it’s narrated by Laugh-In Golden Throat Gary Owens, the more-than-lovely Lesley Ann Warren is Lois Lane; Kenneth Mars (always terrific) and Loretta Swit are Clark Kent’s mean colleagues; David Wayne is an evil scientist plotting Supe’s destruction; and a motley assortment of gangsters, played Malachi “False-face” Throne, Al Molinaro, and Harvey Lembeck (Harve’s son Michael, aka “Kaptain Kool” plays a hippie who explains “freak power” to the lunkheaded superhero).

734.) Though the Funhouse lasts a mere 28 minutes, the behind-the-scenes preparations for some episodes can take months in some instances. In the case of this week’s Deceased Artiste tribute to Ingmar Bergman (part two), I thought that, after the last 1960s-focused episode, I could move through the rest of his career in a single, second episode. Then I decided that, since I knew I really did like everything I’d seen of his but had hazy memories of even the most famous titles, I should take a look at a few of the 1950s classics — and then I did something I had sworn I wasn’t going to do. I took a chance on one of his earlier melodramas, a supposedly torrid group of pics that have been written off by most critics and pretty much dismissed by Bergman himself. With Three Strange Loves (originally titled Thirst) and later discoveries like The Devil’s Wanton, I realized the “melancholy Swede” had created some very lurid mellers in his early years (no problem there), and these needed investigation. 17 films later, the fruit of these viewings is contained in this tribute to the early Ingmar, containing clips from 10 of the films. In the process, you will see the Master come of age as he wends his way through a most subversive bunch of “problem dramas” and gorgeously existential, doomed romances between extremely photogenic young folk. The most interesting thing to me about my journey through these films was revisiting the now reviled but still extremely indispensable medium of VHS: six of the 10 films included here aren’t available on disc, and the VHS copies range from classic 16mm transfers (with the occasional white-on-white images — if you’re a seasoned vet of the rep house, you’ll be able to still read the sentences with “missing” words), to early so-so VHS releases, to the very well-done tapes with yellow subtitles (a masterly invention that is now frowned upon as being intrusive — but not half as ridiculous as white-on-white sequences on DVD in the 21st century!). On the journey you’ll see some of the scenes that brought the attention of American exploitation distributors to Bergman before he got international acclaim with Smiles of a Summer Night (his women were some of the most beautiful in European cinema and, yes, he dated pretty much all of them), and will learn which of his films are the favorites of Godard, Rivette, and John Waters.

735.) In 2007 I was very glad to conduct three “update” interviews with individuals we had spoken to before on the program. Viewers have already seen my lengthier chats with Guy Maddin and Hal Hartley, but I decided to delay showing my latest interview with Fassbinder editor, confidante, and legacy-keeper Juliane Lorenz until the Criterion Collection issued one of her key triumphs as the head of the Fassbinder Foundation, the restored Berlin Alexanderplatz. We spoke upon the U.S. premiere of the film at MOMA, and in this first part of our interview she offers information about the restoration process as well as the far thornier financial aspect of the process. In the process we show short clips from the film, as well as bits from the Criterion release’s extras, which include two documentaries made by Ms. Lorenz and a vintage behind-the-scenes program that aired on German TV back in 1980. Among the topics we cover are the music rights for the mind-blowing epilogue to the film (in which our antihero’s wild fantasies and fears are punctuated by Fassbinder’s fave pop and rock tunes); the fact that this epic masterwork and Fassbinder’s later features were comprised mostly of “one take” sequences; and, for the hardcore among us, a few of the super-rare Fassbinder titles that Ms. Lorenz has acquired or has been blocked from releasing.

736.) Christmastime means variety specials to me, and so this Yuletide I had to share a new acquisition, the Dean Martin Show Xmas special from 1967. The show is an archetypal “family” special with Dino bringing on his entire brood, including his second wife Jeanne. This is a dual family show, though, and so Dean also welcomes a close friend and his three grown kids, Frank Sinatra and Nancy, Frank Jr., and Tina. The fact that the Martin and Sinatra clans are not particularly tuneful as a whole doesn’t detract from this show’s entertainment value, in fact it increases it. The show opens with an infectiously goofy duet between Dean and Frank that I just can’t get outta my head (best known by Darlene Love, but it was first sung by their role model, Bing Crosby). After that, a series of typically coy two-handers between their progeny, and then we get what we’ve been waitin’ for: some gorgeous examples of what the boys did so well in a final “living room” get-together and an energetic two-man song marathon that has become legendary for its camaraderie and sheer enthusiasm (and this from the ever-so-tame-on-TV Frank!). Variety specials were the truest cornucopias of the holiday season, and I’m proud to share some commentary about, and sequences from, this item, which turns 40 this year.

737.) As 1950s TV has all but disappeared from the rerun cycles of the “classic TV” networks (let’s all name in unison the only three that survive: Lucy, Honeymooners, Twilight Zone), I am always thrilled to be able to talk about a show from that era on the Funhouse. This week it’s a celebration of the first DVD box set of Mr. Peepers, the utterly charming, seriously low-key sitcom (1952-55) about a milquetoasty junior-high teacher. The lead is played by Funhouse fave Wally Cox, the man who gave us “Dufo: What a Crazy Guy” and, yes, the voice of Underdog. The box offers the first few months of the program, and thus we’re able to see early TV at its best: staging for the camera, flubbed lines that are “saved” at the last minute, and techniques that were dragged over from radio (including an off-camera “vocal effects” engineer). The program itself is an amiable bit of light comedy with nicely sketched characters: Peepers himself, his erstwhile girlfriend the school nurse, the sputtering older teacher (Marion Lorne, later of Bewitched), and Peepers’ bachelor-on-the-prowl buddy (played by a young and seriously energetic Tony Randall). Peepers may not have provoke the belly laughs that can be found in Sid Caesar’s work from the early years of “vaudeo,” but it truly is a gem in its own right. And I’m glad not to once mention in the episode Wally’s wildly famous NYC roommate, a certain guy named Brando.

738.) This week I present a vintage episode, featuring my interview with filmmaker Laurent Cantet. His film Heading South is an alternately sad and sexy character study of a group of middle-aged (and older) white women who journey to Haiti in the early 1970s to partake of the young gentlemen who act as their consorts/gigolos for the duration of their stay. Charlotte Rampling is the uncommonly sexy 55-year-old “Queen Bee” of the establishment (she’s 60 in real life, and looking very fine indeed for a senior citizen); underrated actress Karen Young is a Southerner who believes she’s found true love with one of the young Haitian men. Monsieur Cantet concocts a story of May-December longing that’s worthy of Tennessee Williams and Fassbinder (hear his true inspiration in the interview), that is distinguished by uniformly excellent performances and very fine scripting – one senses that, like Francois Ozon, he is a literarily-minded filmmaker who devotes very much time to the crafting of his characters and their dialogue. We discuss South, but also delve back into his preceding film, Time Out, which is a haunting character study of a man who spends his days deceiving his family into thinking he has a prominent job as an executive when he is actually drifting around the countryside, procuring money through a series of schemes. For those keeping score of this storyline and its discussion on the Funhouse, we have now spoken to three individuals about this very singular plot twist and its use in two French films from 2001-2002: Emmanuelle Carrere, who wrote a semi-fictional account of the real-life gentleman who almost carried off this scam (but brutally killed his wife and kids when he was found out); Nicole Garcia, who made the film L’Adversaire from Carrere’s book; and now Cantet, who took the factual tale, stripped out the murder aspect, and contrived a brilliant meditation on the alienation and fear that accompanies the loss of employment (plus one of the only films to weave the cellphone into its plotline in an absolutely essential way). We are undoubtedly the only program in North America to discuss this very original plotline – and I’m still wondering why it hasn’t been stolen and retrofitted for a bad Hollywood remake starring one of those dimwitted babyfaced actors that Scorsese casts these days.

739.) The era of the literary celebrity is long past, and certainly the recent death of the oldest enfant terrible in the biz, Norman Mailer, helped to seal it off for good. Mailer was a titan of American letters, and also mass-media provocation. An eloquent, thoughtful, positively brilliant guy, he could also be a cantankerous, angry, pompous wild man. One word that always was appropriate was “unpredictable,” and so I offer up an episode (part one of two) devoted to the many sides of the Norm. I start off with some reflections on Mailer’s media personality, and an “inspirational reading” from his book of poetry (yes, he wrote poetry). We then move on to clips of Mailer the provocateur in the public arena, protesting the Vietnam war, debating feminists at NYC’s Town Hall, and showing up unexpectedly in arthouse films. The feature pic of the evening, of course, has to be his masterfully bizarro noir comedy/melodrama creation, Tough Guys Don’t Dance. You will find out how Isabella Rossellini could “dig Big Stupe”….

740.) One extremely gratifying thing about doing the Funhouse for so many years is that some of the films I’ve spoken about in hallowed tones eventually show up on the “mail order” circuit. Such is the case with the feature presentation in this week’s second and final part of my Deceased Artiste tribute to literary wildman Norman Mailer, Maidstone (1971). We start out first, though, with brief clips from Norman’s first foray into experimental cinema, Wild 90 (1967), a film that attempts to marry Shirley Clarke’s The Connection, Warhol’s cramped-quarters ad-lib experiments, and Norman’s perception of the everyday New York gangster (which is somewhere to the cartoony left of Damon Runyon’s masterful creations, minus the wit and innovative slanguage). You will see a drunk Norman bark at a dog (and make it rear back slightly), exchange bon mots with his equally furtive actor pals, and generally just play the boiled ham. Then we move onto the Man’s ultimate statement about the traumatic events of 1968, Maidstone. Conceived as part party-game and part experimental film, it is a collection of excesses and moments of sheer crazed genius, punctuated by long stretches of, well… not much of anything. I have sliced away the last-mentioned and provide viewers with a few of the key sequences, including a blissful “seduction scene” featuring Norman, and the immortal moment where Rip Torn attacked him with a hammer for narrative purposes and ended up having part of his ear bitten off. The fight itself is up on YouTube, but the helpful posters have never provided the really long and heated post-fight discussion the men proceeded to have about assaination, filmmaking, and which one of them is the “champ of shit.” You can’t possibly manufacture stuff like this, it is pure Sixties.

741.) As I often say on the show, I never get tired of certain artists’ work, and one of those people is the late, very great Serge Gainsbourg. So this week I share my latest acquisition concerning Monsieur Gainsbarre, a DVD collection from France that for the first time offers English subtitles for the interviews with Serge that were conducted from the mid-’60s to the early ’80s. He went through a number of changes in his career, and while his music is the single best barometer of where he stood emotionally and intellectually at any given time, the interviews he gave on French television were truly eye-openers. His different faces are here: from an extremely nervous jazz vocalist who was experimenting with African rhythms, to the confident crafter of pop-rock and yé-yé singles, to the master musician creating theme albums that continue to be extremely influential, to the somewhat depressed and haggard older Serge who longs for the pure art of the past. I included some gorgeous and memorably hook-y musical interludes to punctuate this portrait of the brilliant and willfully sleazy genius who was Gainsbourg.

742.) The second and final part of my recent interview with Fassbinder Foundation head Juliane Lorenz starts out in a fanboy fever, as I try to untangle the web of DVD labels on which Fassbinder’s films have been released in America over the past few years. Ms. Lorenz responds with her own level of confusion — it’s interesting to note that the one release I mention that she was completely unaware of contains as its central supplement… an interview with Juliane Lorenz! We turn from the DVDs to the films themselves, discussing Fassbinder’s feeling for his characters, and then talk about Fassbinder’s presence on German TV. Included are clips from the latest DVD releases, including the titanic Criterion box set of RWF’s masterwork Berlin Alexanderplatz.

743.) Vintage episode: One of the greatest delights of my teenage years as a filmgoer was discovering films that virtually cried out to be reseen; such were the joys of the 1970s work of John Waters, whose brilliantly acidic dialogue was delivered with insane gusto by his “Dreamland” players. I’m proud this week to be speaking to one of the foremost practitioners of his very special brand of sarcasm, the lovely and talented Mink Stole. We spoke to Mink at a recent Chiller Theatre convention, and got the lowdown on her seminal work for Waters, from one of the initial super-8 productions to the 16mm cult classics to scene-stealing supporting parts in the more viewer-friendly, bigger-budgeted productions of the post-Divine era. Topics we explore with Ms. Stole include her “exit interview” from the Catholic church (an excuse should never be needed to show the exquisitely blasphemous “rosary job” from Waters’ first perfectly-formed act of provocation, Multiple Maniacs); her special talent for delivering Waters’ most witheringly sarcastic lines of dialogue; and her peculiar sex appeal, which may appear outré to most (including Ms. Stole herself), but was readily apparent to the teenage version of yours truly. Included are my choices for the best bits of her work for Waters (catch the odd glimpse at the camera in the dialogue scene with Divine in Maniacs) and information on her latter-day career as a singer and cameo-role specialist.

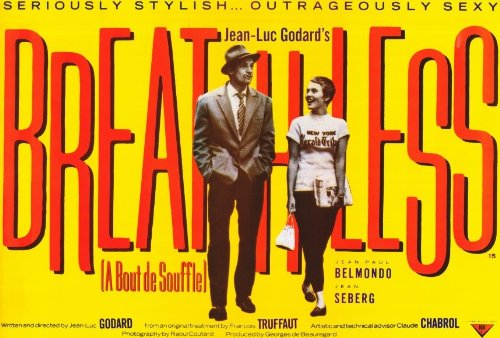

744.) The French New Wave still have an immense amount to teach us, and this week in the Funhouse we look at the work of two of the group’s purest cineastes. First up is a review of Jacques Rivette’s latest film The Duchess of Langeais, a period love story by Balzac that concerns the tormented relationship of a general and a socialite. From Rivette’s newest creation we move to one of Godard’s finest, Pierrot Le Fou, which has finally gotten the “Criterion treatment” with a restored print and a trove of extras. After discussing one of Uncle Jean’s finest, we close with a new 3-disc collection of his later features, that happens to include two unadulterated masterpieces, Passion and First Name Carmen (the first film where he assumed his crazy “Uncle Jean” persona). I discuss some of the hallmarks of the JLG style, while sampling some brilliant short clips — the bar don’t go no higher.

745.) A face you will recognize, a name you may not, that’s Gerrit Graham, our guest this week in the Funhouse. Part 1 of my interview with this character actor extraordinaire focuses exclusively on his work with Brian De Palma (in his still-exciting “young turk” phase). We start out with a discussion of Gerrit’s improv work at the Second City during the end of the ’60s, which served him well when De Palma’s earliest films called for the cast actors to “vamp” their dialogue based on a few chosen premises. The results can be seen in Greetings (1968), a flashily-edited bit of NYC ’60s brilliance that finds Robert De Niro, Graham, and Jonathan Warden attempting to avoid the draft, find chicks, and expose the Warren Commission all in the space of a few days. The group reconvened in the sequel Hi Mom! (1970), in which Gerrit plays a white radical who takes part in a interactive theater piece called “Be Black, Baby” — an experience that he describes in our interview as being unpredictable, to say the least. We close out part one talking about his memorably over-the-top comic turn as “Beef” in one of our fave Funhouse cult pics, The Phantom of the Paradise (1974), one of the finest comic book/horror/musical/comedies ever made.

746.) Light and shadow. Drama and comedy. Music and silence. This week in the Funhouse Consumer Guide dept I’m reviewing releases from Kino Video that feed into my auteurist fascinations while still offering a solid dose of entertainment value. First we journey back to the world of Germany “between the wars” with the newest, spiffiest restoration of Nosferatu, which has been released with a bonus documentary that details the occult side of the production. Next up is the German Expressionist Collection, a set of four titles that includes the landmark Hands of Orlac (Conrad Veidt, Expressionist Man extraordinaire!) and Pabst’s Freud-can-set-you-free Secrets of a Soul. The final segment concerns four 1980s films by Alain Resnais that have finally found a home on U.S. video shelves. The quartet ranges from the radically strange genre-bender Life is a Bed of Roses (1983) to the not-always-successful-but-damned-fascinating I Want to Go Home, in which Resnais pays tribute to his American cartoon and comic-book heroes with a lopsided farce scripted by Jules Feiffer.

747.) Part two of my interview with character actor extraordinaire Gerrit Graham picks up on our discussion of The Phantom of the Paradise, this time covering the Phan-dom that has been devoted to this terrific 1974 cult movie. We next discuss another rambunctious comedy, Home Movies, an underseen farce about student moviemaking that was probably the last great “unstructured” (and endlessly entertaining) film by Brian De Palma. We leave De Palma behind to talk about cult comedy Used Cars, a pre-gimmick Robert Zemeckis bad-taste comedy that features Gerrit in a showy role as Kurt Russell’s superstitious friend. We lastly touch on the immense amount of TV work he’s done by focusing in on his two appearances on latter day Star Trek series, and his take on the cult-audience phenomenon, for Phantom, Trek, and the very busy Chiller Theatre con he was guesting at.

748.) The second of what I hope will be an ongoing series about 1950s comedy TV series, this week’s episode salutes the great The Phil Silvers Show, aka You’ll Never Get Rich (best known as “Sgt. Bilko”). Bilko was a brilliantly written, four-season (1955-59) sitcom that spotlighted the talents of the late, great Phil Silvers as a top-notch con man, card sharp, wise-ass, and shameless sycophant — who just happened to be a Sergeant in the army. Nat Hiken’s wonderfully structured scripts made the show as memorable as it was, and the casting was sublime. My own exploration of the program, drawing on the sole DVD box set of the series, goes into the Sarge’s scams, his always unsuccessful cover-ups, and the show’s terrific support cast, which ranged from the regulars (including the cartoon-come-to-life Maurice Gosfield, as Doberman, and chief stooge and bottle-washers Harvey Lembeck and Allan Melvin) to performers who later became TV stars in their own right. “Bilko” has been proclaimed one of the best sitcoms ever by some of today’s top comics, including Larry David and Ricky Gervais, and I think even a small sampling of the show demonstrates why.

749.) Easter time is upon us once more, and so it’s the season for religious kitsch. This year I’m upping the ante, and instead of just mocking the (bountiful) kitsch spawned by Christianity, I’m aiming for a trifecta. First we’ll be seeing some lovely oil paintings of one of “the most popular writers of the 1930s” before he spawned a self-help philosophy that his followers (and the I.R.S.) deem a religion. Next we move on to the granddaddy of biblio-centric religions, Judaism, and sample a little bit of a children’s video series intended to teach kids how much fun it is to study the Torah — and, yes, since it is kid’s entertainment, there’s a guy hamming it up as a villain and some really cheesy humor. From that point on, it’s back to familiar territory, as I run through a panoply of crucifix and Christ-adorned crap for kids’ parties. And then we travel straight to hell—in a Nigerian shot-on-video cautionary tale (involving a devil baby and demonic gay men!), and as interpreted by the late, great Ron Ormond in his masterfully creepy and over-the-top Estus Pirkle epic The Burning Hell (1974).

750.) At some point in the future folks are going to look back at the films and videos of Chris Marker, and realize that this “anonymous” essayist was perhaps one of the greatest artists (and greatest minds) of the latter half of the 20th century. This week I’m proud to comment on two of his little-seen works — in fact, pretty much all of his filmography is little-seen outside of the two works that have constantly been in circulation (La Jetee, Sans Soleil). Marker’s favorite topics are memory, the image, the media and, of course, cats. He also has made some of the most brilliant political features and shorts; among them is The Sixth Side of the Pentagon, his account of the 1967 March on the Pentagon. Marker was in the thick of things with his portable camera, and caught the event from “inside.” Nearly four decades later he made another feature about youth participating in what the French call “demos,” The Case of the Grinning Cat. The latter is a richly textured essay about political dissent in the 21st century, the power of graffiti (or as Mailer called it, “the faith of graffiti”) and, again, cats. Marker’s works grow richer with each reviewing, and are vastly underrated and under-shown. One wonders at what point his works will “emerge” from their current position in U.S. distribution limbo.

751.) Variety is the spice of life, and also the Funhouse… Thus, tonight’s Consumer Guide offers a look back at TV in the ’70s through the vehicle of three variety shows hosted by guy-girl musical acts and now available in TV-on-DVD box-sets. The first is the seminal Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour, the program that featured the “hippie” duo in their Vegas-refined guise as a wacky, unpredictable short Italian and his statuesque, glamorous straight-woman wife (think Louis Prima and Keely Smith — but joking about sex). The most interesting thing about S&C’s TV odyssey as a duo? The fact that their variety show came back after they were divorced, truly a one-off in television history. The guests excerpted range from Howard Cosell (singing doo-wop) and young Michael Jackson (serenading his rat-friend Ben) to future variety show hosts Donny and Marie. Next up is The Captain and Tennille Show which surely took a leaf or two from S&C’s book, but this couple really did have affection for each other (and in fact are still married to this day). The show itself benefited from the convergence of “old” and “new” that we love to explore in the world of ’60s and ’70s variety shows — meaning that Hope, Gleason, and Burns could be seen alongside the latest pop stars, nearly all of ABC’s then-hot stars (from the Sweathogs to the Happy Days gang and Charlie’s Angels) and Leonard Nimoy (reciting his I Am Not Spock-era poetry). The last show reviewed is the one that I remember with a surprising and nearly scary amount of crystal-clarity: The Tony Orlando and Dawn Show. The single best host of the NYC end of the Jerry Lewis MDA telethon was a startlingly energetic performer back in the Seventies who modeled some very kitschy fashion on the show (on purpose, to rouse wisecracks from his fellow singers, Telma Hopkins and Joyce Vincent Wilson) and got to interact with a sublime roster of Funhouse favorites, from Freddie Prinze (Sr., man, Sr.!) and Jerry Lewis to Alice Cooper.

752.) The items reviewed in the Consumer Guide dept. of the Funhouse sometimes have something in common, sometimes they don’t. This week I tackle two releases from the company Shout! Factory that have nothing specific in common, except that when taken together we are able to worship, yet again, the heroes Marx and Lennon. The latter is seen in his last TV interview on the boorish but always compulsively watchable Tom Snyder’s Tomorrow Show; this historic broadcast has been put on DVD by Shout! along with two other solo Beatle chats conducted by chucklin’, smokin’ Tom. Next, we move onto two slightly older releases from the company, items I didn’t want to review or use excerpts from until I’d watched them in their entirety (that’s the way the Funhouse swings). And thus, now that all has been consumed, I can continue our informal survey of 1950s TV comedy by spotlighting the two Shout! collections of You Bet Your Life. Included are episodes that haven’t aired since the early ’50s, vintage commercials, post-YBYL Groucho pilots, and wonderful “stag reels” of material cut from the episodes. Also present are some one-of-a-kind guests including spoken-word god Lord Buckley and TV genius (and Groucho’s cigar pal) Ernie Kovacs.

753.) Vintage ep: I value the notion of continuity in the Funhouse, and so I’m always glad to be able to continue an ongoing discussion about a filmmaker’s work. We do exactly that this week with Hal Hartley, whom I first interviewed on the program about his film Henry Fool back in 1997; now, ten years later, we discuss the release of his sequel to that film, Fay Grim. We were able to cover a lot of ground with Hal, so much so that our interview will run to two episodes. Here we start out talking about the “day and date” release of Fay, meaning that the film was released to theatres right before — in this case less than a week before — its DVD street date. We then discuss the Hartley features “missing” on DVD (including arguably his finest, Trust) and the way that Fay utilizes one of the finest elements of his work, his quick, deadpan dialogue. We close this installment of the interview with a discussion of the three movies that preceded Fay, which stood the sci-fi/fairy tale/religious allegory genres on their respective heads.

754.) It’s always a pleasure to have an extended chat with a fave filmmaker on the program; thus, this week’s part two of my interview with Hal Hartley finds him discussing his older work, as well as his influences. We start out with my asking him about the influence of Feuillade on his latest spy satire Fay Grim. From that initial query, we move to the French’s love/hate relationship with his work (the critics don’t favor him anymore, but he is a Chevalier of Arts and Letters!). From there, we discuss his work with one of the finest French actresses around, Isabelle Huppert. Which leads to a discussion about independent filmmakers owning their works outright, and a reflection on his heroes as a filmmaker (supplemented by my own “mega-mix” of Hartley/Godard clips!). We close out with a sideways mention by yrs truly of a filmmaker who turns out to be the one who made the film (and a specific scene in particular) which Hal notes he’s “ripped off” many times, as he honed his own uniquely terse and funny style of dialogue.

755.) Vintage ep: Every time someone talks about TV being so bold in the 21st century, I think back to the much-maligned (and thoroughly confused) 1970s, and remember when network television actually broke boundaries by throwing previously held notions of taste straight out the window. A good example of this idea was The Dean Martin Show, a variety series that exulted in being slick but haphazard, with the charming presence of Dino carrying the day no matter how dismal the sketch, how weary the song, and how perfunctory the guest-star patter. Dean’s show became outdated by the early ’70s and so the producers hit on the notion of doing TV-friendly “roasts” of celebrities, a la the Friars. The results were pre-packaged hours of insult comedy, that ran the gamut from the totally innocuous (I mean how much can you really insult Jimmy Stewart, anyway?) to the ludicrous (“Man of the Hour” honorees included Evel Knievel, Mr. T, Gabe Kaplan, Ralph Nader, Dan Haggerty, and…George Washington?). Tonight, we’ll take a look back at the Dean Martin roasts, for what is surely the first of several visits into the video archive. The focus, since it’s the most striking element in the shows, is on the insanely racist jokes that were slung at African-American “Men of the Hour,” as well as the standard bits (yes, we’ve got Red Buttons, no, there’ll be no Foster Brooks). We present an overview of the roasts through some of the oldest, saddest, and snottiest, jokes you’ve ever heard. We work our way toward an amazing timepiece, the roast of our favorite all-around entertainer, Sammy Davis Jr., but in the process, you’ll see a number of deceased artistes, who kicked off since we originally shot the host segments, including Frank Gorshin (only present when there’s no Rich Little), Eddie Albert, and roast perennial Nipsey Russell. It was very a different time, and a very, very different form of entertainment – but it’s a hell of a lot more endearing than the present-day procession of stand-ups that makes up the current Comedy Central TV roasts.

756.) Vintage episode: I try to be nothing if not thorough on the show, so this week it’s part two of my Deceased Artiste tribute to the inimitable Robert Altman. This time out, three segments present the lesser-seen side of this incredible filmmaker, with a choice selection of clips (only one of which has ever been featured before on the show). The first topic are the “dream films” Altman made in the ’70s, the purest expressions of his sensibility, three films that have nothing whatsoever to do with the large-ensemble pieces for which he was best known. Next I discuss his “theatrical period,” the post-Popeye era in which he created a series of tightly constructed films that did strictly adhere to their scripts and contained the most impressive camerawork outside of European auteurist fare. Last, I counterpoint the only two non-“theatrical” films he made in the 1980s, O.C. & Stiggs and Vincent & Theo. One is a deceptively lackadaisical attack on suburbia and the John Hughes-era teen pic (which Altman detested); the other one of the best portraits of a visual artist in torment. Despite its spinning down into entropy, I highly prize O.C. (although he claimed to hate the script, his attitude melds perfectly with the National Lampoon source material, and what a cast of Funhouse favorites!), and think Vincent proved once and for all — as if proving was needed after the masterful Streamers, Secret Honor, and the other theatrical films — that Altman was not a one-trick pony, and could have, at any point, relocated permanently to Europe and made perfectly brilliant films over there.

757.) Vintage: The past few films by Guy Maddin have all been considered “events” by his fans, but his latest, Brand Upon the Brain!, truly became an event upon its release: it was shown with live accompaniment by a mini-orchestra, five Foley artists, and a “castrato” singer. The coup de grace was a celebrity narrator (the roster in NYC included poet John Ashbery, Lou Reed, Crispen Glover, Eli Wallach, and Isabella Rossellini), who took a crack at reading the highly melodramatic v.o. that Maddin’s “muse” Louis Negin concocted for the film. In this episode, I speak to Guy about the week-long run of the “live” version of the film, discussing his jittery feelings about the production and his surprise at the different spins his material was given by the celeb narrators. We also talk about the themes that have linked his work thus far, including a wildly Freudian view of the nuclear family, a polymorphous perversity that won’t quit, and humor that ranges from deadpan faux melodrama to raucous Three Stooges-style bonks-in-the-head.

758.) This week it’s part two of my interview with visualist and filmmaker-in-transition Guy Maddin, upon the NYC live-event screenings of his film Brand Upon the Brain! In this section of the interview, we discuss Brand…! at length, starting off with another question about Maddin’s visual style, which is as complex — yet easy to “receive” — as his latter-day, “underground” style of editing. We talk about the Maddin family secrets, which aren’t secrets anymore, but “clues” in the melodramatic storylines that accompany his black-and-white and monochrome fantasies, and also address the presence of a masked, tuxedo and top hat-clad detective in his film, a teen lesbian variant on the glorious “Fantomas” master-thief character, a staple in French literature and cinema that we’ve discussed on the program before. We close out with a discussion of Isabella Rossellini, with whom Guy has now worked three times, and somehow work our way around to mentions of both Mickey Rooney and the revered Dick Shawn, which is always as good place as any to close off an interview with an unique and fascinating filmmaker.

759.) Unique juxtapositions are our stock-in-trade in the Funhouse, and this week’s Consumer Guide offers up yet another combination platter of auteurist discussion. The first segment focuses on the recent release of a trilogy of later work by cult genre director Seijun Suzuki. The films are all willfully strange, and contain imagery and surreal bursts of imagination that have influenced our favorites Wong Kar-Wai and “Beat” Takeshi. They’re not an easy journey to make, but they establish Suzuki as a quite singular artist who, like Bunuel, has fans who only dig his earlier subvert-the-genre work and others who prefer him when he shed the action-movie trappings and moved full-tilt into “arthouse” mode. The second feature of the evening is an interview I conducted recently with Steve Buscemi upon the opening of his film Lonesome Jim. We discuss the film’s bleak (and very funny) brand of humor, as well his use of a Panasonic mini-DV camera to shoot the picture (the very same camera that spawns the Funhouse these days). Most interesting are his comments about the work of John Cassavetes and yet another Funhouse fave, the Finnish master of the deadpan comedy of despair, Aki Kaurismaki.

760.) At the intersection of stand-up comedy, performance art, and sheer insanity exists the professional wrestling phenomenon known as “mic work.” These days it is nearly a lost art — with the exception of the occasional outburst from an old pro like Ric Flair or a modern master of hardcore lunacy like Mick Foley — but in the golden days of the 1960s-80s, giants ruled the arenas, and ranted like nobody’s business on microphones snatched out of announcers’ hands. Such a man was the great Captain Louis Albano, who is our interview subject this week in the Funhouse. The Captain was a man who did it all in the business of what is now called “sports entertainment”: he wrestled, did interviews, participated in stunts, wore eye-offending duds, broke the rules, and managed eighteen tag teams to the championship belt. We conducted our talk with the big man (now a good degree svelter) at the end of a long day at the Chiller Theatre convention, so yours truly was tired, but woken up immediately by the energy of this 73-year-old former “champeen.” (Rarely would I ever leave a moment in which a security guard comes in a room to see when an interview will be finished, but the Captain’s command of the situation deserves an airing.) We discuss his career inside “the squared circle” and his subsequent show biz career, from his 1960s tenure in a mock-Mafia tag team called “The Sicilians” (not appreciated by the boys with the bent noses) to his “breakthrough” feuding with fan and friend Cyndi Lauper to his acting in Brian De Palma’s Wise Guys and the starring role in the extremely ’80s kids’ program The Super Mario Bros. Super Show (no matter how hard I try I am not gonna ever get the closing song, “Do The Mario,” outta my head). It is a testament to the Cap that, although he is prone to tall tales and just a few exaggerations, one of the fully accurate things he mentions is his having raised millions of dollars with Cyndi for victims of multiple sclerosis. They don’t make ’em like Lou anymore, and I was quite pleased to wind him up and let him go…

761.) Vintage: When yours truly turns “another year older and deeper in debt,” it’s time to salute an Artiste whose work I’ve admired who hasn’t hit the great divide. This time out – after a short editorial reflection on the “branding” of American pop culture – it’s time to pay tribute to the great Martin Mull, a gent whose wry, deadpan, slightly surreal humor has been largely overlooked in discussions of the finer points of ’70s pop culture. The focus is on his best showcase, the Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman spinoff Fernwood 2-Night (and its later incarnation America 2-Night). Fernwood is right up there in the pantheon of talkshow satires (with SCTV’s “Sammy Maudlin” skits, The Larry Sanders Show, and the BBC “Alan Partridge” cycle), and is even more astonishing these days as a gorgeous example of the politically incorrect, and exceptionally funny, humor that flourished in the ’70s. Also included are clips of Mull at his best, onstage with his “Fabulous Furniture,” crooning hooky little numbers that mocked the “tragically hip” sensibility (while saluting: midgets, eggs, fetishes, noses, onanism, Jesus, and the “Cleveland blues”), and burned their way into the brain of your humble host during his childhood and teen years.

762.) Vintage ep: The music of the ’60s haunts us still – and it ain’t just that classic rock and endlessly recycled and promoted cache of oldies. Tonight’s Consumer Guide is a quite informal survey of the period’s pop, starting out with a tribute to the recent DVD release of The Bugaloos, the Kroft show that featured British performers dressed as bugs giving us bubblegum joy, courtesy of the mighty Charles Fox, while evading villainous Benita Bizarre (Martha Raye). The songs are as catchy as hell, and although I had misplaced my memories of the program from childhood, a viewing in the mid-90s reopened the floodgates, as well as a devotion to gal Bugaloo Caroline Ellis. I follow that with a further discussion of the Scopitone phenomenon, this time focusing on the items being made available on the www.bedazzled.tv that run the gamut from further French items I never knew existed (Jacques Brel in the film-jukebox?) to very obscure American items. Included are what must be the first parody of Gainsbourg (a spoof of “Je T’Aime, Moi Non Plus”), an ode to sado-masochism, and a severely whitebread folk tune that includes the refrain “wackadoo, wackadoo, wackadoo.” There’s no way to follow that kind of sincere kitsch but with the master of all things dazzling in the Sixties, Russ Meyer. I review the recent DVD release of Russ’s big-studio bow, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, and offer reflection on the missing elements (Ebert strategically avoids an in-depth discussion of the Manson aspect of the pic, even though he’s doing an audio commentary for the freaking thing) and the bonus gems (rare trailers that show Russ at work on a BVD photo session and offer his lightning-fast editing, with a narration that is indisputably his work). Russ has been gone for a few years now, but the hypnotic relentlessness of his montage continues to amaze….

763.) Vintage ep: We close out our tribute to Deceased Artiste Sir Peter Ustinov with part two of my interview with the gent and several clips illustrating the breadth of his film work. We start out with a discussion of his finest film as a director, Billy Budd, and then swiftly turn to the character he was best known for in the latter part of his career, Belgian (not French, please no) super-sleuth and primpin’ dandy Hercule Poirot. My chat with the great man includes his discussion of the similarities between the legendary Max Ophuls and his confessed number one fan, Stanley Kubrick. In the process we talk about Ophuls’ never-realized project to follow Lola Montez and Ustinov’s wonderful English-language narration for Le Plaisir; this last is a particularly wonderful bit of business that finds Sir Peter impersonating Guy de Maupassant, speaking from beyond the grave. Some further reflections on Spartacus and Stanley K. lead to the finish, at which point I slid in the question that one is tempted to ask all older artists (that nasty little bit about “proudest achievement”). All in all, a Funhouse episode for the time capsule (to borrow Joe Franklin’s fave phrase), one that I’d include in the top ten of the few hundred we’ve done during the past 11 years hangin’ around your TV dial.

764.) This week’s vintage episode features part four of my talk with D.A. Pennebaker and his collaborator-wife Chris Hegedus. This program features an informal survey of his concert films. We discuss his work with Ms. Hegedus on Depeche Mode 101, a concert movie that shows the band at their syntho-pop finest (pre-heroin, so no fun backstage hijinks). The movie also follows an obnoxious group of their fans (contest winners) who travel around seeing the band’s gigs in several states-herein lies the true moment where a master of cinema verite unwittingly prefigured the “reality show,” since this bunch of cosmeticized, teased-hair fanboys and girls are the very prototype of the casts of “The Real World,” “Big Brother,” and every other serialized horror currently airing. We also discuss the 1969 Toronto Rock ‘n’ Roll Revival, where Pennebaker and company shot the first generation of rockers, as well as John Lennon and an impromptu Plastic Ono Band, among others. Most indispensable: Pennebaker’s meditations on his collaboration with Richard Leacock and our hero, Jean-Luc Godard, on the very odd One A.M. See the Jefferson Airplane perform on an urban rooftop well before the Beatles, watch Eldridge Cleaver get snotty to Uncle Jean, and, most importantly, see Rip Torn roam through an NYC construction site quoting a Black Panther speech at the top of his lungs.

765.) In 2007 I was very glad to conduct three “update” interviews with individuals we had spoken to before on the program. Viewers have already seen my lengthier chats with Guy Maddin and Hal Hartley, but I decided to delay showing my latest interview with Fassbinder editor, confidante, and legacy-keeper Juliane Lorenz until the Criterion Collection issued one of her key triumphs as the head of the Fassbinder Foundation, the restored Berlin Alexanderplatz. We spoke upon the U.S. premiere of the film at MOMA, and in this first part of our interview she offers information about the restoration process as well as the far thornier financial aspect of the process. In the process we show short clips from the film, as well as bits from the Criterion release’s extras, which include two documentaries made by Ms. Lorenz and a vintage behind-the-scenes program that aired on German TV back in 1980. Among the topics we cover are the music rights for the mind-blowing epilogue to the film (in which our antihero’s wild fantasies and fears are punctuated by Fassbinder’s fave pop and rock tunes); the fact that this epic masterwork and Fassbinder’s later features were comprised mostly of “one take” sequences; and, for the hardcore among us, a few of the super-rare Fassbinder titles that Ms. Lorenz has acquired or has been blocked from releasing.

766.) The second and final part of my recent interview with Fassbinder Foundation head Juliane Lorenz starts out in a fanboy fever, as I try to untangle the web of DVD labels on which Fassbinder’s films have been released in America over the past few years. Ms. Lorenz responds with her own level of confusion — it’s interesting to note that the one release I mention that she was completely unaware of contains as its central supplement… an interview with Juliane Lorenz! We turn from the DVDs to the films themselves, discussing Fassbinder’s feeling for his characters, and then talk about Fassbinder’s presence on German TV. Included are clips from the latest DVD releases, including the titanic Criterion box set of RWF’s masterwork Berlin Alexanderplatz.

767.) Certain American filmmakers are better known in Europe than they are here in the States, and one of them is Jerry Schatzberg, who made a trio of utterly superb movies during the heyday of the “maverick” movement in Hollywood and has continued to work as both a successful photographer and filmmaker in the decades since. Some of his still images are iconic portraits of the Sixties (check them out at his website, www.jerryschatzberg.com), but my interview with the gentleman focuses primarily on his filmmaking. The first part of our talk spotlights his first two features, Puzzle of a Downfall Child, a study of a “past her prime” fashion model reflecting on her past (played to perfection by a young Faye Dunaway) and the seminal New York picture The Panic in Needle Park (1971), which gave Al Pacino his first starring movie role. Mr. Schatzberg offers an insight into what it was like making stark, uncompromising dramas during that seminal time in American film, and supplies background information on both movies, with reflections on Anne Saint Marie (the real-life inspiration for Puzzle), Dunaway, Pacino, Panic costar Kitty Winn (who won the Best Actress at Cannes that year), and his screenwriters, Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, and the “maverick” scripter Carol Eastman (who wrote Five Easy Pieces right after Puzzle).

768.) Part two of my interview with filmmaker Jerry Schatzberg picks up right where we left off: in the fascinating “maverick” period of early ’70s cinema, when the major studios were funding personal, adult movies that withstand repeating viewings and definitely qualify as the best American cinema has to offer. Such is the case with Scarecrow (1973), Mr. Schatzberg’s road movie with Gene Hackman and Al Pacino that has garnered a strong cult among filmmakers (most of them French) and novelists (one or two American). He offers reflections on the picture, discussing the acting methods of its star duo and the relative ease with which it was made, despite its being shot on location across the U.S. We move on to talk about a few of Mr. Schatzberg’s later films (he has worked frequently with stars on the rise, like Morgan Freeman in Street Smart, 1987), what Harold Pinter is like when he’s drunk, and Schatzberg’s preference for “downer” scenarios. We finish off by touching on his iconic ’60s photographs, from studies of Bob Dylan (including the Blonde on Blonde cover) to the Mothers and the Stones, and many of the ’60s most beautiful actresses.

769.) Think back to a time when American cinema was at its most original and unfettered, when the best filmmakers were making their most kinetic and intelligent work with major studio backing, and when the biggest young (and middle-aged) stars seemed to consistently make the right choices about what to appear in (whether or not it made money). Let’s stay in 1972 for a while, just long enough for an episode-long discussion about one of my favorite “small movies” of the early Seventies, Bob Rafelson’s King Of Marvin Gardens. The film has come out on DVD, but it has no “bonus supplements,” so I feel it necessary on the Funhouse to offer what could easily be a commentary track: the first part of my interview with the film’s screenwriter, Jacob Brackman, covers the genesis of the project, the time in which it was made, the strength of its casting, the fact that it pivots around an FM spoken-word deejay, and the choice of the then-dilapidated Atlantic City as its setting. The film is definitely one of the best Nixon-era statements about “the failure of the American Dream,” but it also is amusing, literate, and superbly acted. Oh, and thanks to Mr. Brackman, well-written.

770.) Part two of my interview with screenwriter Jacob Brackman, screenwriter of one of the finest “maverick” pictures of the early 1970s, Bob Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens. In this episode, we discuss Mr. Brackman’s friend Terrence Malick, whose gorgeously picturesque Days of Heaven (1978) he produced and worked on as a second-unit director. He reveals how he helped Malick shape the narrative, creating a montage-based picture out of a dialogue-heavy character study. We move from Malick’s sublime effort to a campier affair, 1980s Times Square, Mr. Brackman’s only other produced screenplay. Intended as Robert Stigwood’s “punk” companion piece to Saturday Night Fever, the picture is a strange time capsule of an era that never really was, shot on locations that were all too real and are now very sadly gone, most prominently “the Deuce.” We talk about the core of the pic, which is an implied lesbian relationship between two teenage girls, runaways living a wild (but curiously chaste life) right in Times Square. We then turn to Mr. Brackman’s other career, as a lyricist in the pop/rock/theater world, spotlighting his work in the early 1970s with Carly Simon, and close with, what else, the sublimely low-key King of Marvin Gardens, a true Funhouse favorite and a movie that deserves a bigger cult.

771.) Since the rerun networks (oh, excuse me, “classic TV”) show absolutely nothing in the way of variety shows — and very little in the way of anything pre 1980 — I feel it contingent upon the Funhouse to move back to the heyday of the format, the 1960s, when “old” met “new” and the guest-star rosters were just mind-blistering. This week’s episode salutes two very different sex symbols. The first is the very unlikely debauched genius Serge Gainsbourg, and the second is the Welsh wonderboy Tom “It’s Not Unusual” Jones. We have two featured segments, the first being scenes from an extremely rare 1966 French Jones special that happened to feature Serge as one of the musical guests. Tom spoke no French and communicates with only one guest (in English), but the guest-star roster of this music-only special is truly splendiferous: Serge, Francoise Hardy, an insanely gorgeous and melodically sound Marianne Faithfull, and two acts that once seen will not be easily forgotten (Eric Charden and ye-ye gal “Pussy Cat”). We move from TJ in the City of Lights to TJ in the UK, as I present of a review of, and a round-up of clips from, the new This is Tom Jones box set. The theme of the box is (taking a leaf from earlier Sullivan and Cavett collections) “Rock ’n’ Roll Legends,” but the truly important thing about the box is the way that it mingles some dated and not-so-dated comedy (Pat Paulsen, the Committee, the Ace Trucking Company, Richard Pryor) with a simply terrific assortment of musical guests (spotlighting Tom’s duets with Aretha, Joe Cocker, and Janis).

772.) As Labor Day approaches, it’s time once more for the annual Funhouse tribute to Jerry Lewis. Since I’ve explored his work for so many years on the program, this time I’ve decided to “dig deep” (as Jer encourages us to do every year on the telethon), and have come up with two of the more, let us say “demanding” projects Jerry was involved with. The first is the insanely awful movie that went to straight-to-video and remains the worst-ever adaptation of the wonderful work of Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Slapstick of Another Kind (different clips from the ones on the old Funhouse blog and YouTube). Each decade has its own brand of overwhelmingly misguided movie projects, and Slapstick truly belongs to the Reagan era. The cast is sublime (Jerry, Madeline Kahn, Marty Feldman, Jim Backus, Sam Fuller, Pat Morita) but the source material is uncertain and the approach is simply, well… you’ll see. We then provide viewers with a respite while some interesting footage of Jerry as testimonial speaker is shown, and then we move on to the feature of the evening, scenes from the landmark Jerry Lewis Show from 1963, the live primetime Saturday night project that still can stun 44 years down the line. It’s a variety show with few guests, and Jer is the center attraction — little more needs to be said.

773.) The death of one of the cinema’s great innovators deserved something a little different on the program, and so instead of launching into a biographical, chronological tribute to the late, great Ingmar Bergman in my first tribute episode, I decided to focus on the period of his work that has fascinated me the most, the 1960s. (The equally brilliant work from the breakthrough ’50s and the tortured-relationship ’70s will show up in the second episode.) This gave me the task of reliving this amazing group of “pictures” (Bergman’s own preferred English noun), and trying to put in perspective how this great artist responded to the social and cultural “rupture” that the Sixties represented. I start out with a discussion of the two trends in Bergman obituaries (wistful and downright wrong), and then head into the six-pack of films that remain as mind-warping today as when they first came out, starting with the 1963 fever dream The Silence and ending with the direct-address, things-fall-apart scenario The Passion of Anna (1969). Those who think of Bergman as a dryly literary or overly theatrical filmmaker might be thrown off, and hopefully mindfucked, by the bold modernity (and just plain strangeness) of these films. Included among them is the classic Persona, the blissfully out-there Hour of the Wolf (the single greatest statement on insomnia ever), and The Passion of Anna, spotlighted here by a Liv Ullmann monologue which Bergman cited in an interview as one of his favorite pieces of acting (for her part, Ullmann reveals on the DVD that a strategic edit he made in the film to another monologue bothers her to this day). Perhaps the oddest title is The Ritual (1969), a wonderfully warped TV film by Bergman about three performers under investigation by a judge/censor, who then voluntarily takes part in their bizarre stage ritual. God (or nothing), how I love this stuff.

774.) Though the Funhouse lasts a mere 28 minutes, the behind-the-scenes preparations for some episodes can take months in some instances. In the case of this week’s Deceased Artiste tribute to Ingmar Bergman (part two), I thought that, after the last 1960s-focused episode, I could move through the rest of his career in a single, second episode. Then I decided that, since I knew I really did like everything I’d seen of his but had hazy memories of even the most famous titles, I should take a look at a few of the 1950s classics — and then I did something I had sworn I wasn’t going to do. I took a chance on one of his earlier melodramas, a supposedly torrid group of pics that have been written off by most critics and pretty much dismissed by Bergman himself. With Three Strange Loves (originally titled Thirst) and later discoveries like The Devil’s Wanton, I realized the “melancholy Swede” had created some very lurid mellers in his early years (no problem there), and these needed investigation. 17 films later, the fruit of these viewings is contained in this tribute to the early Ingmar, containing clips from 10 of the films. In the process, you will see the Master come of age as he wends his way through a most subversive bunch of “problem dramas” and gorgeously existential, doomed romances between extremely photogenic young folk. The most interesting thing to me about my journey through these films was revisiting the now reviled but still extremely indispensable medium of VHS: six of the 10 films included here aren’t available on disc, and the VHS copies range from classic 16mm transfers (with the occasional white-on-white images — if you’re a seasoned vet of the rep house, you’ll be able to still read the sentences with “missing” words), to early so-so VHS releases, to the very well-done tapes with yellow subtitles (a masterly invention that is now frowned upon as being intrusive — but not half as ridiculous as white-on-white sequences on DVD in the 21st century!). On the journey you’ll see some of the scenes that brought the attention of American exploitation distributors to Bergman before he got international acclaim with Smiles of a Summer Night (his women were some of the most beautiful in European cinema and, yes, he dated pretty much all of them), and will learn which of his films are the favorites of Godard, Rivette, and John Waters.

775.) As 1950s TV has all but disappeared from the rerun cycles of the “classic TV” networks (let’s all name in unison the only three that survive: Lucy, Honeymooners, Twilight Zone), I am always thrilled to be able to talk about a show from that era on the Funhouse. This week it’s a celebration of the first DVD box set of Mr. Peepers, the utterly charming, seriously low-key sitcom (1952-55) about a milquetoasty junior-high teacher. The lead is played by Funhouse fave Wally Cox, the man who gave us “Dufo: What a Crazy Guy” and, yes, the voice of Underdog. The box offers the first few months of the program, and thus we’re able to see early TV at its best: staging for the camera, flubbed lines that are “saved” at the last minute, and techniques that were dragged over from radio (including an off-camera “vocal effects” engineer). The program itself is an amiable bit of light comedy with nicely sketched characters: Peepers himself, his erstwhile girlfriend the school nurse, the sputtering older teacher (Marion Lorne, later of Bewitched), and Peepers’ bachelor-on-the-prowl buddy (played by a young and seriously energetic Tony Randall). Peepers may not have provoke the belly laughs that can be found in Sid Caesar’s work from the early years of “vaudeo,” but it truly is a gem in its own right. And I’m glad not to once mention in the episode Wally’s wildly famous NYC roommate, a certain guy named Brando.

776.) As the holiday season hits us straight between the eyes yet again, I feel it is time to return to the venerable institution of the variety show, and when pursuing that topic, what better personage is there to salute than one of our Funhouse all-time, all-time favorites, Sammy Davis Jr. This week’s slice’o Sammy finds the indefatigable, inexhaustible entertainment machine performing for a German audience on a Deustche TV special, circa 1985. The program, directed by a certain “Rainer Kaffka” (I’m not kidding) is a full-dose of Sam on stage, with two elements included purely for his European audience: extended scatting segments — including the nicest variant on his familiar “kon-chiki-kon-kon” and his old singer and movie-star shtick (he notes that he resurrected the latter because the Europeans “remembered” him for it — perhaps it’s because they were still very much aware of who those American celebrities were). Next up it’s Sam in one of his rare appearances on Dean Martin’s variety series. Sam does a solo tune (an emblematic late Sixties classic) and then it’s medley time (Rat Pack minus one). I close out with a short bonus or two, including a seasonal favorite (sans SDJr) and a clip that links Sam to one of the biggest phenomena of the mid-Sixties.

777.) As I often say on the show, I never get tired of certain artists’ work, and one of those people is the late, very great Serge Gainsbourg. So this week I share my latest acquisition concerning Monsieur Gainsbarre, a DVD collection from France that for the first time offers English subtitles for the interviews with Serge that were conducted from the mid-’60s to the early ’80s. He went through a number of changes in his career, and while his music is the single best barometer of where he stood emotionally and intellectually at any given time, the interviews he gave on French television were truly eye-openers. His different faces are here: from an extremely nervous jazz vocalist who was experimenting with African rhythms, to the confident crafter of pop-rock and yé-yé singles, to the master musician creating theme albums that continue to be extremely influential, to the somewhat depressed and haggard older Serge who longs for the pure art of the past. I included some gorgeous and memorably hook-y musical interludes to punctuate this portrait of the brilliant and willfully sleazy genius who was Gainsbourg.

778.) The Funhouse makes another invigorating journey back to the Sixties, the decade that qualifies as the “gift that keeps on giving,” as we keep rediscovering gems from that benighted era. First up is a review of Ken Russell at the BBC, a six-film collection of Russell’s kinetic and wildly inventive early biopics. Russell forged his unique style working on these projects and even today they bristle with a wild energy and betray his pure love for the works of the artists, poets, dancers, and composers depicted. From Russell we move on to another film artist, one who made far fewer films, photographer William Klein. The Delirious Fictions of William Klein box contains his three cartoonlike fantasy films, offering savage spoofs of fashion, politics, the media, and the “model couple.” We finish our journey back to the joyously confused Sixties with a review of the new Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour box, a compendium of the best the era had to offer from a mainstream show that stepped off the ledge, and produced some timeless moments of entertainment and outrage.

779.) If laughter is the universal language, then why do we see so few foreign comedies in this country? Well, without getting into issues of U.S. cultural imperialism and the freakin’ awful remakes of foreign comedies that have appeared in U.S. multiplexes, let me instead note that foreign comedy is always welcome on the Funhouse. This week’s Consumer Guide runs the gamut backwards from broad, broad farce to subtle deadpan humor. First it’s Eagle Shooting Heroes, a Hong Kong Chinese New Year ensemble piece that was a quickly produced farcical counterpart to Wong Kar-Wai’s Ashes of Time, produced by WKW himself. Next up is a classically French sex farce by the severely underrated Bertrand Blier. How Much Do You Love Me? explores whether a man with a heart condition who’s just won the lottery should in fact bring home a luscious Italian hooker to be his wife. Last we turn to the brilliant Aki Kaurismaki, whose “Proletariat Trilogy” has just been released on DVD. The three films study the lives of working-class stiffs as they enjoy their time off (quietly, ever so quietly), get fired, get arrested, or get rolled, all the while looking for a way out of their no-dough predicament. The comic options are all there, and we’re happy to move from locale to locale, never once using the phrase “high concept”….

780.) For Halloween this year I present a re-airing (with digital enhancements, oooh boy) of my 1996 interview with editor and fantasy-fanboy extraordinaire Forrest J. Ackerman. Forry discusses with us the founding with producer James Warren of his legendary fright-film pic and pun-filled monster-movie mag Famous Monsters of Filmland. He also discusses his other long-stemmed vocation as a fan of fantasy fiction and film and stirs the heart of yours truly by talking about the first-ever fan conventions he attended back in the 1930s (with, among others, a young pal name of Bradbury). We also touch upon his side-career making cameos in films made by the former readers of Famous Monsters: John Landis, Joe Dante, and Fred Olen Ray. Forry takes the most joy, however, in telling me about his encounters with the two biggest stars in the monster-movie cosmos, Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, both of whom he met when they were older gents but still working hard in the “picture business.”